By Srinivasan Ramani

Copyright thehindu

As one travels from the east of Bihar to the centre alongside the mighty Ganges, the warp and weft of people’s dependence on the river is fully visible. The river’s omnipresence expresses the fertility of the soil and the agrarian nature of Bihar’s economy; its wrath reveals the undulating nature of the flood economy and its impact on its people; and the structures built over it point to the human effort to overcome constraints on travel and commerce.

This duality is starkly visible as one enters Bhagalpur, the third-largest city in Bihar. Through the well-laid highways and roads, most of which were constructed recently, a contrast is immediately apparent. The robust roads reflect the investments made in infrastructure in a State where such facilities were relatively backward barely a decade ago, while the flooded waters and fields that abut these very roads reveal the fragility of an economy dependent largely on agriculture.

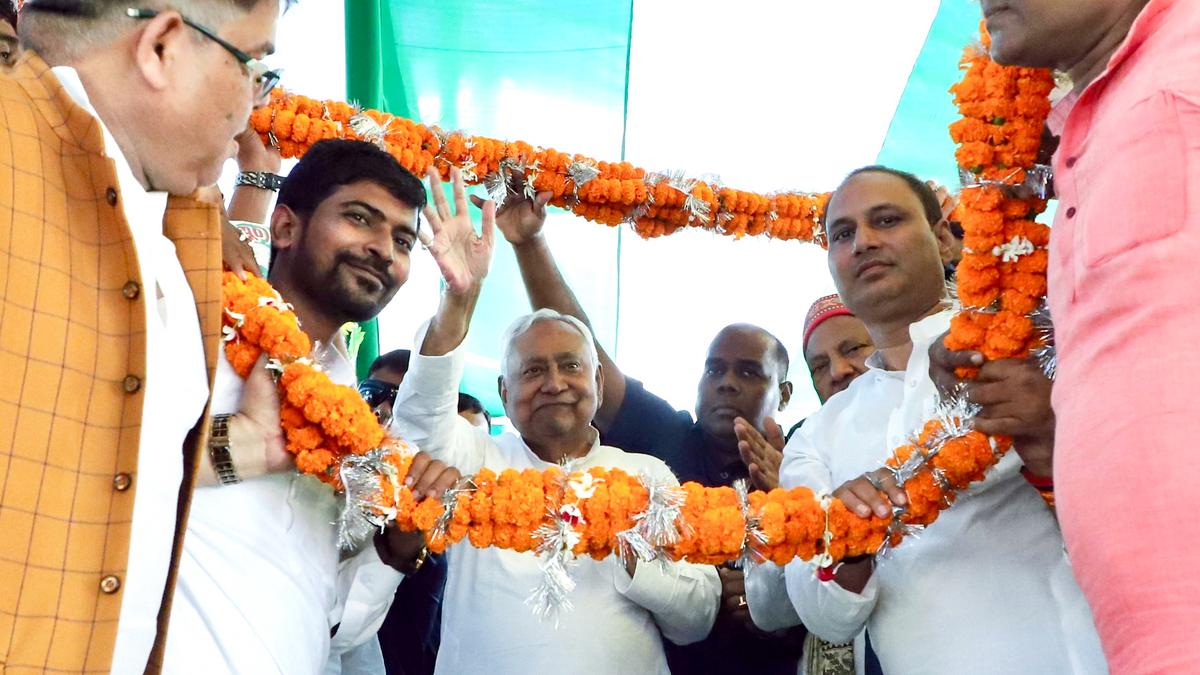

Both these scenes — the life-giving yet destructive river and the smooth roads flanked by flooded fields — serve as potent metaphors for the governance of Nitish Kumar. Having served as Chief Minister of the State for nearly 20 years since 2005, with only a brief interruption, the long-time “socialist” leader remains the talking point in every conversation with passers-by, small traders, and daily labourers.

For and against Nitish

To his supporters in urban Bhagalpur, Mr. Kumar is the symbol of good roads, connectivity, and possibilities of a developing Bihar. These supporters also include BJP members who acknowledge the importance of having Mr. Kumar at the helm. Many belonging to the savarna jaatis, or the upper castes, especially the middle-aged, point to the inevitability of their support for Mr. Kumar, whom they see as a bulwark against the return of Yadav hegemony. Even as they acknowledge the preponderant corruption in public life that affects every citizen, they continue to back him.

However, young and educated youth across sections often differ. The daunting prospects of migration and the lack of economic opportunities weigh heavily on them. There are some who support change, suggesting that Rashtriya Janata Dal leader Tejashwi Yadav has better ideas for employment generation, but these are mostly politically sensitised youngsters or activists. Among the weaker sections, disillusioned youth who had voted for Mr. Kumar in the past — and had benefited from his government’s welfare measures — now look to Prashant Kishore’s Jan Suraaj Party as an alternative (some see it as a long-term choice) rather than the Mahagathbandhan (grand alliance). This search for a third option highlights a potential failing of the RJD: its inability to reach out effectively beyond its core voter segments of Yadavs and Muslims.

This complex voter calculus comes to life at the grassroots level. From the Naugachhia “zero point,” a boat carried a large number of passengers on the Ganges backwaters, who disembarked at what seemed like an unscheduled but regular stop. These were workers coming over to Bhagalpur for their mazdoori (labour). Many of these workers belong to caste categories cumulatively called the “Extremely Backward Classes” (EBCs), who have been a backbone for Mr. Kumar and his Janata Dal (United).

Pankaj, a doctor who runs a joint clinic, is from the Dhanuk community, an EBC group traditionally associated with agricultural work. He offers a detailed case for the community’s longstanding support for Mr. Kumar. He talks about how it was once difficult for them to travel for work, how their lives were perennially affected by flood cycles, and how education and good infrastructure have afforded them mobility in the Nitish years. He asserts that the critique of the Chief Minister — that he has become old and erratic — is made only by political detractors. According to him, the public continues to associate Mr. Kumar with welfarism and development, even if there have been limits. However, he concedes that the lack of better jobs, especially among the educated in his community, has led to murmurs of discontent even among the EBCs. But they do not yet consider the grand alliance a viable alternative, he says.

If the grand alliance assumed that Mr. Kumar’s coalition of communities was fraying, that sentiment wasn’t palpable on the ground. To find signs of a more potent challenge to this dynamic, one must travel further west along the Ganga to Begusarai. In what used to be a stronghold for the Communist Party of India, a keener contest between the National Democratic Alliance and the Mahagathbandhan is visible. In 2020, the Assembly constituencies in the district were split 4-3 in favour of the Mahagathbandhan (the CPI, RJD and the BJP won two seats each and the JD(U) one).

Battleground Begusarai

Here, the Opposition’s ground game is more apparent. Shailendra, a leftist activist in the village of Bihat, meticulously collated anomalies in the Special Intensive Revision’s draft electoral roll, and found that in a specific section of the voter roll for his village, dozens of deceased people were still listed while eligible electors were left out. Helped by Congress activists associated with youth leader Kanhaiya Kumar, the final roll was corrected – 49 people were added and 79 were deleted from the polling booth’s draft roll, a significant change that might not have been possible otherwise. The CPI’s legacy is evident here; Renu Devi, whose name was initially left out, says her allegiance is firmly with the “corn and sickle”.

But even as the SIR, the objections raised to it and the Voter Adhikar Yatra made a mark initially, there is a counter-narrative that has now been woven by Mr. Kumar’s flagship programmes. Those affiliated with Jeevika – his flagship programme for women’s upliftment – say the scheme to transfer ₹10,000 to women’s accounts is a major relief, welcomed overwhelmingly by the poor. The Chief Minister has also mentioned that after evaluating the scheme’s performance, an additional ₹2 lakh as grant will be given to women entrepreneurs after six months.

Indeed, a day after the government transferred the amount to 25 lakh women, bank ATMs and Aadhaar service kendras were crowded. Irrespective of their beneficiary status, women were reluctant to share their political views, a general feature of rural Bihar. However, vocal opposition to the regime was rare, found only among those already mobilised by Opposition activists.

Activists affiliated with the Congress and the CPI admit their parties have declined in their former bases. Young activists Rishabh, a B.Ed. graduate-trainee, and Arshad, a mechanical engineer, both said that Begusarai is no longer the “mini-Moscow” it once was. The BJP has made dents using Hindutva — especially in mobilising Dalits against Muslims in the area — but the socio-economic woes of the educated youth and the poor are no different from those across the State. But they expressed confidence that if the Mahagathbandhan manages and coordinates its campaign well, they could give the formidable NDA a tough fight.

As the election season commences, the political landscape of Bihar reflects the rivers that define it. At first glance, the NDA alliance, steered by Mr. Kumar, appears as the river’s main channel — broad and seemingly unstoppable. But in the deltas and backwaters, in the villages of Begusarai and among Bhagalpur’s restless youth, streams of dissent are forming – though many voters, still waiting for candidate announcements, are yet to choose which current to follow. The coming weeks will determine whether they remain scattered tributaries, or merge into a flood powerful enough to reshape the terrain.