By By Susan Phillips

Copyright berkshireeagle

Firehoses send arcs of water onto a flaming barn roof on a freezing winter night.

Automobile glass is scattered like ice crystals on black tarmac, lit up in colored flashes by the rotating emergency lights of ambulances and police cruisers.

Huge trees in full foliage are split in half by the weight of heavy snow laid down by a freak early October blizzard.

Power lines sag dangerously low under the weight of snow from that storm — one that killed five people, including a North Adams State College student electrocuted by a downed live wire.

Those are a few of the vivid images left in my memory, courtesy of the static-laced voices emerging from a radio scanner set to emergency service bands. Those voices formed a background track to the time I spent working in The Berkshire Eagle’s North County bureau in the late 1980s.

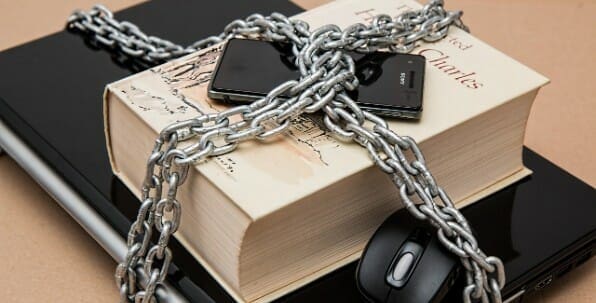

A Sept. 5 Eagle editorial noted that in Boston, public access to real-time information about police activities via radio scanners is threatened by a planned move to encrypted channels. It’s a change that could seriously impair the public’s ability to know what its public servants are doing and when — a problem that will only spread if more departments follow Boston’s lead, here in Berkshire County or elsewhere.

I arrived in North Adams in May 1986 to work as one of three reporters in The Eagle’s Ashland Street office, now a tattoo parlor. My previous experience was as a news writer at WPIX-TV in my hometown of New York. There, we had the scanner on at all hours along with wall-mounted TVs and wire machines churning out news stories from The Associated Press, United Press International and Reuters. It all made for a scrambled wall of sound. As a result, I never listened to it.

But in North Adams, the office scanner was spinning a thread and writing a play in too many acts to count. At night, the story continued at a slower pace, via a second scanner that we reporters would take turns monitoring overnight — one week on, two weeks off.

When it was my turn, the black box would squat on the bedside table in my apartment, intermittently grumbling. I recently asked my husband, who was then my boyfriend, what he remembered about those nights.

“How quickly you got used to it,” he said. “How quickly you could get back to sleep.”

And it was surprisingly easy after the first few nights for me to sense, without fully waking, the difference between a request for someone to do a Dunkin’ run and a newsworthy emergency.

Some things the scanner taught me: Always have gas in the car. Keep waterproof boots and a warm jacket you don’t ever want to wear again in the trunk. Stash a good flashlight and, yes, actual gloves in the glove compartment. Be prepared for the strange privilege of witnessing what could be the worst moments in a stranger’s life.

Eventually, we even had our turn on the other end: “Fire destroys North Adams barn, adding to suspected arson cases,” runs the headline for an Aug. 25, 1988, story by Erik Bruun. “An early morning blaze destroyed a wooden barn at 219 Church St. yesterday, marking the fourth time in two weeks that a vacant building in North County has been damaged by fire … A car, owned by Susan C. Phillips, that was parked next to the barn was badly damaged by heat from the flames. Vinyl on its roof caught fire before firemen arrived.”

Scott and I, who lived on the ground floor of 219 Church, had been roused by the sound of crackling flames. We ran from the house with nothing but our pet cat, Lulu. We watched the firefighters douse the brisky burning car, a rusty blue Dodge Dart that had carried me safely to and from many a scanner-initiated adventure. A day or two later, the faithful beast started right up, and we drove its stinking remains to a wrecking yard.

Through those years, that little black box guided me to rare perspectives of the powerful human qualities that bind communities. I saw the courage of firefighters climbing up to the roof of a burning building and the strength of residents standing outside, checking to see their neighbors were safe, putting on brave faces for their children. I saw the strength of the emergency responders wielding the jaws of life to cut open a crushed automobile and the courage of the injured person trapped inside waiting.

The scanner was the voice of North Adams in my dreams, a mix of doughnuts and disasters, courage and close shaves. My deep affection for the city has its roots there in the voice of the nighttime scanner. And whatever strengths I developed as a reporter reflect the lessons I learned following its narrative threads.