By Dong Lei

Copyright scmp

A young Winston Churchill once warned: “The wars of peoples will be more terrible than those of kings.” In our current moment, this warning feels less like prophecy and more like diagnosis. Across the globe, nationalism is no longer a quiet undercurrent; it is a dominant force shaping identities, policies and personal destinies. And nowhere is this more visible than in the two most influential powers of our time, the United States and China.

In the US, the death of Charlie Kirk, a young conservative, has triggered political and cultural fallout and marks a disturbing milestone. The suspect, even younger than Kirk, represents a generation raised in the digital trenches of ideological warfare. This was not merely a tragic act of violence – it was a rupture in the American psyche. It forces us to confront a deeper question: are we entering an era where the passions of the people, unmoored from institutions, will drive us towards more terrible conflicts than ever?

American nationalism is deeply personal. It is rooted in the mythos of liberty, individualism and moral exceptionalism. From the founding fathers to modern populist movements – and as amplified by Hollywood, mass media and the algorithmic echo chambers of social media platforms – patriotism is often expressed as a belief that one’s values are inseparable from the nation’s destiny.

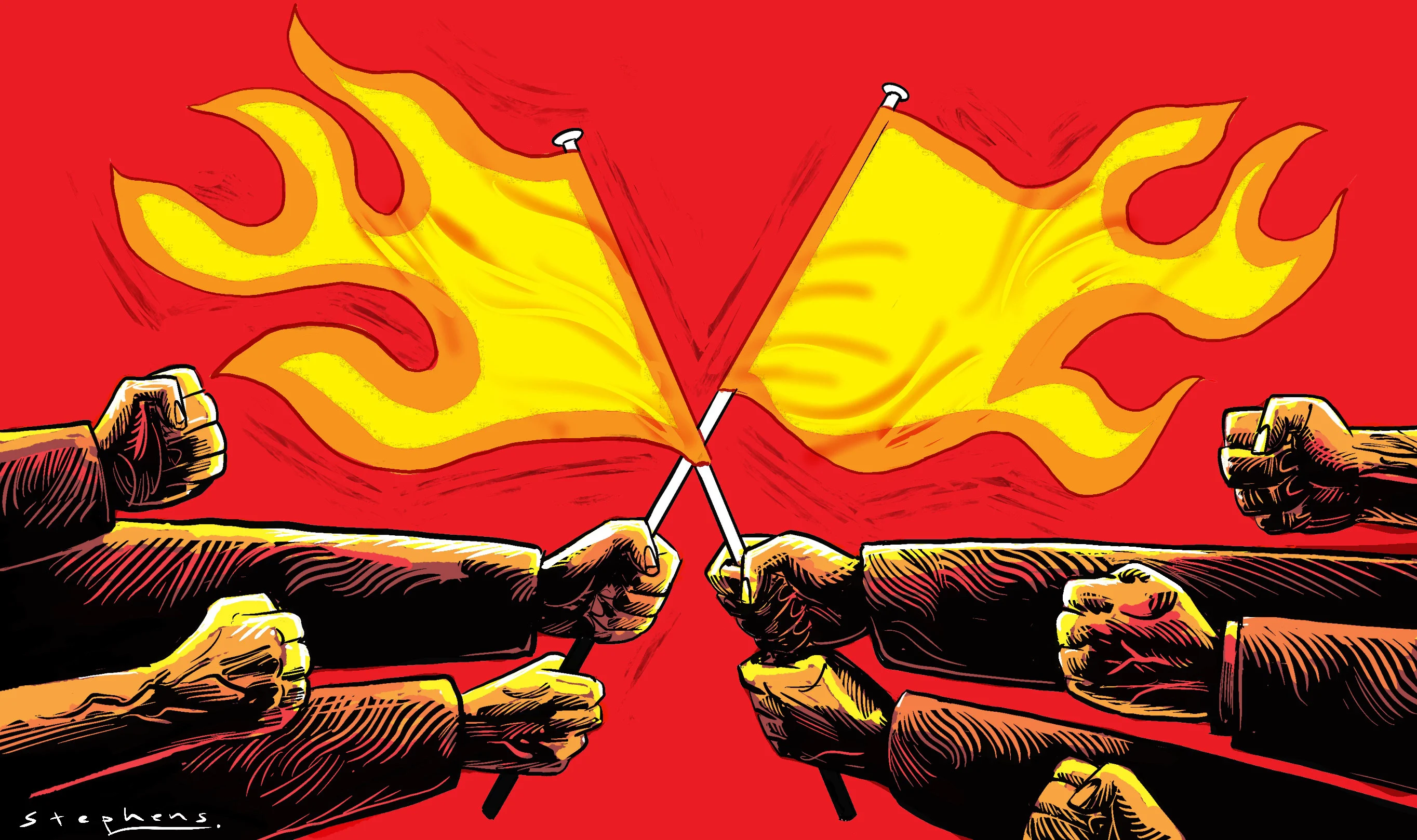

This form of nationalism is volatile. It thrives on personal grievance, elevates the individual to ideological warrior and erodes the space for compromise. The aftermath of Kirk’s assassination – firings, online abuse, even disputes over flag protocol – reveals a society where political identity has become existential. The American flag itself, once a unifying symbol, now serves as a litmus test of allegiance. Similarly, flags have become an issue in the United Kingdom’s summer of discontent.

In contrast, China’s nationalism is more structured and collective. It emphasises unity and shared purpose. Patriotism is a civic responsibility. The national narrative, shaped by historical experience and cultural continuity, encourages alignment with broader societal goals.

This model offers a kind of cohesion that many democracies struggle to maintain. It is strategic, deeply rooted in historical memory and often framed around aspirations for national rejuvenation. Yet beneath this order lies a rigidity that can stifle dissent and suppress pluralism. The Communist Party’s emphasis on harmony often comes at the expense of heterodoxy.

It’s worth recalling that before China’s diplomatic pivot towards the US in the early 1970s, Mao Zedong asked an Australian Communist Party leader about the global youth movements of the late 1960s. Mao’s question reflected a genuine curiosity about the ideological restlessness sweeping across continents. Ever attuned to the pulse of revolutionary energy, he understood that the will of the people was a force that could not be ignored.

Today, President Xi Jinping continues to draw from that legacy, not in imitation, but in strategic continuity. His cautious leadership reflects a deep understanding of China’s historical trajectory and its place in the world.

Both systems in China and the US mobilise emotion. Both create in-groups and out-groups. Both justify action in the name of national interest. But while the US’ model is bottom-up, often chaotic and self-righteous, China’s is top-down, pragmatic and focused on long-term stability.

What’s striking is how these two forms of nationalism, though ideologically distinct, are beginning to mirror each other in their intensity. In both countries, patriotism is no longer a quiet virtue – it is a loud, performative act. And in both, the consequences are growing more severe.

As the two largest powers on Earth, the US and China are not just competing economically or militarily – they are competing narratively. Each offers a vision of what nationalism should look like. And as these visions clash, the rest of the world is caught in the crossfire.

Churchill’s warning was not just about war in the traditional sense. It was about the danger of mass movements driven by passion rather than principle. Today, we see that danger in the streets of America and in the digital spaces where ideology spreads faster than truth.

Across the world, youth are again restless. In Nepal, Gen Z-led protests erupted after a sweeping social media ban, resulting in casualties and the resignation of the prime minister. In Indonesia, young demonstrators forced the removal of cabinet ministers amid growing frustration with entrenched political elites.

And in the UK, a far-right march organised by activist Tommy Robinson drew over 100,000 people, sparking clashes with police and counter-protesters. The rally, framed as a defence of free speech, quickly became a flashpoint for anti-migrant sentiment and nationalist fervour. These events are not isolated – they bear symptoms of a generation demanding relevance, dignity and a future they can shape.

As someone watching from afar, I find myself unsettled. The assassination of Kirk is not just a tragedy; it is a symptom. It reminds us that nationalism, untethered from humility and restraint, can become a force of destruction.

In China, the nationalism I observe is no less powerful, but it operates within a different framework. It leaves little room for chaos and offers a kind of order. Yet even this model must navigate the complexities of modern identity and global perception. The party’s confidence in its narrative is formidable, but confidence without introspection risks calcifying into dogma.

So where does that leave us? Perhaps in a moment of reckoning. The wars of kings were terrible, but they were contained. The wars of people, fuelled by ideology, amplified by technology and unbound by diplomacy, may be far too terrible to leave as an inheritance to our children.