Picture Vincent Van Gogh’s fiery swirls, enchanting olive groves and blazing stars leaping off the canvas, like the artist himself must have seen them.

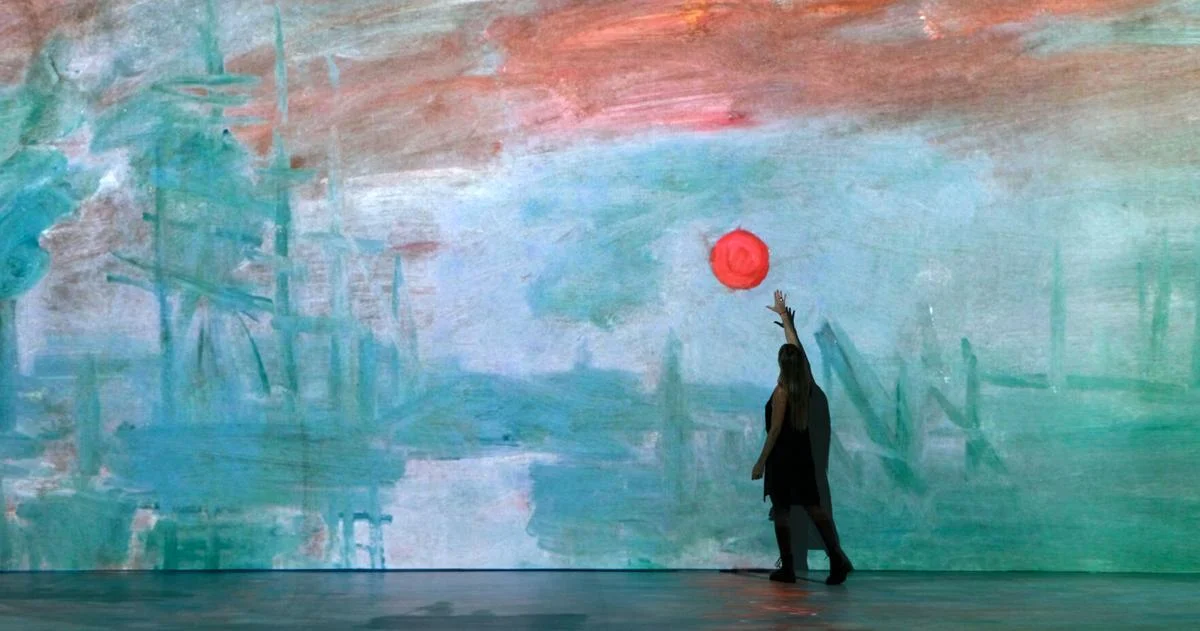

Watch Claud Monet create water that flows, crashes onto a rocky shore or lies tranquil in a pond of lilies.

“Beyond Monet, Beyond Van Gogh” is a popular exhibit that spent the summer in Charleston. The exhibit animates the paintings of the two artists and gives them vibrancy on a panoramic, illuminated screen, infusing in them the “beyond” of movement and spellbinding transfiguration.

Van Gogh never had a chance to grow old; he died at 37. But Monet lived almost 87 years. As he aged, the painter developed cataracts that seriously affected his vision. And for years he refused to have them surgically removed.

In a 46-line poem, German-American poet Lisel Mueller imagines Monet explaining to the doctor his reasons for refusing the cataract surgery. The doctor sees age-related deterioration in eyesight as a real but correctable flaw. But what Monet sees is the maturing of his life’s work: a different way of seeing and of painting that corrects youthful errors of vision.

No longer seeing a world of separate, distinct objects, now he sees things flowing into each other, belonging to each other, often sparkling with dancing light. His “failing” eyesight allows him to visualize the world with softer eyes that perceive unfamiliar qualities containing a new language of light and spirit.

Mueller’s Monet speaks:

Doctor, you say there are no haloes

around the streetlights in Paris

and what I see is an aberration

caused by old age, an affliction.

I tell you it has taken me all my life

to arrive at the vision of gas lamps as angels,

to soften and blur and finally banish

the edges you regret I don’t see,

to learn that the line I called the horizon

does not exist and sky and water,

so long apart, are the same state of being.

The artist “hallows his diminishment” as a gift of mature age, the gift of priceless insight.

He continues: “I will not return to a universe / of objects that don’t know each other. . . . The world / is flux, and light becomes what it touches, / becomes water, lilies on water.”

We don’t know in words what Monet himself felt about his changing vision. But we have his paintings, and in those we see discreet things spilling into each other, we hear them speaking in a non-literal, non-“knowing” voice that doesn’t fully reveal what the painting portrays. Not breaking things down and analyzing them, but becoming aware of their “strange entanglements” as quantum physics was beginning to do when Monet died in 1926.

As his eyesight diminished, Monet’s vision outgrew what he called, in Mueller’s poem, “my youthful errors: fixed notions of top and bottom, the illusion of three-dimensional space, wisteria separate from the bridge it covers.”

Now he was improvising at the frontier of the unknown.

The traveling exhibition “Beyond Monet,” along with Mueller’s poem, put the inevitable physical changes of age in a different light for me. Like many in my age cohort, I’ve had cataracts removed from both eyes. I wear hearing aids, have one artificial knee and a partial bridge. My list goes on of age malfunctions mitigated so as to keep going.

I’m no Claude Monet refusing cataract surgery. So my dialogue with him is not just pleasant chit-chat. What he says to me — through his paintings, through clues in Mueller’s poem — is direct and confrontive. It goes something like this:

“Everything depends on what you make of the changes happening in your body,” I hear him say. “Think: as you’ve increased in years, have you learned the secret of letting go? Are you able to let go of things, abilities, fixed ideas, even a worn-out self-concept? Are you able to see letting go as falling upward into a new reality?

“When you were a child,” Monet continues, “every childhood day was a school for adding on knowledge about the outer world. And you added on abilities too: you could do more and better as you grew. Now don’t you get it that old age is a school for letting go? Life balances out that way! Are you letting go knowledge about the outer world and making room for insight into what’s beyond it, within it? Within yourself?”

My inner Monet won’t let up. “In the school of letting go, where maturity teaches you not how to keep adding on but how to consent to taking away, have you discovered yet that the love that continues to pulse in you changes—from possessive love, the love that binds things and people to yourself, to a letting-go love, content in things just being what and who they are? And have you discovered that this kind of love you’re growing into is more real than the hungry passions of younger years, less complicated and maybe even happier?”

That was Monet speaking frankly about reframing losses that accompany age. My own reframe still leaves room to seek aids and replacements when they’re possible and maintain the highest level of health I can. But what is equally important, Monet calls me to have the courage to let go of what’s past its time in my life. Something new is waiting.

In Lisel Mueller’s poem, Monet brings his meeting with his doctor to a close with a wish that could embrace all of us who are aging. Call it vision with heart:

Doctor, if only you could see

how heaven pulls earth into its arms

and how infinitely the heart expands

to claim this world, blue vapor without end.