Leaders of SERVIR gathered at NASA headquarters in February to mark the 20th anniversary of the NASA–U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) program, which helps developing nations tackle environmental challenges using Earth observation data.

“We had a birthday cake and a big celebration,” said David Saah, director of the University of California Geospatial Analysis Lab and head of the Spatial Informatics Group, a SERVIR partner.

“That’s when we got the termination notice.”

NASA, one of SERVIR’s founding partners, informed public and private organizations that it was ending all SERVIR agreements and contracts. The news came shortly after USAID, which provided the bulk of SERVIR funding, pulled out of the program.

Without U.S. government support, SERVIR was widely expected to crumble.

But now, nearly eight months later, the work continues.

Regional institutions, universities, foundations and government agencies from around the world came together to establish the SERVIR Global Collaborative.

“What NASA built with SERVIR is alive and thriving,” said Saah, the SERVIR Global Collaborative’s senior scientist. “The program has been tested and has shown that it can run on its own, leveraging collaborative partnerships and open science in a community eager to make the world a better place.”

New funding

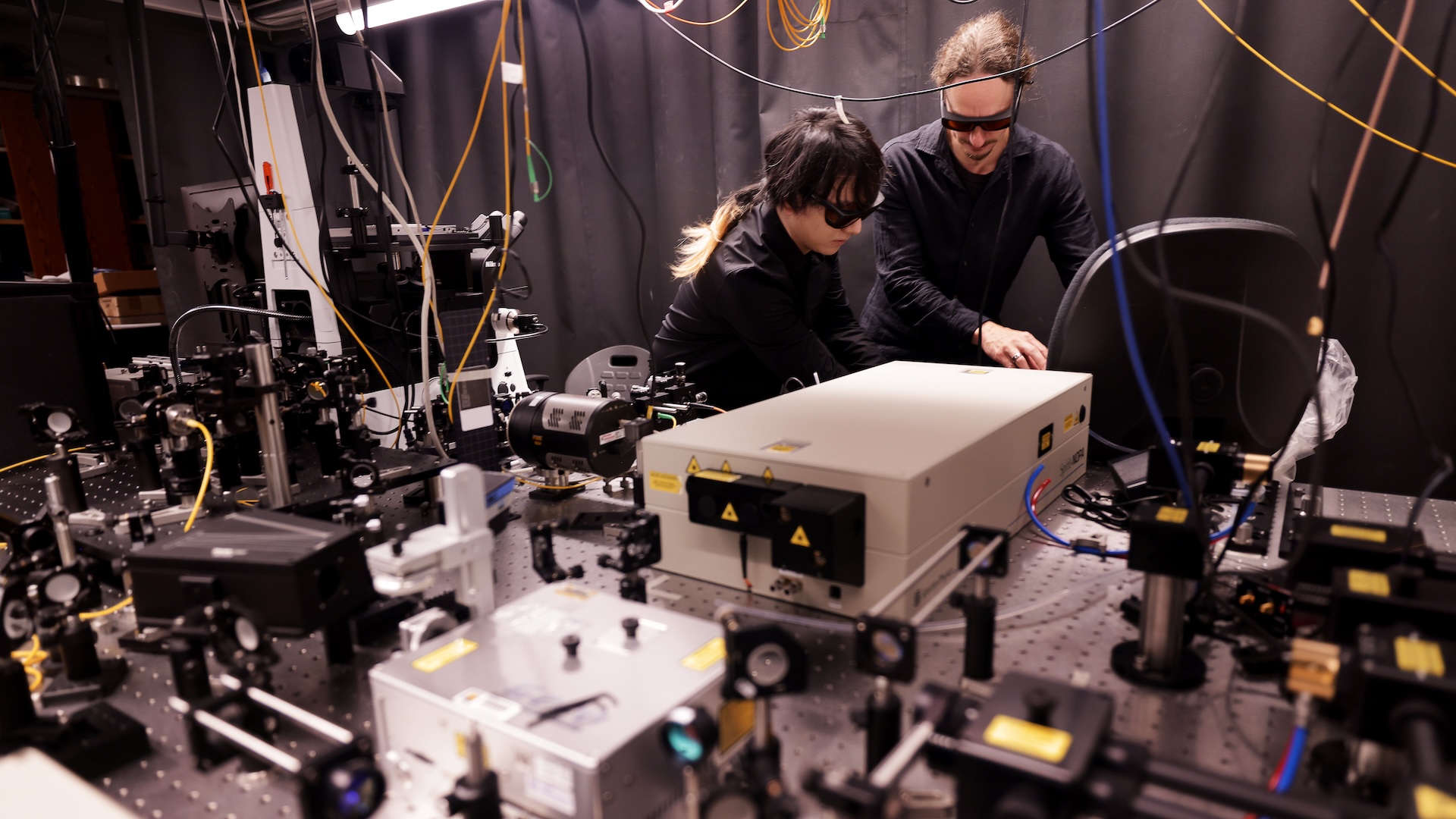

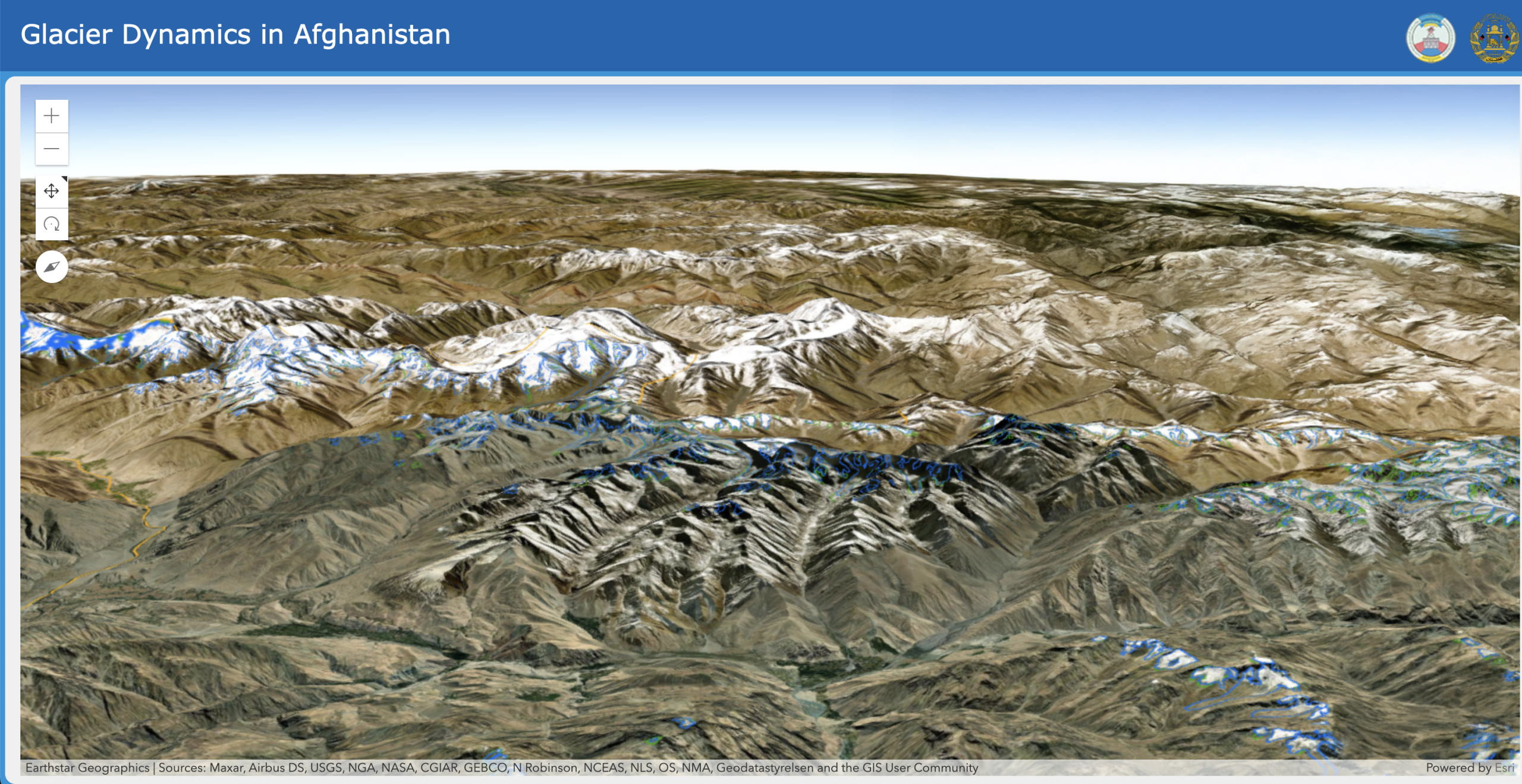

The SERVIR program relied on Earth-observation satellites and data gathered in space to help communities on the ground manage environmental challenges. By using information from NASA and other partner satellites, it could monitor weather, vegetation, water resources and land use — data that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to collect solely from Earth’s surface. Equipped with this information, the program could track deforestation and erosion, monitor air quality, predict floods or droughts and measure the impacts of climate change.

Like its government-backed predecessor, the SERVIR Global Collaborative combines satellite imagery and data with local observations and geospatial expertise to help communities grappling with similar problems.

Work is continuing in 50 countries in Africa, Asia and Central and South America. The Collaborative provides guidance and resources to foster local initiatives.

Financial support — much of which is undisclosed — is coming from public and private organizations. Regional hubs working with local institutions are establishing “diverse sources of funding to become more resilient,” Saah said.

And while the Collaborative maintains SERVIR’s geographic hubs, the global footprint of projects is changing. In the past, USAID approved regions and countries for SERVIR activities. Since the U.S. government no longer provides funding, U.S. agencies can no longer bar the organization from working in specific areas due to national security, technology transfer or data-sharing concerns.

“Now, we’re not constricted by the U.S. government. Now, we can work wherever the need is,” Saah said.

Sharing expertise

SERVIR was established to combine NASA satellite-based Earth-observations and geospatial tools with USAID’s expertise in helping individuals and institutions solve problems in a sustainable manner.

Since then, the two U.S. agencies have spent tens of millions of dollars building regional hubs and providing communities around the world with computers, software and expertise to make sense of satellite imagery.

In December, for example, NASA and USAID announced a $6.6 million investment in a new Central American SERVIR hub in Costa Rica at the headquarters of the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE).

While USAID was SERVIR’s primary funder, NASA paid scientists to propose environmental projects and to expand each hub’s ability to address local concerns with Earth-observation data. NASA’s SERVIR Applied Sciences Teams trained nearly 10,000 professionals to use remote-sensing data in local decision-making during the first 16 years of the program, according to a 2021 NASA study.

Cash crunch

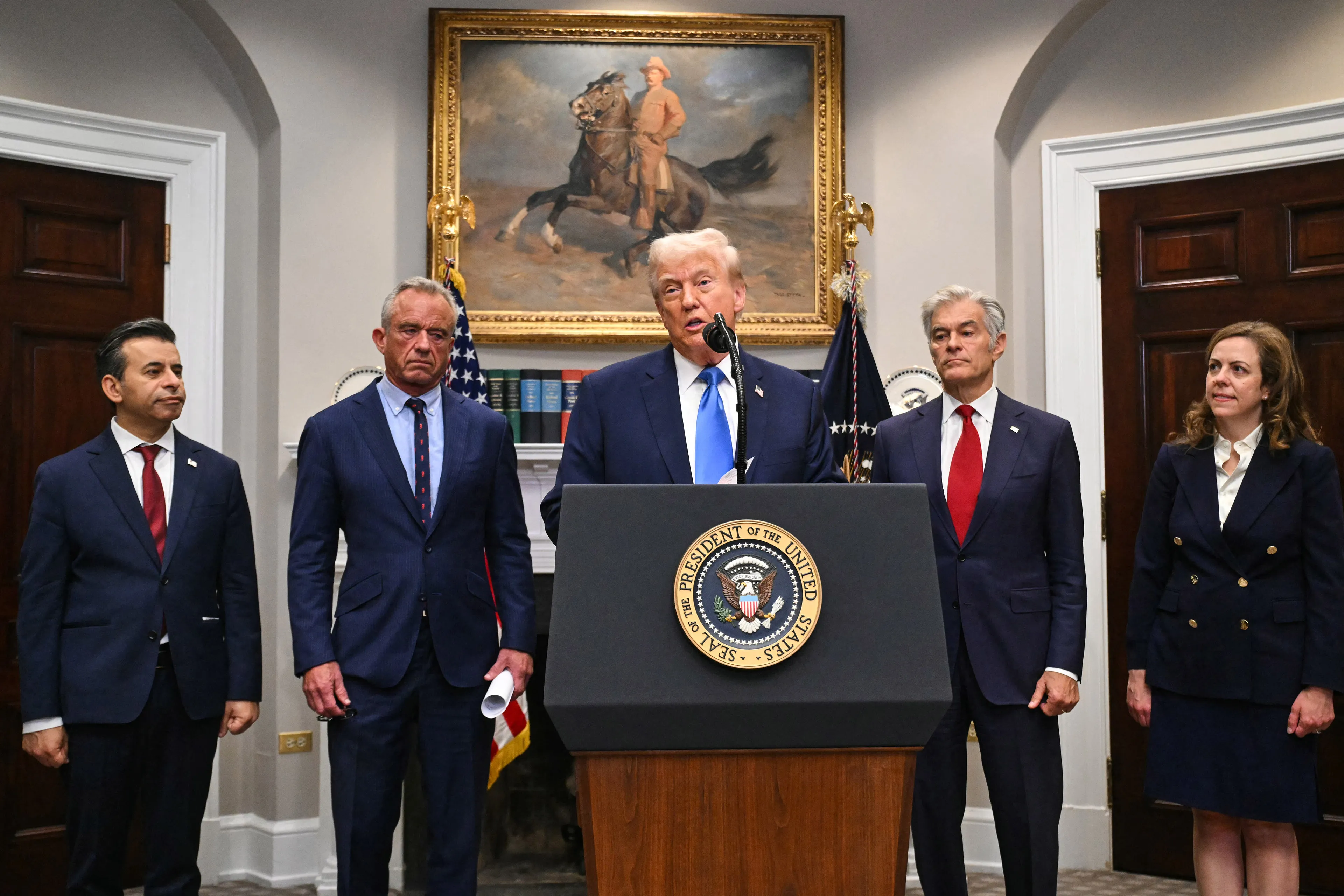

Funding for SERVIR, like money for the vast majority of U.S. foreign-assistance programs, was halted by an executive order President Trump signed on Jan. 20, the first day of his second presidency. USAID told SERVIR partners and NASA in mid-February that all contracts and agreements would end on March 30. The next day, NASA announced that it could not continue SERVIR without USAID.

At that point, SERVIR leaders heard from partners around the world who said that they wanted to continue SERVIR’s work. That included groups such as Ecuador’s EcoCiencia Foundation, a nonprofit committed to preserving biodiversity; Imaflora, a Brazilian nongovernmental organization focused on conservation and sustainable use of natural resource; and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, a Columbian agricultural research center committed to reducing poverty and protecting natural resources.

“There was a demand by the folks in the network to continue, an expectation that we would stand on our own,” Saah said. “We’ve hit hard times before. What makes us strong is that we can move forward through these hard times together.”

Flexible approach

Before cutting ties with SERVIR, NASA transferred digital assets including domain names and LinkedIn feeds to the Collaborative. International partners then worked together to update the branding and bring websites back online.

At the same time, the leaders of the Collaborative’s global hubs began meeting weekly to discuss priorities for the new organization. Decisions were made by consensus.

Plans for the new regional hub in Costa Rica were canceled because they were tied to USAID objectives. “The current approach is more flexible and better aligned with on-the-ground realities,” Alejandro Solis, director of outreach and strategic partnerships for CATIE, a Collaborative founding member, said by email.

“CATIE continues to run a variety of projects, many of which are in agriculture and environmental areas that require geospatial and remote-sensing approaches,” Solis said. “While the SERVIR program as we knew it has ended, the other projects are still active and moving forward.”

A moment to innovate

Once the websites were restored and news of the Collaborative spread, “foundations started jumping in to fund different components,” Saah said.

To date, contributions have been made under nondisclosure agreements that prevent the Collaborative from sharing funder names, dollar values or program details. In addition, national and regional development organizations are backing the Collaborative.

“They know that we have a portfolio of science that has been proven effective,” Saah said. “We have a network of institutions and individuals that have been proven to be robust and sustainable.”

Now, Saah and his colleagues are attending conferences and events “to tell the universe that we’re still alive and still fulfilling those commitments we made to all these local and government organizations,” Saah said.

“For us as a hub, this is an exciting moment to innovate, to rethink how we respond to stakeholders’ needs, ensuring they are at the center of our efforts, while also reducing overreliance on philanthropic support,” Solis said.

This article first appeared in the October 2025 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.