A new listing of the 50 most concerning pieces of space debris in low-Earth orbit is dominated by relics more than a quarter-century old, primarily dead rockets left to hurtle through space at the end of their missions.

“The things left before 2000 are still the majority of the problem,” said Darren McKnight, lead author of a paper presented Friday at the International Astronautical Congress in Sydney. “Seventy-six percent of the objects in the top 50 were deposited last century, and 88 percent of the objects are rocket bodies. That’s important to note, especially with some disturbing trends right now.”

The 50 objects identified by McKnight and his coauthors are the ones most likely to drive the creation of more space junk in low-Earth orbit (LEO) through collisions with other debris fragments. The objects are whizzing around the Earth at nearly 5 miles per second, flying in a heavily trafficked part of LEO between 700 and 1,000 kilometers (435 to 621 miles) above the Earth.

An impact with even a modestly sized object at orbital velocity would create countless pieces of debris, potentially triggering a cascading series of additional collisions clogging LEO with more and more space junk, a scenario called the Kessler Syndrome.

McKnight, a senior technical fellow at the orbital intelligence company LeoLabs, spoke with Ars before the paper’s release. In the paper, analysts considered how close objects are to other space traffic, their altitude, and their mass. Larger debris at higher altitudes pose a higher long-term risk because they could create more debris that would remain in orbit for centuries or longer.

Russia and the Soviet Union lead the pack with 34 objects listed in McKnight’s Top 50, followed by China with 10, the United States with three, Europe with two, and Japan with one. Russia’s SL-16 and SL-8 rockets are the worst offenders, combining to take 30 of the Top 50 slots. Here’s the Top 10:

A Russian SL-16 rocket launched in 2004

Europe’s Envisat satellite launched in 2002

A Japanese H-II rocket launched in 1996

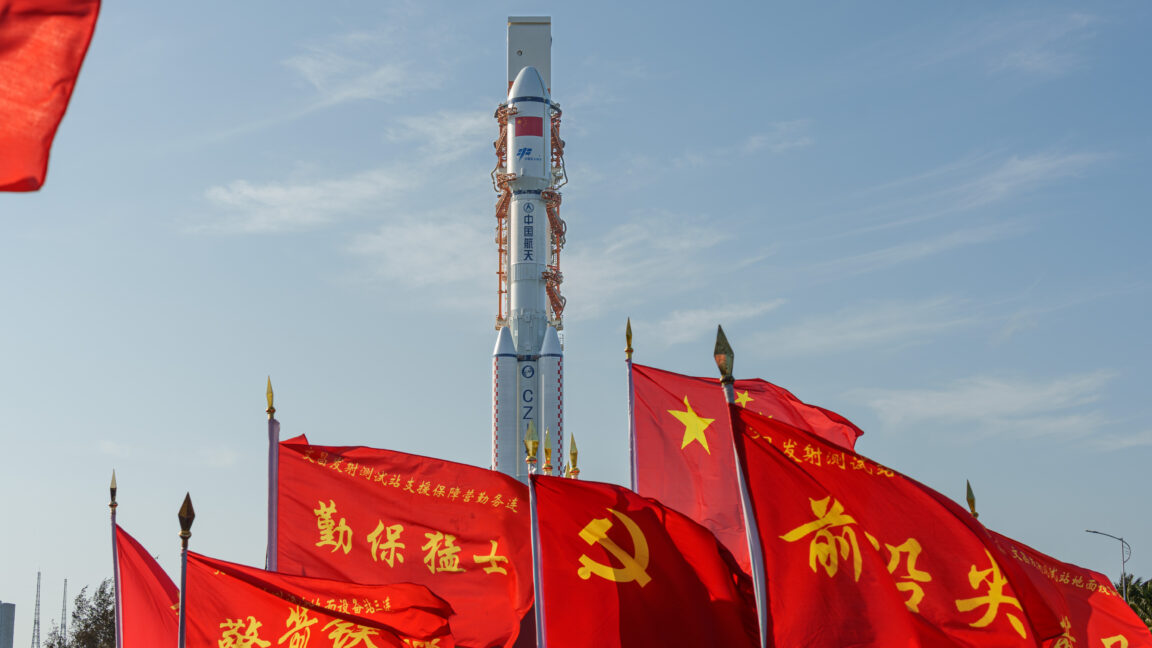

A Chinese CZ-2C rocket launched in 2013

A Soviet SL-8 rocket launched in 1985

A Soviet SL-16 rocket launched in 1988

Russia’s Kosmos 2237 satellite launched in 1993

Russia’s Kosmos 2334 satellite launched in 1996

A Soviet SL-16 rocket launched in 1988

A Chinese CZ-2D rocket launched in 2019

The list published Friday is an update to a paper authored by McKnight in 2020. This year’s list goes a step further by analyzing the overall effect on debris risk if some or all of the worst offenders were removed. If someone sent missions to retrieve all 50 of the objects, the overall debris-generating potential in low-Earth orbit would be reduced by 50 percent, according to McKnight. If just the Top 10 were removed, the risk would be cut by 30 percent.

A troubling trend

“The bad news is, since January 1, 2024, we’ve had 26 rocket bodies abandoned in low-Earth orbit that will stay in orbit for more than 25 years,” McKnight told Ars.

The 25-year discriminator is important because that is the guideline promulgated by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, an international group that includes representatives from all of the major space powers: the United States, China, Russia, Europe, India, and Japan. If a piece of space junk is left in low enough of an orbit, aerodynamic resistance will drag it back into the atmosphere in less than 25 years.

US and European governments have policies requiring launch companies to deposit their spent upper stages to altitudes low enough to naturally reenter the atmosphere within 25 years, or deorbit their rockets altogether. For example, SpaceX routinely deorbits the upper stages of its Falcon 9 rocket, usually driving them back into the atmosphere over an unpopulated part of the ocean. The policy does not apply to missions delivering satellites to altitudes above low-Earth orbit.

China, on the other hand, frequently abandons upper stages in orbit. China launched 21 of the 26 hazardous new rocket bodies over the last 21 months, each averaging more than 4 metric tons (8,800 pounds). Two more came from US launchers, one from Russia, one from India, and one from Iran.

This trend is likely to continue as China steps up deployment of two megaconstellations—Guowang and Thousand Sails—with thousands of communications satellites in low-Earth orbit. Launches of these constellations began last year. The Guowang and Thousand Sails satellites are relatively small and likely capable of maneuvering out of the way of space debris, although China has not disclosed their exact capabilities.

However, most of the rockets used for Guowang and Thousand Sails launches have left their upper stages in orbit. McKnight said nine upper stages China has abandoned after launching Guowang and Thousand Sails satellites will stay in orbit for more than 25 years, violating the international guidelines.

It will take hundreds of rockets to fully populate China’s two major megaconstellations. The prospect of so much new space debris is worrisome, McKnight said.

“In the next few years, if they continue the same trend, they’re going to leave well over 100 rocket bodies over the 25-year rule if they continue to deploy these constellations,” he said. “So, the trend is not good.”

There are technical and practical reasons not to deorbit an upper stage at the end of its mission. Some older models of Chinese rockets simply don’t have the capability to reignite their engines in space, leaving them adrift after deploying their payloads. Even if a rocket flies with a restartable upper stage engine, a launch provider must reserve enough fuel for a deorbit burn. This eats into the rocket’s payload capacity, meaning it must carry fewer satellites.

“We know the Chinese have the capability to not leave rocket bodies,” McKnight said. One example is the Long March 5 rocket, which launched three times with batches of Guowang satellites. On those missions, the Long March 5 flew with an upper stage called the YZ-2, a high-endurance maneuvering vehicle that deorbits itself at the end of its mission. The story isn’t so good for launches using other types of rockets.

“With the other ones, they always leave a rocket body,” McKnight said. “So, they have the capability to do sustainable practices, but on average, they do not.”

Since 2000, China has accumulated more dead rocket mass in long-lived orbits than the rest of the world combined, according to McKnight. “But now we’re at a point where it’s actually kind of accelerating in the last two years as these constellations are getting deployed.”

China is prioritizing the Guowang and Thousand Sails constellations. These networks are likely akin to SpaceX’s Starlink broadband constellation, although there is some evidence that the Guowang program, in particular, has a military purpose.

“In their rush to move quickly, they are adding to the long-term collision hazard,” McKnight said.

The deputy head of China’s national space agency, Bian Zhigang, addressed the International Astronautical Congress on Monday. He was asked about China’s commitment to good stewardship of the space environment. Bian acknowledged a “very serious challenge” in this area, “especially with megaconstellations.” He did not mention China’s problem with leaving rockets in orbit.

Bian said China is “currently researching” how to remove space debris from orbit. One of the missions China claims is testing space debris mitigation techniques has docked with multiple spacecraft in orbit, but US officials see it as a military threat. The same basic technologies needed for space debris cleanup—rendezvous and docking systems, robotic arms, and onboard automation—could be used to latch on to an adversary’s satellite.

Silver lining

McKnight and his coauthors (from the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, and Russia) went the extra mile to assess how the space debris threat would change if some of the most hazardous objects dropped off the list. He said the results are promising.

“If you take out 10 of the objects, you reduce it by 30 percent,” McKnight said. “That’s a measurable change. I think that’s what’s been missing in the past about justifying active debris removal.”

Active debris removal is an elusive proposition. While it is technically feasible, as several missions have shown, there’s the question of who pays. Is there a viable market for space debris cleanup services? The European Space Agency and Japan’s space agency have invested low levels of funding in debris removal initiatives. One of these projects, led by a Japanese company named Astroscale, completed a successful demonstration last year to set the stage for a future attempt to dock with a defunct Japanese rocket and steer it back into the atmosphere.

Astroscale was founded in 2013 for the purpose of ridding low-Earth orbit of space junk. Realizing the limited market for those missions, the company has pivoted to also pursue satellite servicing and refueling technology.

“We can make a measurable impact on the debris-generating potential, and the potential for the onset of the Kessler Syndrome by removing 10 or 20 objects,” McKnight said. “The bad news is we just added 26 new objects in the last two years.”