By Nicholas Spiro

Copyright scmp

In Asia’s real estate sector, South Korea is a star performer. In the first half of this year, the region’s fourth-largest economy recorded the second-highest volume of commercial real estate transactions after Japan. Moreover, Seoul experienced the strongest growth in prime residential prices in annualised terms in the second quarter among 46 markets tracked by Knight Frank.

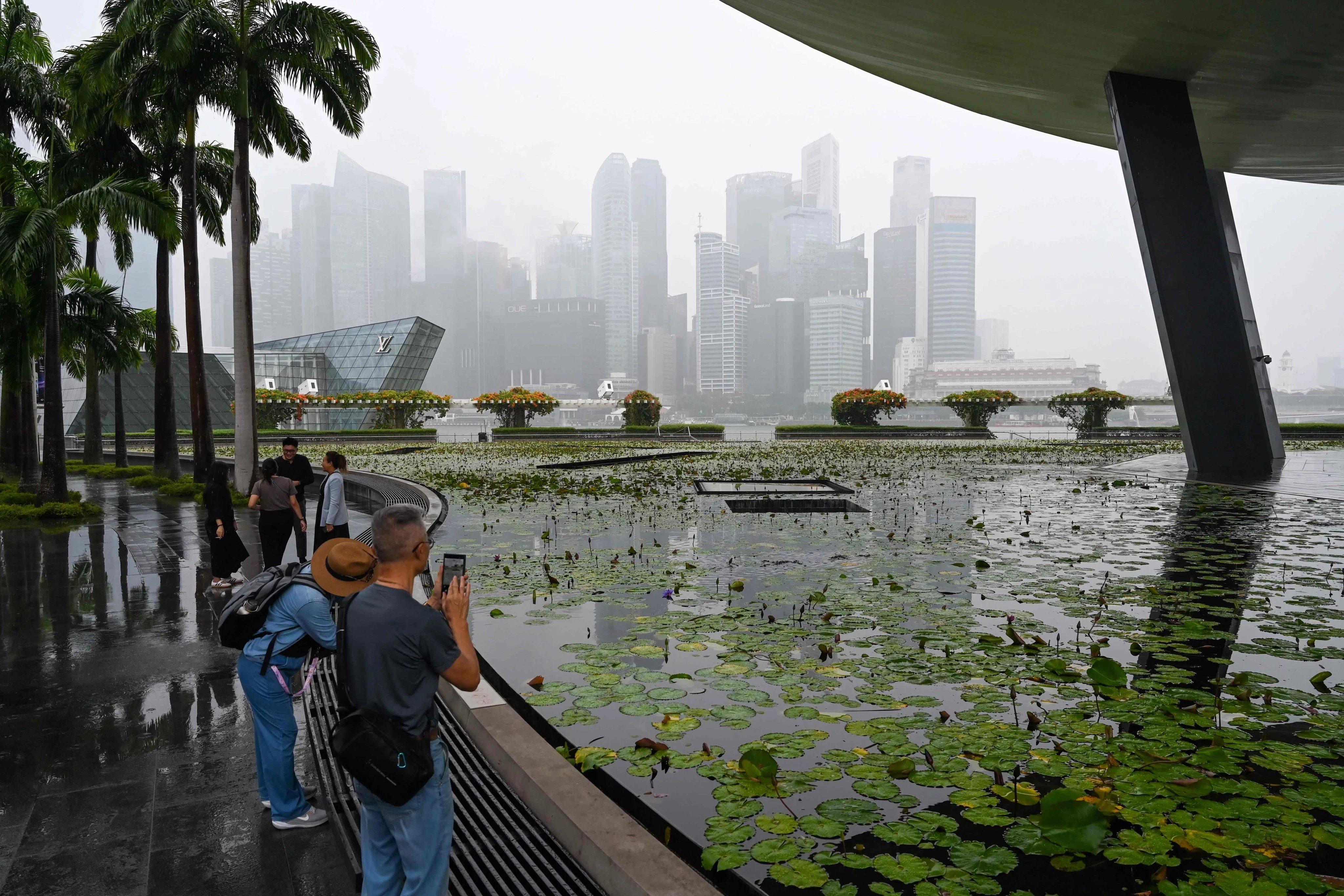

Singapore is another top performer. Office vacancy rates are among the lowest in the region while the city state was one of the top five most actively traded cities in Asia’s commercial property market in 2023 and 2024. In the residential sector, the average price of second-hand private homes rose to a fresh high in the second quarter, while prices in the secondary market of the public housing system have risen for 21 straight months.

In India, one of Asia’s fastest-growing property markets, leasing activity in the office sector in the leading cities hit an all-time high in the first half of this year, while net take-up of industrial and logistics space in 2024 reached its highest level ever, data from JLL shows. In the residential sector, sales exceeded 300,000 units in 2023 and 2024 as demand shifted towards premium and luxury homes in a sign of an increasingly sophisticated market.

However, these top performers are not without their challenges. Housing affordability is a growing source of concern, especially given the failure or ineffectiveness of government policies to tackle the root of the problem.

The South Korean government has sent confusing signals. Last month, it announced a clampdown on foreign homebuyers – who account for a tiny fraction of home purchases – in an effort to dampen speculative demand in Seoul’s buoyant residential market. Then, it announced a lowering of the loan-to-value cap on mortgage loans and pledged to almost double the supply of new homes in the coming years.

The problem is that the price of flats in Seoul has risen despite a succession of measures to take the heat out of the market. Home values in the city have risen for 31 consecutive weeks.

Although the pace of price increases has slowed, a combination of policy flip-flops, overemphasis on demand-side measures and the politicisation of foreign purchases has undermined efforts to improve affordability.

Furthermore, sharp price gains have made it more difficult for the Bank of Korea to conduct monetary policy effectively. Even though the export-reliant economy is more vulnerable to higher tariffs, the central bank opted to leave interest rates on hold last month. With household debt in the second quarter rising at the fastest pace since 2021, fuelled by a surge in mortgage lending, lower borrowing costs risk driving property prices higher.

Policy effectiveness is also a thorny issue in Singapore’s housing market. Seemingly never-ending rounds of cooling measures – such as tighter restrictions on mortgage lending, high taxes and measures to discourage property flipping – have delivered diminishing returns.

Part of the problem is that the government has targeted foreign buyers by increasing the extra stamp duty rate for overseas purchasers buying any property to a staggering 60 per cent. Yet even when the draconian measure was announced in April 2023, non-resident buyers accounted for less than 7 per cent of non-landed private home sales.

In fact, some of the sharpest price increases in the market have been in second-hand flats built by Singapore’s Housing and Development Board, a public agency which houses 80 per cent of Singaporeans, 90 per cent of whom own their flats. While the government has introduced measures to temper demand, it has shied away from tougher curbs because of the political risks in targeting the public housing system.

Moreover, every peak in house prices in the past three decades has been followed by a higher peak, as cooling measures wear off. Even historically cheap districts have witnessed price gains of 40-60 per cent over the past decade. According to Singaporean property editorial platform Stacked Homes, “the escape routes [to sharp price discounts] are disappearing”.

In India, a residential property boom has masked a supply crunch in the more affordable segments of the market. While flats priced under 5 million rupees (US$56,658) accounted for 54 per cent of sales in India’s top cities in the first half of 2018, they comprised just 22 per cent in the first half of 2025, data from Knight Frank shows.

This downturn has contributed to a 13 per cent fall in home sales in India’s seven leading cities in the first half of 2025, the first contraction for the first half of a year since the Covid-19 pandemic, according to JLL.

The shift towards the “premiumisation” of India’s housing market has come at the cost of a growing shortage of affordable homes. Among other factors, the withdrawal of supply- and demand-side incentives has “rendered [affordable housing] financially unviable for developers”, CBRE notes.

For a country experiencing rapid urbanisation and in need of an estimated 30 million affordable homes by 2030, much more should be done to market properties as profitable and attractive for private developers. Moreover, many affordable housing schemes are located on the outskirts of cities where land is cheaper but infrastructure deficits are severe, limiting “the livability and long-term desirability of these projects”. Knight Frank says.

Housing affordability is a universal issue; it has become a more acute concern in the best-performing and most appealing property markets in Asia. This should serve as a warning to policymakers.