By Vivek Menezes

Copyright gqindia

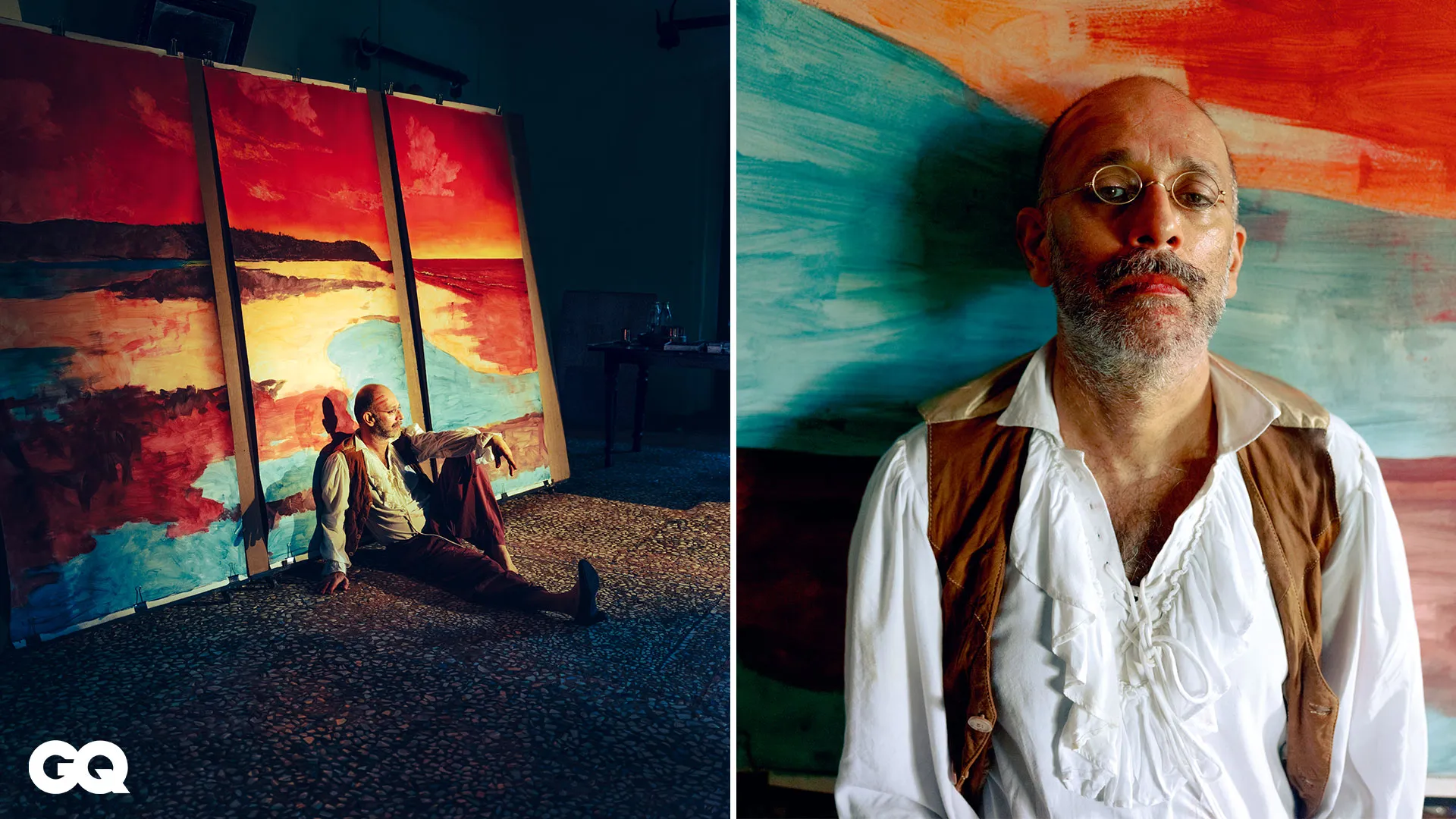

Quitula and Corjuem in Goa are previously unknown names to the international art world, while the plea-santly ramshackle Aldona village market used to be famous mostly for its flavourful local chillies. And though there is indeed a fair amount of rampant real estate development scattered around that is transforming India’s smallest state, you can still wander through this exceptionally bucolic landscape curving alongside the Mapusa river in North Goa, and never suspect that it’s both the laboratory and launching pad for one of the most fascinating artistic developments of the 21st century.

That unlikely happenstance came about because artists Nikhil Chopra and Madhavi Gore chose to transplant themselves here and raise their two children amidst a profusion of friends like family who have together created HH Art Spaces. “An artist-run -movement working with live and performance, -visual, sonic and installation artists locally, -regionally and internationally”, that is set up in an otherwise -nondescript little building adjacent to the marketplace. In just a single decade, they have gone from putting together what felt like homemade art–inflected house parties to global recognition. And now, at a most crucial juncture for the global scene as well as for the troubled Indian art world, HH will curate the sixth edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale.

To be fair, it is not only the Indian art world that is struggling to find meaning at the moment. Recent editions of the world’s biggest art extravaganzas have foundered and failed in notably similar ways: -mismanagement, financial issues, disconnect between social justice themes and their own predatory practices, which have led to artist protests and boycotts, plus thorny geopolitical and ethical tensions (with Gaza paramount). Here, however, the stakes loom even higher because two full generations of Indian artists have found themselves routinely sidelined by the marketplace’s unhealthy obsession with a handful of mid-20th-century “masters”, as the Indian art world has become dominated by individuals with an even unhealthier relationship to state power. A vast dumbing down has resulted, as the big art fairs in New Delhi and Mumbai amply demonstrate. To this vexed scenario, HH brings fresh thinking directly from the Aldona market, with its curatorial note stressing: “An invitation to embrace process as methodology and to place the friendship economies that have long nurtured artist-led initiatives as the very scaffolding of the exhibition. We move away from the idea of the Biennale as a singular, central exhibition event, and instead envision it as a living ecosystem; one where each element shares space, time and resources, and grows in dialogue with each other.”

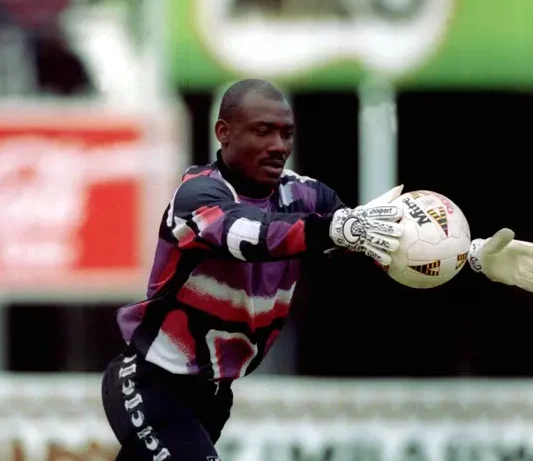

All these ideas are inherent in the HH ethic as it has developed over the past decade, and in many ways, they’re an organic extension of Chopra’s extraordinary art practice. Known widely as one of the pioneers of performance art in India, and mentored in the field by the renowned performance artist Marina Abramović, he has worked in ensembles to present epic works at the world’s greatest venues, such as the Venice Biennale, Documenta, the Yokohama Triennale and the Sharjah Biennial. In 2015, at the Havana Biennial, he lived in a cage in a public plaza for 60 hours, and in 2019—my all-time favourite—he took residence in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for nine days, where he kept wandering its cavernous galleries for a series of profoundly moving engagements.

All along, at every step, elements of the HH team have always surrounded him, and their collective -capacities have grown in tandem. It might, in fact, be Chopra’s greatest achievement, as this bona fide star has highly unusually managed to encourage and nou-rish an atelier of equals. It also bodes very well for what might be possible at Kochi, to leapfrog Indian art out of its entrenched doldrums.

“The decision to move to Goa was not just about finding physical space,” Chopra tells me, gesturing out of his studio window to the paddy fields in the distance. “It was also about escaping the hyper–industrial, hyper-urban cacophony of a city like Mumbai. That environment didn’t allow me the scale or clarity I needed to expand on the ideas I wanted to explore. The original impetus was simply to thrive in my own need to make art freely in a nonjudgmental, open-minded and emancipated environment. And Goa has given me that. It really does set itself apart as one of the last liberal corners left in the subcontinent—a place where there’s still room for dissent, for open conversation and open-mindedness.”

But “what really sits at the core of my practice now, and what drives me in being in Goa, is the ability to build a community around HH Art Spaces. It has -allowed us to bring together young artists and practitioners, to invite partners and collaborators, and to grow—not just individually, but also collectively as an organisation and a community.”

Over the years, I’ve attended several HH events and observed with sheer wonder and delight as they kept on getting better and better, increasingly ambitious and meaningful, with an extensive shape-shifting hive of artists and curators looping in and out of Aldona. By now, I’ve become accustomed to being provoked and pleased by the works being presented, but what really strikes me every single time is how happy -everyone appears to be, both in the limelight and offstage. It is the precise antithesis of what prevails in the rest of the high-end of the Indian art world in our times, as it has become increasingly petty, pretentious and oligarchic. For that reason above all, it strikes me that HH is an inspired choice to host the most important event in the national art calendar. “While we recognise that art alone may not change the world,” the team conti-nues in its curatorial note, “we believe when cultures collide, that encounter can, at the very least, provoke conversations. This constant unsettling can possibly break the static silence, even if temporarily. We believe this is what a Biennale can be: a space of aliveness, presence, and communion.”

It’s a persuasive vision for these precise times, but also something that Chopra and Gore have settled into throughout their lives together, and the way of being for their family. This is again something I have marvelled at for long—having met them for the first time soon after they arrived in Goa—as they were always surrounded by an incredibly tight-knit group of collaborators, including those who literally moved across the country to remain close. When I ask her about it, Gore tells me, “We just drew energy from other couples and individuals who have seemed to survive their individual strength, and they drew from us, too. It’s like mirrors. As a mother of two, being part of a collective moment enabled me to keep working and staying in the loop, and it became important to realise that holding space for each other to grow and develop is the only way forward in a partnership of any kind -because one can’t do it alone. You always need someone holding the fort, someone running the race, someone cleaning up the mess, and someone just waiting for you on the other end in acknowledgement and respect.”

Gore first met Chopra in 1997, just after graduating from St Xavier’s College in Mumbai. “Nikhil had finished BCom the year before and had been encouraged by his father to travel,” she says. “We met for chai at the Sir JJ School of Art campus and then walked around Colaba, going to galleries. He was already familiar with the work of many Indian artists and charmed me with all this information and the clarity that he would make a profession as a painter. I found this a great privilege—to travel and open up your perspective and have the space to understand yourself and grow your individuality to recognise your talents. A calling!”

The two immediately went on the road together, and “somewhere along the journey, experienced so much laughter and fun, it felt free; a Bonny and Clyde sort of spirit,” she says. “We were drawn to each other. We went through college and university together; I suggested going to the USA to study, and he followed. I supported him, sourcing props for his BFA and MFA shows, which were very well received. And continued to do so until his productions got bigger and were -better funded, where he hired designers and photo-graphers, some of whom were old friends of mine, and those working relationships have lasted over 20 years in practice. The family has expanded, and the core has been getting stronger.”

It was at Ohio State University, where Chopra earned his MFA, that another big breakthrough occurred. “Artist Ann Hamilton invited Marina Abramović to participate in a seminar,” he recounts. “Since I was assisting Ann at the time, I had access to Marina—not just as the artist, but also as a person. I had the opportunity to bring her into my studio, to have a critical look at what I do and to have a one-on-one conversation with her. What truly crystallised our relationship, though, was an invitation from one of the leading curators in the world at the time, Hans Ulrich Obrist. He invited me, along with Marina, to be part of the Manchester International Festival back in 2009. I had the opportunity to work alongside her in an immersive setting. As a performer, I was cura-ted to present the rigour of my practice over 18 days, eight hours a day. It was an intense period of close proximity to Marina, who has played a vital role in the history of art, and broke ground and many barriers, especially through her partnership with Ulay. That ethos has shaped my entire body of work and the career I’ve leaned on. That said, I’m not just in awe and reverence of Marina; I also approach her work with a critical lens. But she has unquestionably played a vital role in informing what I believe is possible—and just how far one can go—with the body.”

You can see the impact of this seminal relationship in HH’s curatorial note for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, which says, with great poetic beauty, that “our inquiry begins with the body—chemical, tender, marked by memory and intimacy. We see the body as a landscape of time, a vessel of labour, joy and loss. From these bodies emerge processes that transform into other bodies, extensions of ourselves through which meaning is carried and reality reimagined… This edition of the biennale is also an invitation to think through embodied histories of those that came before us and continue to live within us in the form of cells, stories and techniques.”

At the time of writing, the artist roster for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale was still under embargo, but it is no secret that HH Art Spaces will raise the bar considerably, both in terms of inviting big names to India for the first time and its very wide survey of some of the exciting and unknown younger artists from across the subcontinent. Chopra told me this kind of range is only possible with “many eyes” surveying the possibilities, and another core HH member, Shaira Sequeira Shetty, also emphasises that “we hope to create friendships and relationships that last, and prioritise care over anything else, as we progress towards the Biennale opening. HH has taught me that work without an emotional backbone is very boring. If one cares about something, doing it without emotion is impossible.”

Shetty, who met Chopra and Gore in 2016, says, “My working relationship with Nikhil and Madhavi over the years has been dynamic—from parental, to friendship, to mentorship and guidance. They live all-encompassing lives; it’s the people that they are that I’m drawn to more than the working relationship we share.” That same personal magnetism also drew in Shivani Gupta, a sensitive photographer and artist (she is trained in Mohiniyattam), who documents all of Chopra’s individual projects. “It was love at first sight,” she says, recounting how Chopra and Gore crashed her birthday party in 2005, and “we immediately began jamming. A jam that has lasted 20 years now. I think our work together nurtures our friendship, and the friendship feeds the work. They are my partners, co-curators and my best friends. We haven’t been able to make boundaries.”

Gupta says HH was first initiated by Romain Loustau with Nikhil and Madhavi in 2014, and has grown organically with Shaira, Mario D’Souza, Madhurjya Dey, Divyesh Undaviya, Shruthi Pawels and Alex Xela as integral parts. “We just did not stop growing. Being in HH transforms me, and taking this to Kochi at this scale is very exciting. I feel that we are waking up in a broken world, and our methods are about friendship, respect, empathy and kindness.”

I ask Chopra how he perceived the many-layered curatorial challenge in front of him now, with HH Art Spaces stepping out of its quirky, laid-back -Aldona market setting to the biggest and most important stage in Indian art. He responds remarkably thoughtfully: “The Kochi-Muziris Biennale is, in a sense, in its adolescence. It’s at a point where it really has to understand the position it holds within the context of -contemporary art practice, not just in the subcontinent, but also the role it plays globally. We need to focus on its successes, even as we learn from the stumbles, the speed bumps, the financial issues and the challenges around labour and talent that have emerged over the years. It’s also important to recognise that this Biennale doesn’t aspire to be anything other than itself. It must see itself as an asset—as a generative force, as a place of unique conditions where artists are given the kinds of opportunities they wouldn’t find anywhere else.”

“Nearly 8,00,000 people attend each Kochi-Muziris Biennale,” Chopra explains. “That number is staggering. And 90 per cent of those attendees are local. These are people who are politically aware, who read newspapers, who understand the context. So, the Biennale must not only -understand its own success, but also how to invite the richness of this place into its structure. I don’t think there’s another place in the country where one can engage with the kind of conversations that come out of being in Kerala. We are a resilient people. For generations, we have incorpo-rated internationalism into ourselves. This dialogue that India, and especially Kerala, has had with the world goes back thousands of years. I’m not saying this to pander to the nation or state, but to acknowledge the depth of that history… The world is watching. We have their attention and their curiosity. The question now is: What do we do with it?”