If, however, these universities fail to sign on to the government’s meddling in everything from admissions to grading, pricing, hiring, and political expression on campuses, the compact says they are electing to “forego federal benefits.” In other words, they either lose their independence and academic freedom or they lose access to research grants, student loans, federal contracts, visas for their students, and preferential tax treatment.

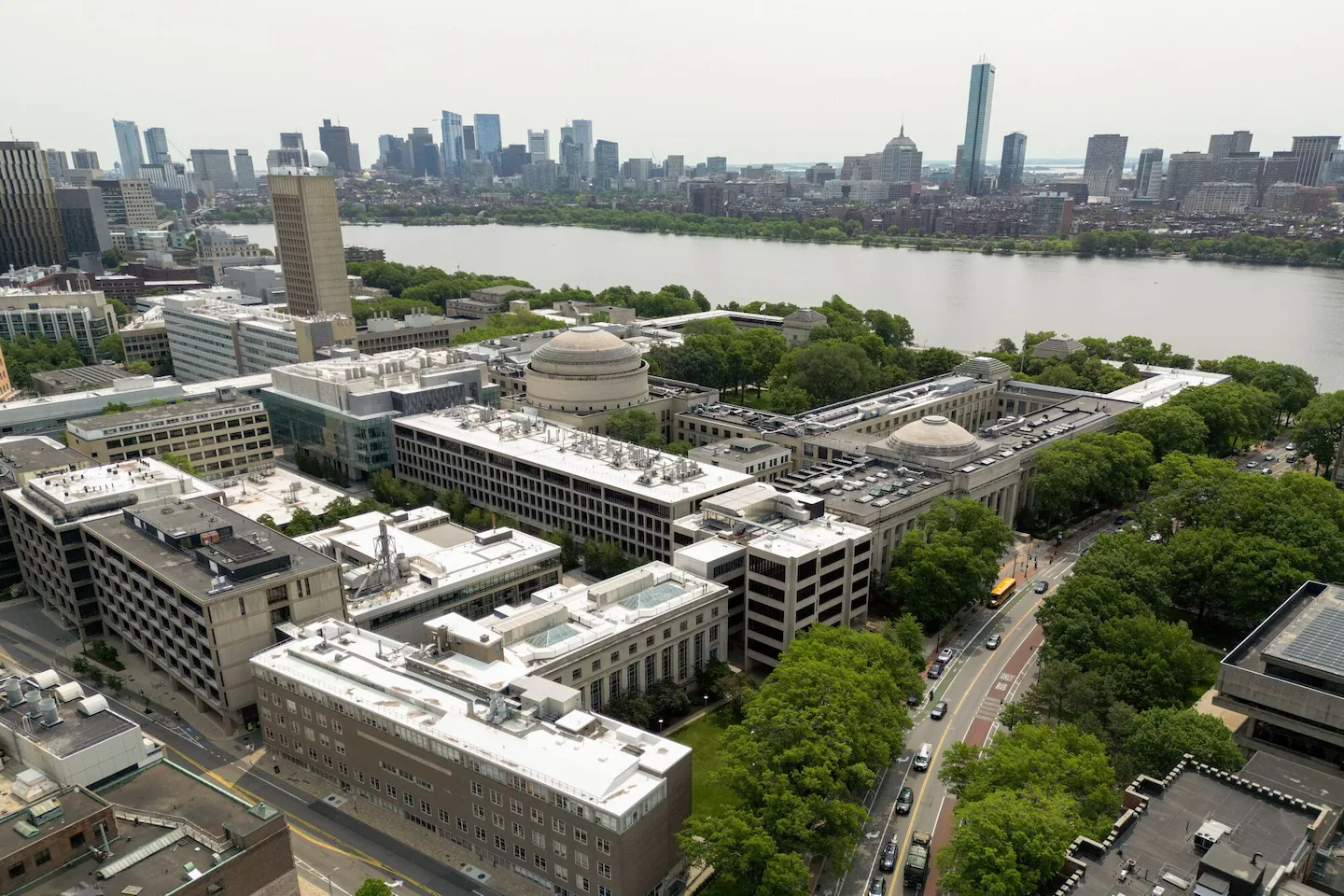

This is the excruciating choice now being faced by MIT, Brown University, Dartmouth University, the University of Arizona, the University of Texas at Austin, Vanderbilt University, the University of Virginia, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Southern California. The goal, clearly, is to completely rewrite these universities’ partnership with the government so they become subjects, not partners, and willing vehicles for conservative ideas.

Speaking for the Trump administration, May Mailman, senior adviser for special projects, expressed the hope that university leaders find the agreement “highly reasonable.” The compact is reasonable only in its tone, not its content. While professing to encourage a marketplace of ideas and to end discrimination of all kinds, the agreement would force universities into “transforming or abolishing” institutional units that “belittle” conservative ideas. Would university faculty no longer be allowed to talk about the science of climate change or vaccines?

While there is much to object to throughout the compact, its provisions on free expression are particularly upsetting. Universities would be forced to audit their students, faculty, and staff for a “broad spectrum of viewpoints” and to make these assessments public. Is “viewpoint” code for party registration? All university employees would have to “abstain from actions or speech relating to societal and political events” in their capacity as university representatives. This seems challenging, in that every university asked to sign the compact has social and political scientists among its faculty. Would professors be allowed to weigh in even on their own areas of expertise?

Most of the university presidents who sign this agreement will sign not because they believe the compact’s provisions are reasonable or necessary. As a group, American universities are widely acknowledged to be the best in the world precisely because they are self-governing. There is nothing that demands the imposition of an array of government-led directives. Legal remedies already exist for the discrimination the compact purports to correct, and universities are already making course corrections. The Supreme Court has already ruled on race-based affirmative action. Do we really need the federal government to go further and to insist that universities only use “objective criteria,” such as SAT scores, to admit students?

Universities that sign the agreement will sign it largely because they feel coerced. Yet they may find that they have given up a great deal for little in return. Enforcement of the compact would be up to the Department of Justice, with no apparent opportunity for an appeal. With a violation, any money advanced to the universities by the government during the year would have to be returned. The punishment does not have to fit the offense. These universities would have to give back not just government funds but also private donations if the donor wanted them back.

Moreover, with this administration, agreements seem to be abandoned and renegotiated on a whim. At the end of July, Brown University agreed to a settlement with the federal government that promised it would be considered for federal funding in the future “without disfavored treatment.” A mere two months later, Brown is among those being threatened with the loss of all federal benefits if it does not adopt the compact’s “models and values.”

I would like to think that I would stand on principle if asked to sign this document, which is unlikely to be the last word in a virulent campaign against higher education by this administration.

On the other hand, university presidents are under tremendous pressure to accept because the administration has a seemingly infinite number of thumbscrews at its disposal and is willing to use all of them to hurt recalcitrant institutions. At Harvard, for example, which has sued the administration, almost every source of revenue has been threatened or successfully cut by the Trump administration, including research funding, student tuition, endowment income, federal student aid, patent licensing, and donor gifts. Even universities with the largest endowments will not survive long if the federal government decides to starve them.

I know where I stand on the question of whether to sign or not to sign. But my certainty is easily won precisely because I am not running any institution. I do not have a board to convince of my position. I do not have faculty who will be angry if I cost them federal research funding or, conversely, if I don’t act honorably in their view. I don’t have alumni and donors on both sides of the issue. I do not have to think about the students who won’t be educated, the ideas that won’t emerge from the university laboratories, or the employees who will no longer have jobs if I don’t take the pragmatic course and pick up the pen.

This is an impossible choice that threatens to destroy one of our greatest assets as a nation — our universities and the brilliant people and ideas they attract and nurture. Any government that asks universities to make that choice is utterly destructive.