“Do you smell that?” Florence Chesson was asked by a fellow Jet Blue flight attendant as they prepared for landing in Puerto Rico.

Chesson, as trained, inhaled a lungful of air through her nostrils in a single deep breath. “It smells like dirty feet,” she told her colleague.

Instantly, she started to feel like she had been drugged, Chesson said in an interview.

When the flight landed, the two cabin crew were taken to a hospital in an ambulance, one on a stretcher.

Chesson, her uniform and hair soaked in sweat and with an overpowering metallic taste in her mouth, went to meet her supervisors. “I felt like I was talking gibberish,” she recalled. “I remember being very repetitive, saying ‘What just happened to me? What just happened to me?’”

After months of worsening symptoms, Chesson was diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury and permanent damage to her peripheral nervous system caused by the fumes she inhaled. Her doctor, Robert Kaniecki, a neurologist and consultant to the Pittsburgh Steelers, said in an interview that the effects on her brain were akin to a chemical concussion and “extraordinarily similar” to those of a National Football League linebacker after a brutal hit. “It’s impossible not to draw that conclusion,” he said.

Kaniecki said he has treated about a dozen pilots and over 100 flight attendants for brain injuries after exposure to fumes on aircraft over the last 20 years. Another was a passenger, a frequent flier with Delta’s top-tier rewards status who was injured in 2023.

The Journal’s reporting—based on a review of more than one million FAA and National Aeronautics and Space Administration reports, thousands of pages of documents and research papers and more than 100 interviews—shows that aircraft manufacturers and their airline customers have played down health risks, successfully lobbied against safety measures, and made cost-saving changes that increased the risks to crew and passengers.

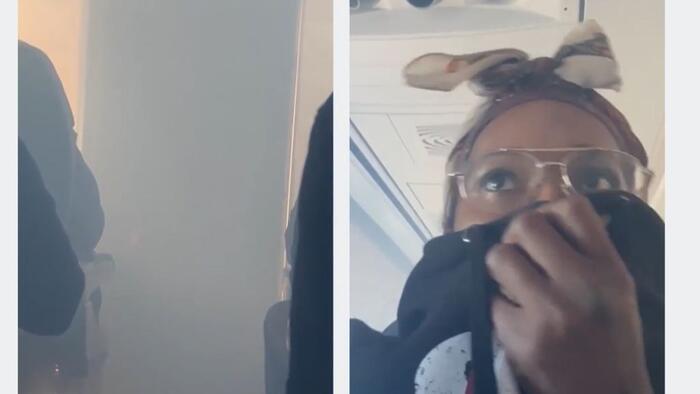

In a February incident captured on video by several passengers, enough oil entered the bleed air supply of a Boeing 717 that thick plumes of smoke started piling through the vents midflight. “Ladies and gentlemen, please breathe through your clothing, stay low,” the Delta Air Lines flight attendant told passengers, some of whom had noticed a strange smell during takeoff.

In a 2017 internal email, excerpts of which were produced in a lawsuit, Boeing quality inspector Steven Reiman wrote:

Just think what would happen if people realized they are being poisoned by coming to work on our airplanes or as passengers.

The FAA on its website says the incidents are “rare” and cites a 2015 review that estimated a rate of “less than 33 events per million aircraft departures.” That rate would suggest a total of about 330 fume events on U.S. airlines last year.

In reality, the FAA received more than double that number of reports of fume events in 2024 from the 15 biggest U.S. airlines alone, according to the Journal’s analysis of service difficulty reports for flights between 2010 and early 2025. The rate has soared in recent years. In 2014, the Journal found about 12 fume events per million departures. By 2024, the rate had jumped to nearly 108.

The Journal’s analysis suggests that the growth is driven by the world’s bestselling aircraft: the Airbus A320. In 2024, among the three largest U.S. airlines with mixed fleets, the rate of reports on A320s had increased to more than seven times the rate on their Boeing 737 aircraft.

At JetBlue and Spirit—both majority-Airbus operators—the increase is stark. Together, the airlines saw a 660% surge in the frequency of incidents on their A320s between 2016 and 2024.

The Journal’s analysis shows incidents began climbing in 2016, the year Airbus started delivering its new A320neo, what would become the world’s fastest-selling model. It boasted a new generation of fuel-efficient engines, including one that was plagued by rapidly degrading seals meant to keep oil from leaking into the air supply.

Under pressure from airlines who complained that fume events were keeping aircraft out of service for up to days at a time, Airbus loosened maintenance rules, according to a review of internal documents and people familiar with the changes.

The FAA inspector wrote:

These toxic chemicals are present in today’s modern synthetic jet engine oils and are passing into the aircraft cabin/cockpit unfiltered, affecting the air that crew and passengers breathe in.

‘Passed out pilots’

The United Nations has formally recognized fume events as a risk to flight safety since 2015. In addition, more than a dozen accident investigation teams in countries across the world have asked Boeing, Airbus and their regulators to implement measures to mitigate the risk, according to a review of official accident investigation reports. No major changes have been made.

One exception is the 787, Boeing’s first all-new design since smoking on commercial planes was fully banned in the U.S.

An email chain from Boeing’s early marketing meetings for the plane showed managers were grappling with how and whether to promote the new design. In one marketing brief it was referred to as “removing gaseous contaminants” from the air supply.

One executive was concerned that “if we elaborate on the 787 air purification and say how great and important it is,” he’d be asked why the system wasn’t available on Boeing’s other models, according to a deposition citing internal Boeing documents.

Congress is trying again. A bipartisan bill reintroduced last month would phase out the use of bleed air and require specialized filters on aircraft within seven years.

Due to a design element that has been a feature of almost every commercial jetliner since the 1950s, toxic fumes can leak from jet engines into the cabin or cockpit. The fumes have led to emergency landings, sickened passengers and crew members, and affected pilots’ vision and reaction times midflight, according to official reports.

The health effects are often mild but can also be severe, including brain injuries. Here’s what to know:

Where does the air on a flight come from?

On most planes, about half the air in the aircraft is recirculated. That refers to air that’s already on the plane that’s breathed in and exhaled by passengers with the remaining oxygen filtered and then pumped back inside the cabin. The other half is pulled from outside via the aircraft’s engines using a system known as “bleed air.” Engines are used for air supply on every modern aircraft, with the exception of Boeing’s 787.

Sorry, but why is my air pulled through an engine?

Good question! Because air at altitude is very thin and very cold, it has to be compressed and heated before it can be sent to us to breathe. Aircraft manufacturers realized in the 1950s that jet engines were already doing that work, and they decided to “bleed” the air from the engines’ compression chambers and then run it through air conditioners to get it back down to breathable temperatures. Fume events occur when engine oils and hydraulic fluids leak into that section of the engine.

How worried should I be?

It doesn’t happen often. The rates we identified in 2024 showed an incident rate on top U.S. airlines of 108 per one million departures, or roughly twice a day. But we also know that fume events are massively underreported. Internal industry data reviewed by the Journal estimated a rate of 800 incidents per million flights in the U.S., or just about 22 a day. Still, as one researcher put it, it’s highly unlikely you’ll be exposed, but almost guaranteed it’ll happen on an aircraft somewhere in the U.S. today.

What about dropdown oxygen masks and existing air filters? Should I bring my own mask?

Because dropdown passenger oxygen masks aren’t sealed, they don’t provide proper protection. In one extreme fume event investigated by the FAA, passengers stood on their seats to break into the overhead compartments to access the masks—that’s a safety hazard that can cause other problems on a flight.

Cloth and even N95 masks also aren’t designed to filter vapors and gases. Until fume events have been addressed, often the best bet is to flag it to your cabin crew.

Why do cabin crew appear to be the most at risk?

There’s some evidence indicating that repeat exposures coalesce to cause more-severe damage. Cabin crew aren’t just flying more, but are also more active when they do. That means their breathing rates are typically higher than a seated and docile passenger.

While pilots have longer-lasting emergency oxygen supplies, cabin crew only have access to 15-minute oxygen tanks, which is often shorter than it takes for a pilot to divert and land the aircraft. Prolonged use of that oxygen supply is also dangerous.

Also, it’s possible we’re only more aware of affected crew because of the lack of awareness among passengers. Whereas crews have avenues to report their exposure, passengers don’t. Because symptoms can take time to fully manifest, the connection between exposure and symptoms becomes harder to make.