By Dan Adler

Copyright vanityfair

Before what would become a full day of testimony and arguments got underway, the crowd on hand on Friday morning was among the largest and most fervid since opening statements in the case began in May. For all the fanfare, the proceedings against Combs had generally amounted to something of a letdown for the class of chroniclers who became most invested in them. With his decades of fame and extensive celebrity connections, embodied in his Hamptons White Parties, the sex trafficking and racketeering charges against Combs seemed to many to promise a glimpse into the misdeeds of the rich and high-profile. But the trial primarily centered on the accounts of two women: Casandra “Cassie” Ventura, his ex-girlfriend, who first sued Combs before they quickly settled, and an anonymous witness. Both women recounted a grim trail of abuse and addiction between Combs, themselves, and the male escorts whom he paid for the elaborate, days-long sexual performances that he orchestrated, now known somewhat casually in the public consciousness as “freak-offs.”

“I actually thought this case was going to be more than what it was,” Armon Wiggins, a Los Angeles-based YouTube personality, told me this week. Wiggins made his way to New York for the trial thanks to donations from his viewers; he had previously covered the 2022 trial of Tory Lanez, when the rapper was convicted of shooting Megan Thee Stallion, and resolved to see Combs’s case unfold as soon as Ventura sued.

“We hadn’t had such a big trial for hip hop culture since OJ,” Wiggins said.

Throughout Combs’s trial, independent media creators filled the sidewalks outside Daniel Patrick Moynihan Courthouse with iPhone tripods to air their competing livestreams. Wiggins was at the fore, especially after the verdict arrived: when he poured baby oil on himself amid the celebrations, a reference to the product frequently invoked by prosecutors for having been stocked by Combs, the stunt made its way into more traditional media channels. (He quickly apologized on Instagram.)

The case revolved around often wrenching testimony from Ventura and Jane Doe, but Wiggins was well-positioned to summarize how his cohort tended to view their accounts.

“This was really about his freaky sex life,” he said. “As time went on, you saw people that were against him started saying, We don’t give a shit.”

“Clearly the jury thought the same thing,” he added.

In the end, after a hearing that stretched out over the course of seven hours, Judge Arun Subramanian, a Joe Biden appointee and former clerk for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, sentenced Combs to just over four years in prison. Ahead of the sentencing, prosecutors and defense lawyers had been making their case in court filings that offered a window into how Combs’s tailspin had been processed across the far-flung quarters of his life.

Yung Miami, the rapper born Caresha Brownlee and a recent girlfriend of Combs’s, wrote in a character letter on his behalf that one of her “most meaningful memories was when he took me to my first Met Gala.”

“Sean has always made it a priority to open doors for Black people,” she added, “to make sure we are seen, heard, and valued in spaces where we’ve historically been excluded.”

Deonte Nash, a former stylist for Combs writing in the government’s sentencing submission, said, “Many of us were abused precisely because Mr. Combs wanted us to hold his secrets to maintain his “reputation.””

“Judge..That’s a good man,” Brownlee wrote.

“Judge, this is not a good man,” Nash said.

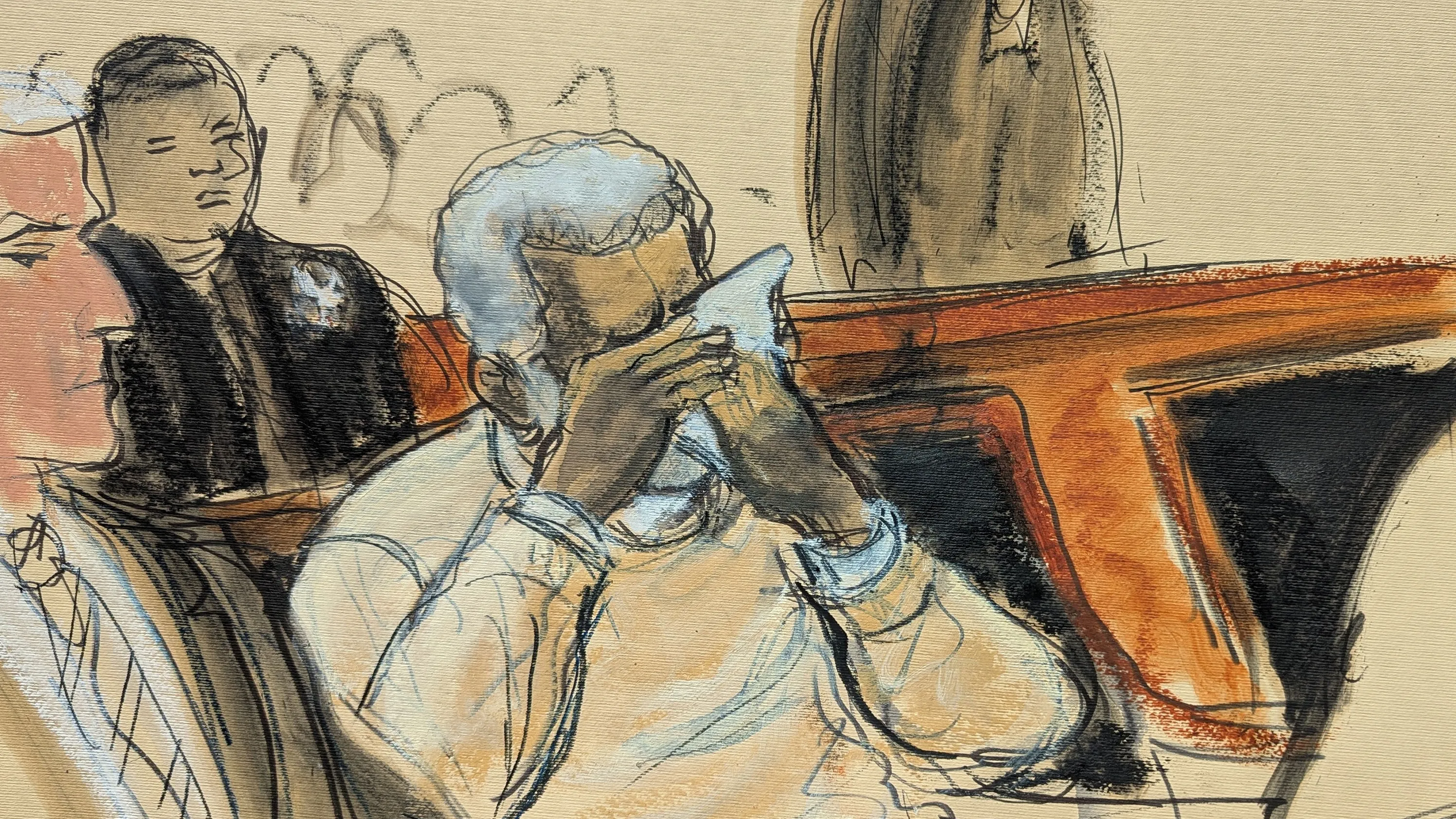

After his lawyers and prosecutors spoke, Combs addressed the judge—his lengthiest public comments on the legal saga that has enveloped him since Ventura first sued. (He declined to testify at trial.)

“I want to thank you for giving me the chance to finally speak up for myself,” Combs said.

He framed his remarks in part as an apology to Ventura and Jane Doe. “I brought you into my mess,” Combs said, describing his behavior as ‘disgusting, shameful, and sick.”

“I’m not this larger-than-life person,” Combs said he had come to realize. “I’m just a human being.”

His statement clocked in a little over ten minutes, and he acknowledged the extensive furor surrounding him. “No matter what anybody says,” Combs said, “I know that I’m truly sorry for it all.”

In fighting the charges he faced, Combs has also launched an offensive around the gossip ecosystem that has sprung up around him. This week, his publicist sent out email blasts with each update in his sentencing submission, and his attorneys have taken to filing defamation suits against some of the parties registering the most sensational theories of his wrongdoing.

Ventura was not in the courtroom on Friday, but her contribution to the prosecution’s sentencing submission gave some sense of how she navigated the spectacle surrounding case. “I have been in a cycle of thought and then over thought writing this letter to you,” she wrote to the judge. “If there is one thing I have learned from this experience, it is that victims and survivors will never be safe. Although I can hope for justice and accountability, I have come to not trust anything. I hope that your decision considers the truths at hand that the jury failed to see.”

Privacy and quiet had become her priorities, Ventura wrote, and she had moved her family out of the New York area, fearing retribution from Combs and his associates. “He will always be the same cruel, power-hungry, manipulative man that he is,” she said. “When I came out with my allegations in my civil case, he flatly denied them again and again. It was only after actual video footage corroborated the exact words in my civil complaint that he issued an insincere apology on the internet.”