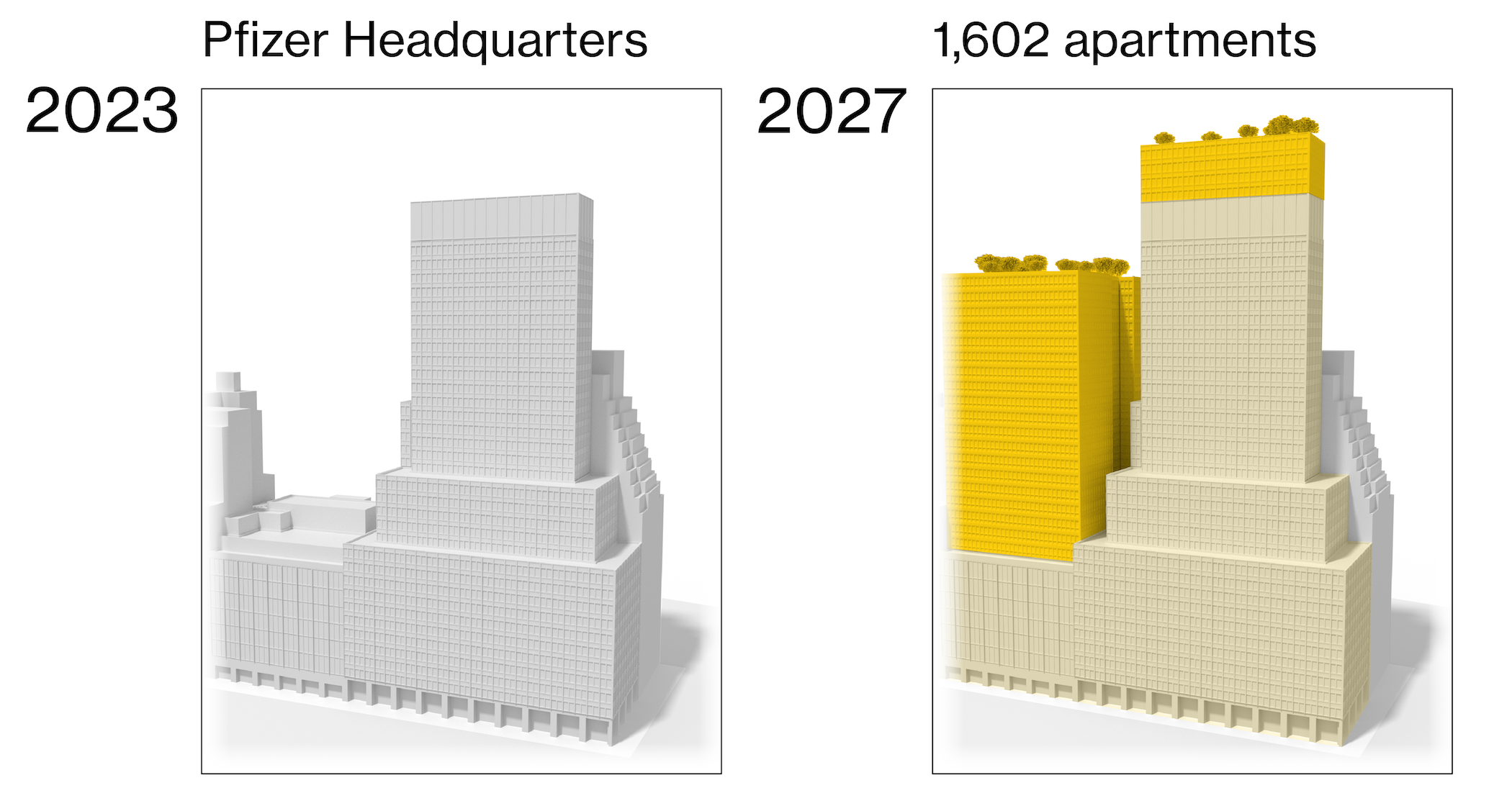

Roughly two blocks from Manhattan’s Grand Central Terminal, construction workers are stripping down the former Pfizer Inc. headquarters to its columns, beams and concrete slabs.

The office towers are expected to be turned into roughly 1,600 rental apartments, rife with amenities such as a rooftop pool and fitness center. For now, contractors are pouring a new floor every four days to try to meet the 2026 opening.

The developers, Metro Loft and David Werner Real Estate Investments, are tackling the biggest office conversion project in the US.

“It’s quite a bit of surgery,” said Robert Fuller, a principal at Gensler, the architectural firm behind the Pfizer conversion. “There’s just a lot of technical challenges and unique conditions from floor to floor. All those things collectively make this quite a unique endeavor and I would argue probably more challenging than any other one I can think of.”

More construction is a welcome relief. Crunched by a housing shortage, the city’s residents are facing rents that are hovering near records and more expensive condos and co-ops. Price pressures have driven politicians including Mayor Eric Adams and Governor Kathy Hochul to greenlight financial incentives and zoning changes that could encourage developers to take the office buildings that emptied out during the pandemic and turn them into more housing.

New York’s housing crisis has also come into stark focus as the city prepares for a heated mayoral election in November. Zohran Mamdani, who won the Democratic primary, has been pushing to freeze rents on the city’s stock of rent-stabilized apartments. That could throw a wrench into developers’ calculations on projects, as many companies are relying on a tax break that requires them to include those types of units in their buildings.

But that incentive — called 467-m — allows for tax abatements for as much as 35 years. In order to qualify for the tax benefits, at least 25% of the housing units have to be affordable. The major benefit of the tax incentive is eliminating some uncertainty around property taxes, according to Nathan Berman, managing principal and founder of Metro Loft, which has done 15 projects downtown.

“Nobody knows where the next administration in the city, where they will be going in terms of taxes, and 467-m eliminates that uncertainty,” he said. “For 35 years — which is huge — you can actually quantify everything.”

Conversions can’t be done to every building. Newer buildings are often tougher to carve into residences. Dividing large office floorplates into individualized apartments and making sure each has access to windows can be tricky. And many buildings still have some office tenants locked in for long leases, complicating any paths to conversion.

The projects aren’t always a perfect balm for New York City’s affordability squeeze either. While a portion of the apartments are affordable, market-rate rents have been on the rise. In August, Manhattan’s median rental price for new leases was $4,600, up 8.4% from a year earlier, according to appraiser Miller Samuel Inc. and brokerage Douglas Elliman.

Despite these obstacles, conversions are booming and helping to repurpose swaths of empty office space that popped up more during the pandemic. The rise in remote work caused some employers to back off on their real estate footprints, while tenants also started preferring new or renovated buildings with top amenities to lure employees back.

Shifting demand, combined with higher interest rates, has been weighing on office prices, making many buildings cheaper. Since December 2019, a measure of US office prices has slumped nearly 11% through August, according to MSCI Inc. data.

“Midtown is heating up,” said Doug Middleton, a CBRE broker that has worked on several conversion deals. “It’s probably the most competitive product that we’re seeing in New York City right now.”

Demand for office space has started to rebalance slightly in recent months, but US landlords are still struggling with a vacancy rate that was about 23% at the end of the second quarter, according to Jones Lang LaSalle Inc.

Five years after the pandemic’s start, conversions are starting to have an impact. The pipeline of those projects totaled 81 million square feet (7.5 million square meters) as of May 2025, up from 71 million square feet just six months ago, according to CBRE Group Inc.

And in New York City, the projects are shifting northward. Decades ago, developers set their sights on towers in the Financial District, also known as FiDi. Art Deco- or Gothic Revival-style buildings offered an attractive conversion opportunity, with historic facades and smaller floorplates that were easier to divide and let in more light. An array of financial incentives in the 1990s and zoning changes lured developers to those buildings.

The area around Wall Street was also stuck with more empty offices after the early 1990s recession, the Sept. 11 attacks and the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 pushed companies to seek out new spots further north in Manhattan. That resulted in cheap, vacant commercial buildings downtown that were easier to revamp.

But since the pandemic, developers converting old office towers started moving uptown as well. As of early September, there are 12.4 million square feet of conversion projects underway or planned in Manhattan — equivalent to more than four Empire State buildings, according to CBRE Group Inc. About half of those are located in Midtown.

On an August afternoon, Metro Loft’s Berman is standing on a platform extension some 250 feet above ground level. He’s overlooking the more than 200 workers toiling away at the Midtown site.

A light well stands between the two buildings, located at 219 and 235 E. 42nd St., helping to illuminate apartments in the core of the towers. The lobby had been stripped down to steel beams. The black marble floor, which will be replaced with new stone, was caked in a heavy layer of dust.

On the 23rd floor, a robot has drawn an outline on the concrete for the 16 studio- and one-bedroom units that will be built there. The original tinted windows, still in place, will be ripped out and replaced with more energy-efficient ones. Of the roughly 1,600 apartments in the completed building, about 400 of those will be considered affordable and rent-stabilized.

One of the alluring parts of conversions for cities and residents is the speed in which the buildings can turn into housing sooner than ground-up construction. Metro Loft’s Berman has said that converting an old building is typically less expensive than starting from scratch — partially because of the quicker time to get construction going and secure approvals.

“That’s what makes conversions exciting for us — the immediacy of it,” Berman said during a tour of the construction site. “You buy a building and maybe 18 months later, you’re renting apartments. That type of schedule doesn’t exist for ground up. You’re lucky if it’s year seven that you rent it.”

Why Midtown

For years, the bulk of the projects were concentrated in downtown in part because the buildings are often older in that area. In general, the city limited Midtown conversion projects to buildings that were built before December 1961, and before January 1977 for properties in the Financial District. But regulations have loosened in the past year, making it easier for developers to target newer properties.

A weak office market has helped as well. Elevated interest rates, and demand pressures from the rise in remote work, have weighed on the valuations of office buildings. At the former Pfizer headquarters, Metro Loft’s Berman saw a chance to finally make his mark on Midtown — a feat made possible by the plummeting valuations.

“It’s literally a neighborhood within the shell of a building,” said Berman. “With all the low-rise products in some of these other neighborhoods, you would need to literally take multiple blocks to get the amount of people that we’re going to have living in here.”

Across Midtown, developers are taking offices that once housed Ernst & Young’s headquarters and turning those into housing. Developer Vanbarton Group is revamping the longtime home of the Archdiocese of New York into apartments in a project that is expected to cost about $340 million for acquiring and converting the building, Bloomberg News previously reported.

At 750 Third Ave., SL Green Realty Corp. is turning a 35-story tower built in the 1950s into more than 600 apartments. And on Billionaires’ Row near Central Park, TF Cornerstone is converting an office tower into 350 apartments.

The slate of projects is finally starting to chip away at the amount of office space for rent. Since 2023, Manhattan’s office supply has fallen nearly 2% to 416 million square feet, according to CBRE.

New York has vaulted to the top of lists for office conversions, outpacing cities including Chicago and Washington. Part of that is because Manhattan is simply the largest office market in the country, which leads to more buildings that can be converted. Developers have been more attracted to conversions given the distress in the office market and New York’s housing shortage and elevated rents. Plus, the city and state’s incentives have helped with the economics of projects.

“Conversions help us solve two pressing problems: A housing crisis with skyrocketing rents because we have too few homes and older office buildings that in some cases are struggling to attract tenants,” said Dan Garodnick, the chair of the New York City Planning Commission.

Metro Loft’s Berman has worked on conversions around the city. He recently worked to turn JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s former back offices into more than 1,300 apartments downtown — the most complicated one he’s done yet. That deal required cutting two light wells in the middle of the tower to allow for proper light and air.

Leasing began this year, and demand has been high — tenants were especially drawn to the 100,000 square feet of amenities that included a gym, spa and pickleball courts.

The size of the Pfizer conversion “allows us to provide the kind of amenity packages that smaller buildings simply can’t afford to offer and it distinguishes these types of projects from a lot of the smaller boutiquey buildings,” Berman said.

Zoning Rules

State and local lawmakers have introduced more incentives over the years that have helped ease some of the challenges faced by developers wanting to revamp the buildings. Late last year, Mayor Eric Adams passed a plan that’s expected to help create as many as 82,000 housing units over the next 15 years. He also oversaw a program that helps accelerate office-to-residential conversions, whose pipeline includes projects like the conversion of the former Ernst & Young headquarters at 5 Times Square.

As part of that, the city lowered the age of buildings that could be converted and expanded the locations where properties were eligible. The state also lifted a cap that restricted the density of a building, allowing for much bigger developments. Most recently, in August, the city passed zoning changes that would affect an area of Manhattan known as Midtown South. Now developers can build residential properties there, which could result in more than 9,500 homes.

On the conversion of the Archdiocese, developer Vanbarton said that with the 467-m tax incentive, property taxes will cost only about 3% of the building’s effective gross income, compared with roughly 25% without.

“You’ve solved your real estate tax issue and uncertainty for 35 years – there’s a price to pay for that, and it works,” Berman said. “The city is getting much-needed affordable units, which otherwise would just not be produced.”

Midtown Future

To look at the potential impact of conversions in Midtown, New Yorkers don’t have to venture far. Lower Manhattan, the section of the borough that’s south of Chambers Street, has turned more than 26 million square feet of offices into housing since 1995, according to the Alliance for Downtown New York, a nonprofit group that handles the business improvement district in the area.

Major projects continue to open up in that section of Manhattan. Renters started to move into Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s former offices at 55 Broad St. last year. And Metro Loft has started demolition at 111 Wall St. to build more than 1,500 apartments.

“Office to residential conversions are a win-win here: they offer some relief to struggling commercial real estate, they create much needed new housing and they help us create more vibrant 24/7 neighborhoods in our central business district,” Garodnick said.

The office market has started to recover too. In Manhattan, new office leasing in the first eight months of this year was up 38% from a year ago, according to CBRE. The vacancy rate in August was down to about 14% from roughly 16% at the start of 2024.

But there’s still a vast amount of unused space that some developers and lawmakers argue could be put to better use. According to CBRE, if all of the planned and rumored conversion projects were to be completed, it would eliminate another 21 million square feet of offices, a 7% reduction from 2023.

“We’re taking the limping office buildings off the market,” Berman said.