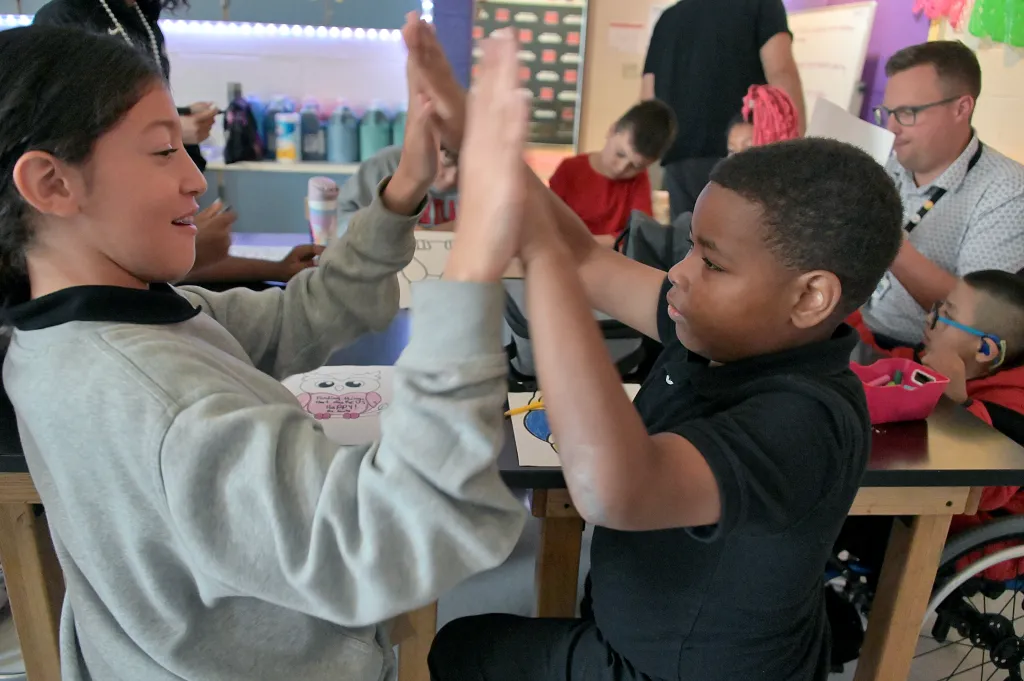

Fifth-graders Emily Ortiz and Colby Street sit side-by-side in their elementary school class, coloring pictures of an owl.

They’re part of a 10-member “Inclusion Squad” at Armistead Gardens Elementary/Middle School that meets every Wednesday for group activities, combining students with disabilities with their general education peers. The school is the first in the Baltimore City public school system to receive national recognition as a Special Olympics Unified Champion School for its inclusion efforts.

“To be the only Baltimore City public school to have this achievement speaks volumes when you consider the resources andwhat-not in other districts,” said school psychologist Jennifer Kelly, who helps run the club. “It speaks to our kids and our staff and our programming.”

The club started organically, when some of the general population students started playing and interacting during recess with others who are part of the citywide class for those with cognitive and adaptive disabilities, Kelly said. Almost all students in the citywide program participate in Special Olympics once they reach age 8, and some other students at the school support them at their events.

Colby is a Special Olympics athlete, participating in bowling and the spring games. Emily said she and Colby met in music class two years ago, where Colby would run around and talk about how much he likes lions. “We’re good friends,” she said.

Armistead Gardens is one of 19 schools in Maryland to receive Special Olympics national banner recognition for their inclusion efforts, Kelly said. The school has around 800 students, and 40 who participate in citywide classrooms, Holbrook said. It’s one of 20-25 public schools in Baltimore with a citywide program, he said.

The challenge with special programs is making sure they don’t become an “island” within the school, and that the students and parents all feel included, Holbrook said.

“A Special Olympics inclusion project gives us a chance to kind of bridge the gap,” he said.

A majority of the school’s population at Armistead live in the neighborhood, and many walk to school, which could make those who come by bus for citywide programs feel isolated, Kelly said. She said the staff works hard to make sure everyone feels included.

The club has helped students who struggle with language and social interactions to have those skills modeled for them by other students, Kelly said. Some students will help serve as translators for other kids with Down Syndrome or other disabilities, she said. Last year, one of the Inclusion Squad members decided to spend his birthday by having a pizza party in the citywide classroom with some of his friends there.

“It’s really just been great to see all of the kids flourish, particularly our friends who have disabilities,” Kelly said. “The other kids may not really know what makes them different or the same, or that they are different or the same. They just know that there are Inclusive Squad friends or buddies.”

On World Down Syndrome Day in March, the school did a school-wide awareness campaign for Down Syndrome, with kids wearing mismatched socks reflecting mismatched chromosomes.

“We don’t talk about, like, if anyone has a disability … but we just talk about things that make us the same and things that make us different,” Kelly said.

The kids considered names for their group like the “Inclusion Club” or “Kindness Cooperative.” They settled on the “Inclusion Squad” since that sounded “much cooler,” Kelly said.

Kelly said other schools have asked about the work Armistead Gardens is doing with the Inclusion Squad.

“It’s really kind of taken off and become this thing that we never thought it would become.”

Have a news tip? Contact Brooke Conrad at bconrad@baltsun.com or 443-682-2356.