By George Eaton

Copyright newstatesman

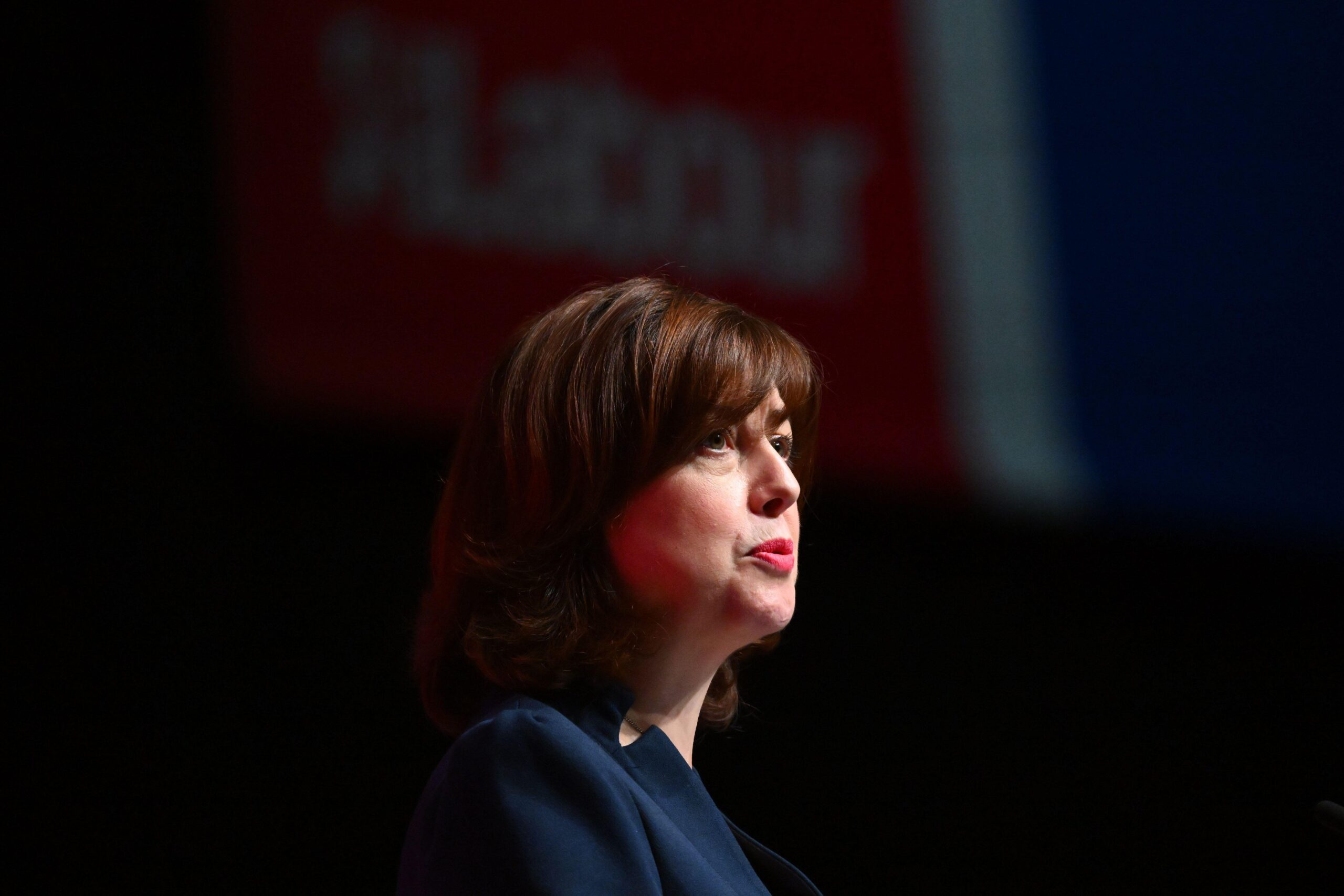

On the afternoon of 5 September Lucy Powell was sat in her Manchester Central constituency office when she received a call from an unknown number. “Oh, this is me about to get the sack,” she told her aides, mindful that a cabinet reshuffle had just begun. Powell was right (it was the No 10 switchboard).

In the ensuing phone conversation with Keir Starmer, Powell asked several times why she had been removed from government, but the Prime Minister “couldn’t really offer a reason; he kept saying, ‘It’s nothing to do with you.’” The former leader of the House of Commons was more disappointed than surprised, believing that she had become “a target” for relaying MPs’ objections to the government’s welfare bill. “It was taken as an act of disloyalty instead of actually trying to help us get through it,” Powell recalls when we meet at a café in Hallé St Peter’s, Manchester, the city where what remains of the Conservative Party has assembled for the week.

She dismisses the suggestion that her comments on grooming gangs during an Any Questions? appearance in May were a factor. “Let’s get that dog whistle out, shall we,” Powell jibed after Reform’s Tim Montgomerie asked whether she had seen a Channel 4 documentary on the subject.

“I got supported by No 10 at the time because I very quickly apologised for that. It wasn’t my intention at all, it wasn’t what I think. It was in the heat of a debate,” Powell says now.

In the days following her departure, she received almost 200 sympathetic messages from colleagues – “really heartfelt, personal ones from people I didn’t realise I’d made such an impact on.” A number suggested that she should stand to succeed Angela Rayner as deputy leader – a prospect that gained wider attention after Andy Burnham named Powell, along with Louise Haigh, as his favoured candidate during a BBC interview. (“I hadn’t spoken to him about that; I didn’t know he was doing that,” she says.)

Due to her sacking, Powell began with no campaign infrastructure: she had no office – soliciting nominations from the den of fellow Manchester MP and sacked whip Jeff Smith – and no staff. But as the candidate of the “soft left”, the wing that so often determines internal contests, she is now the favourite, winning 268 Constituency Labour Party nominations to Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson’s 165, and leading a Survation/LabourList survey of members by 57 per cent to 26 per cent. Though Starmer urged cabinet ministers not to endorse a candidate, two have backed Powell: Ed Miliband, her old boss, and Lisa Nandy (seven cabinet members nominated Phillipson).

Yet there are some in Labour who believe this contest should not be happening at all. Tom Watson, who served as deputy leader from 2015–19, called for the post to be abolished, arguing that it “duplicates authorities and muddies accountability” and “tempts every faction to see a second power base”.

“I’ve spoken to Tom since he wrote that; I’m not sure he thinks that now,” Powell counters when I put this to her, arguing that there is a clear rationale for having a members’ voice at the top of the party. (She has pledged to remain outside government, acting as a “shop steward” for MPs.) Labour activists, she warns, “are quite down at the moment, feeling undervalued and disconnected.”

Phillipson, however, has warned that victory for Powell promises only “more distractions, infighting and noise,” a claim that visibly irks her fellow northerner. “I honestly think it’s just absurd. Firstly, I’m not that kind of person, and that’s not how I have behaved at all.”

“I could have come out swinging three weeks ago last Friday; I absolutely have not. I think it’s quite offensive to members, to be honest. Do you want to debate? Do you want to have a dialogue? Do you want things to improve? The idea that having these thoughts is disloyal misjudges the mood; to be honest, I don’t think that’s gone down all that well.”

Powell attributes Labour’s unpopularity – the party averages just 21 per cent in the polls – to a failure to give “a clear sense of the purpose of this government. Who are we here to serve, and whose side are we on? We’ve been too tactical, tacking one way and then the other, rather than being proactive and agenda-setting.” Though Reform has absorbed much attention, Labour, she warns, is “losing more votes and more support to the left” in the form of the Liberal Democrats and the Greens.

But Powell praises Starmer’s conference speech, regarded by many commentators as the best of his leadership, for giving “a much clearer sense of whose side we are on” and offering the “strong beginnings of an argument about how we need to reshape the economy and the country.”

Notably, Powell believes that her campaign has already moved government policy to the left. “I do, I do actually,” she replies when I ask whether she takes any credit for a new commitment to abolish the two-child benefit cap. “What the last few weeks have shown is that when members’ voices count for something, we shift policy a bit,” Powell argues, sounding rather like Tony Benn, that champion of internal democracy. “And long may that continue.”

Lucy Powell was born in Moss Side, Manchester, on the day of the October 1974 general election (her mother, a headteacher, delayed going into hospital so that she could vote Labour first). Like a number of her former cabinet colleagues, Powell grew up in a tribally Labour household where Margaret Thatcher’s name was anathema. She was delivering leaflets with her social-worker father at the age of eight and joined the party as soon as she was eligible on her 15th birthday. Powell would rush home from school to watch Neil Kinnock, who has endorsed her campaign, face Thatcher at PMQs on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

In contrast to the thriving metropolis of today, the Manchester of the 1980s was, she says, in “complete decline, dying, no opportunities for work”, while her comprehensive was under-resourced and afflicted by recurrent teachers’ strikes. It was this background that drove Powell to fight for change.

Her career is inseparable from Labour and the wider progressive movement: she first worked for the party at Millbank Tower during the 1997 election before becoming a parliamentary assistant to Beverley Hughes MP and campaign director of Britain in Europe, the Europhile pressure group. (Powell says that “as a democrat” she opposes rejoining the EU and praises the government’s new trade deal as “the right approach.”)

In 2010, she ran Ed Miliband’s leadership campaign, later serving as his deputy chief of staff and in his shadow cabinet (as well as Jeremy Corbyn’s) – a soft-left CV that some of her more factional opponents hold against her. “It was always going to be a difficult election for anyone to win,” she argues of the party’s 2015 defeat. “History might end up being kinder on Ed, and he’s shown now how effective he is.”

“Like it or not – and some people don’t like what Ed is doing at all – he’s got a very clear agenda and that makes him effective and I think that’s why he remains very popular, especially in the Labour Party. People know what he stands for and I think that’s something we all should collectively take a leaf out of his book on.”

When I press Powell on her own ideological identity, she opts for generalities: “I hate these sorts of questions. I think I’m just Labour through and through, really; I hate these isms.

“I’m someone who very strongly believes in addressing inequality. I think the growing and deep inequalities in the country are the root cause of a lot of our problems, and that drives me.”

But there is one ism that Powell is prepared to embrace: “Manchesterism”, the label adopted by Burnham in his recent New Statesman interview (north-west MPs, eight of whom lost jobs in the reshuffle, aided Powell’s early advance). “There’s definitely a form of Manchesterism that I would adopt. You can change people’s lives when you have a clear and long-term plan for inclusive growth built on access to good skills, to decent housing and to affordable housing… I think it predates Andy a bit,” she quips.

One claim made repeatedly about Powell during the contest has been that she is a “stalking horse” for Burnham – primed to help ease his path back to Westminster through a seat on Labour’s National Executive Committee (which oversees candidate selections). It’s a charge that Powell, understandably, resents.

“I do think it’s, quite frankly, sexist, to be honest – the idea that, as a woman, I’m not able to stand in my own right, that I’m only standing on behalf of either Ed Miliband or Andy Burnham” (some MPs believe that Miliband could be the soft left’s flagbearer in a future leadership contest).

“Anyone who knows me knows that this completely underestimates me, is sexist, and a bit ridiculous – and that usually it’s me bossing all the men around. I’m sure Ed and Andy would say that to you if they were given the chance.”

Would she like to see Burnham return to parliament?

“That’s entirely up to Andy. I’m not here as his spokesperson or anything. What I would say is that Andy is very effective, very talented, very popular. We see that in Manchester all the time.

“He does reach parts of the country, parts of the electorate that we struggle to reach. We need to embrace Andy and others to really show the best of ourselves collectively. I know that he wants to help do that as well; he needs this government to succeed as much as everyone else does.”

What of Powell’s own future? Though she would be the first deputy leader since George Brown (1960–70) to serve on the backbenches for a sustained period, Powell says that she will decline a government post if offered one by Starmer.

“I’m very clear about the job I want to do, and that’s a job that wouldn’t be confined by collective agreements and the pressures of running a department or being in government.”

But Powell, who reveals that she had a recent conversation with Starmer, adds: “I’d be in the political cabinet, absolutely” (meaning that she would attend cabinet meetings when civil servants are not present). “I’ll be at the top of the party; I’ll be part of lots of formal arrangements, working across government and reconnecting with our movement.”

Some MPs, including former Starmer loyalists, have set an effective deadline of May 2026 for an improvement in Labour’s position, but Powell refuses to be drawn on speculation that the Prime Minister could be challenged.

“I’m not writing off those elections next May. If I’m elected on the 25 October, I’ll be getting to work to do absolutely everything I can to set a different course that can help us do better in those elections than we’re currently on track to do.

“We’ve got thousands of elected representatives facing the ballot box, and they’re really worried about that. So that’s what I’m going to be 100 per cent focused on. I’m not going to be thinking about the aftermath.”

[Further reading: The truth about the small-boats crisis]