COLUMBUS, Ohio – Just over one in four Ohio students were chronically absent during the last school year. That’s about twice what the state is aiming for, and only down 0.5% from the previous year.

A student is chronically absent when they miss at least 10% of class time a year, at least two days a month. Excused and unexcused absences, as well as suspensions, all count toward the chronic absence total.

At least one education expert suggests it’s time for the state to get tougher on the issue.

Ohio’s rate for chronically absent students was 25.1% for the 2024-2025 school year, according to the recently released Ohio school and district report cards. The figure was 25.6% the prior year.

The state’s target rate is 12.8% — a tall order, considering pre-pandemic absenteeism levels were mostly above that and have remained high since the pandemic.

“It’s a big goal and it’s going to take a lot of work,” said Jessica Horowitz-Moore, chief of student and academic supports at the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce.

Horowitz-Moore noted a change in state truancy law, a planned public information campaign and other efforts may push the rate downward in coming years.

But an education think tank researcher noted that while Ohio gives carrots to encourage attendance, it may be time to also carry a stick.

“We’re doing a lot of the right things, yet our numbers are not changing appreciably,” said Chad Aldis, vice president for Ohio policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a research group and charter school sponsor.

Chronic absenteeism is linked to graduation rates, strong reading skills, and college- and career-readiness metrics. Missed class time isn’t always easily made up. When students are gone, they are missing foundational skills and advanced skills, Horowitz-Moore said.

“Each day matters,” she said.

Research shows that students who are never chronically absent are three times more likely to be proficient in English language arts. In math, they’re 3.9 times more likely to be proficient, she said.

The reasons students are chronically absent vary by family and school district.

High school and kindergarten students have the highest rates of chronic absenteeism. It’s more common in large urban districts and among children experiencing homelessness or other economic disadvantages.

Chronic absenteeism also runs higher in students with special education plans, state data show.

By the numbers

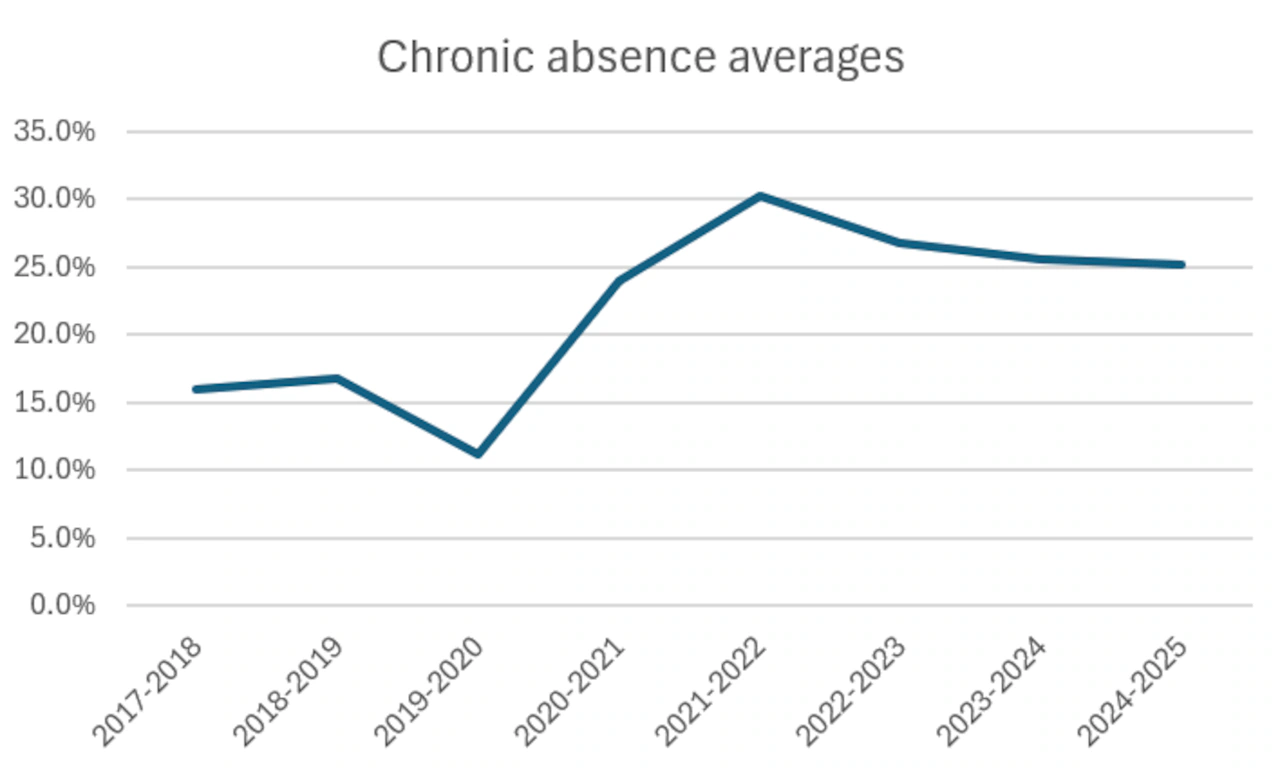

Ohio has had relatively high chronic absenteeism rates for the past eight years, according to DEW data:

-2017-2018: 15.9%

– 2018-2019: 16.7%

-2019-2020: 11.2%

-2020-2021: 24%

-2021-2022: 30.2%

-2022-2023: 26.8%

-2023-2024: 25.6%

-2024-2025: 25.1%

“Before the pandemic we were already looking at chronic absence. We were at 15-16%, and we wanted to get it lower then,” said Horowitz-Moore.

The state does not want students and families to get too comfortable with high levels of absenteeism, Horowitz-Moore said.

“It’s not an acceptable number,” she said. “We don’t want this to become the new normal.”

Affected grade levels

Perhaps unsurprisingly, high schools have among the highest levels of students who are chronically absent.

In 2024-2025, high schools registered the following levels of chronic absenteeism:

-Seniors: 35.9%

-Juniors: 35.0%

-Sophomores: 31.8%

-Freshmen: 31.1%

Among the younger grades, 24.9% of kindergarteners were chronically absent last school year, down from a high of 31.6% in the 2021-2022 school year.

While high school students can leave campus on foot or in a car, parents decide when a kindergartner isn’t going to school, Horowitz-Moore said.

“There’s the misconceptions that parents may have about a kindergartener,” she said. “Parents think, well it’s not a big deal if my kindergartner misses every couple days I’ve got off work. They don’t need to go. Well, yes, they do, because there’s a lot more that we’re doing in those younger grades now.”

Aldis said that it’s more complicated to keep high schoolers in class, and perhaps it’s a matter of engagement. Students may crave different programs or work-based learning, he said.

Or maybe that’s when a stick needs to be used.

“High school students also want certain things,” he said. “They want the driver’s license. That could be a factor in chronic absenteeism? They want to graduate. Is that a factor? We need to be creative about ways of truly incentivizing them being in school.”

A change in the law

In the budget lawmakers passed this summer, the attendance law changed for school districts and charter schools. Schools previously sent letters to families after students missed a certain number of days. That’s been replaced with a requirement to create an attendance plan, Horowitz-Moore said. Local school districts must have an attendance policy that reflects state law by August 2026.

Letters had been sent to families for about 10 years, she said.

“That really has not helped move the needle on chronic absence,” she said. “So instead of doing that, school districts have to come up with plans to more proactively intervene once they see students are missing for smaller amounts of time. They’ve got to help put together plans and supports for kids, instead of waiting until they just get to this number and then send a letter home.”

She said that a student struggling with reading may have an attendance problem.

“And it’s not necessarily because of anything outside of school, but if a student can’t read, maybe they’re embarrassed and they don’t want to come to school,” she said.

In that case, reading intervention would be part of their plan, she said.

Aldis said plans may be effective if the work doesn’t fall on teachers.

“You do worry about putting more and more work on teachers, if teachers end up doing it,” he said. “You don’t want to take them away from teaching and learning. I think the effectiveness of this will depend on where the responsibility falls. Teachers have enough on their plates; we don’t want them to corral missing students.”

Special ed, other students

About 270,000 Ohio students are on individualized education programs, which identify a student’s disability and create special education plan with support they need to learn. Thirty-four percent of Ohio’s special education students were chronically absent last school year, higher than the statewide average.

Just 19.1% of students with speech and language impairments were chronically absent last year, below the state average. However, students with other disabilities had a higher-than-average rate, all the way to 53.9% for students with emotional disturbance.

School psychologists evaluate students for individualized education programs, consult on data in and sometimes they even write IEPs. But psychologists are stretched. On average, there is one school psychologist for every 829 Ohio public school students, when the recommended level is one for every 500 students, said Jessica Kukura, a school psychologist involved in the Ohio School Psychologists Association.

“So when we look at our special education students aging up, our goal as a school psychologist is to identify student need to help remediate those needs and catch the student back up to grade-level success,” she said.

But if there are not enough professionals to help the students, by the time they reach high school they could be so behind they become discouraged and don’t want to attend school, Kukura said.

Disadvantaged students had higher rates of chronic absenteeism last year – including 58.9% of students experiencing homelessness, 33.6% of students in foster care and 33.3% of students from low-income families, state data shows.

Nearly half of students in Ohio’s major urban districts were chronically absent last year – 48.6%. This was higher than smaller urban, suburban, small town, rural and charter schools.

Eight districts part of the major urban category: Akron City, Canton City, Cincinnati City, Cleveland Metropolitan, Columbus City, Dayton City, Toledo City and Youngstown City. Together, they represent 12% of Ohio students, roughly 184,000 students.

Kukura said that there is higher poverty in major urban districts than in other types of districts. For instance, in suburban districts, the chronic absence rate last year was 16.4%.

“Our (urban) families are really struggling,” she said. “There’s a huge socioeconomic gap. There’s a huge resource gap.”

2025 School Report Cards

Which schools beat report card expectations, based on income? Ranking all 607 Ohio districts

School report cards 2025: Which Northeast Ohio districts improved?

How East Cleveland schools achieved 3-star rating after years of low tests, state takeover

Report cards: Ohio student math scores recovering from COVID-19, reading dips

Ranking all 607 Ohio public school districts by their 2025 report card test scores

Stay in the Game!

In 2015, the Cleveland Browns Foundation talked to then-CMSD CEO Eric Gordon about how it could support the schools. Gordon mentioned the district was about to launch an attendance campaign. The foundation started to work with the district on a program that eventually became known as the Stay in the Game! Attendance Network.

Stay in the Game today is an effort across the state, along with Pittsburgh public schools. In addition to the Browns, the Columbus Crew, FC Cincinnati and the Pittsburgh Steelers have joined the effort. Students receive materials from the teams to help track their attendance progress, messages from players and attendance certificates.

Districts choose to participate at different levels. A total of 219 districts are now involved, which educate about 575,000 students, said Renee Harvey, vice president of community impact and the Browns Foundation.

The districts can receive localized, data-informed attendance campaigns at schools or in classrooms. With the higher-level of participation, districts receive an interactive playbook to create a data-informed strategy for increasing attendance.

“I think oftentimes we look at the average, or the average daily attendance, which we’re really trying to steer districts away from, because that really masks the students who aren’t in school,” Harvey said. “We want them to be able to identify the students who aren’t coming to school, so they can lean in in a more direct manner, so they can build these strategies that really should canvas the entire year.”

Stay in the Game! works with the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, and Harvard’s Proving Ground, which tests solutions to improve attendance and works on data analysis and strategic advice, Columbus-based Battelle Foundation, which manages the network.

Stay in the Game! also breaks down chronic absence by severity. Trying to work on reducing days missed, even if a student remains chronically absent.

Stay in the Game! and DEW haven’t met to review whether attendance improved in 2024-2025 for students who participated in its programs.

In the past, Stay in the Game! works with school districts with higher-than-average chronic absence. Among those schools, chronic absence decreases by a higher percentage than the state average, said Horowitz-Moore of DEW.