EL GUAYABO, Michoacán, Mexico — The armored vehicle, or what now remained of it, lay abandoned in the road where a landmine had blown it up. The bodies of the vehicle’s occupants, cartel sicarios who had been killed as they tried to flee, were nowhere to be found when we examined the incinerated wreckage several days later. Neither, though, were most residents of the surrounding village, who had fled en masse to escape the same fate.

Nearly the entire population of El Guayabo, approximately 400 to 500 dirt-poor lime pickers living on communal land in the west Mexican state of Michoacán, fled hastily in mid-July to escape combat between the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, known as CJNG, and the Caballeros Templarios. When I went before dawn on July 30 with local human rights defenders to help displaced residents recover some of their belongings, the windows in every house were shattered by gunfire, roofs were blown open by bombs dropped from internet-bought drones, and everyone walked nervously, scanning the ground for landmines. Scattered everywhere were thousands of dull bronze shell-casings: .50 caliber rounds for sniper rifles and machine guns, 5.56 rounds for AR-15s and similar rifles, and 7.62×39 shells used for AK-47-style rifles.

Putting a stop “to every terrorist thug smuggling poisonous drugs into the United States,” as President Donald Trump put it to the United Nations last week, has become his self-proclaimed mission. His administration designated CJNG and Carteles Unidos — an umbrella of armed groups that includes the Templarios — as foreign terrorist organizations in January, allowing the U.S. government to crack down on any individual or group who provides them with “material support” or “expert advice and assistance.” During the first weeks of Trump’s administration, as a Washington Post investigation recently revealed, DEA agents pushed for “targeted killings of cartel leadership and attacks on infrastructure” in Mexico but faced pushback from some administration insiders. And in late July, Trump secretly signed a directive authorizing the Pentagon to use unilateral military force against Latin American drug cartels.

Since then, Trump says the U.S. has launched airstrikes against at least three alleged drug boats in international waters near Venezuela, killing 17 people. On Thursday, The Intercept obtained a leaked document circulated to congressional committees in which Trump declares the U.S. engaged in “non-international armed conflict” with the cartels. While the administration’s public ire has focused on Venezuela, sources within the Pentagon’s Northern Command have said they would have plans for potential strikes against Mexican cartels, too, “ready by mid-September.”

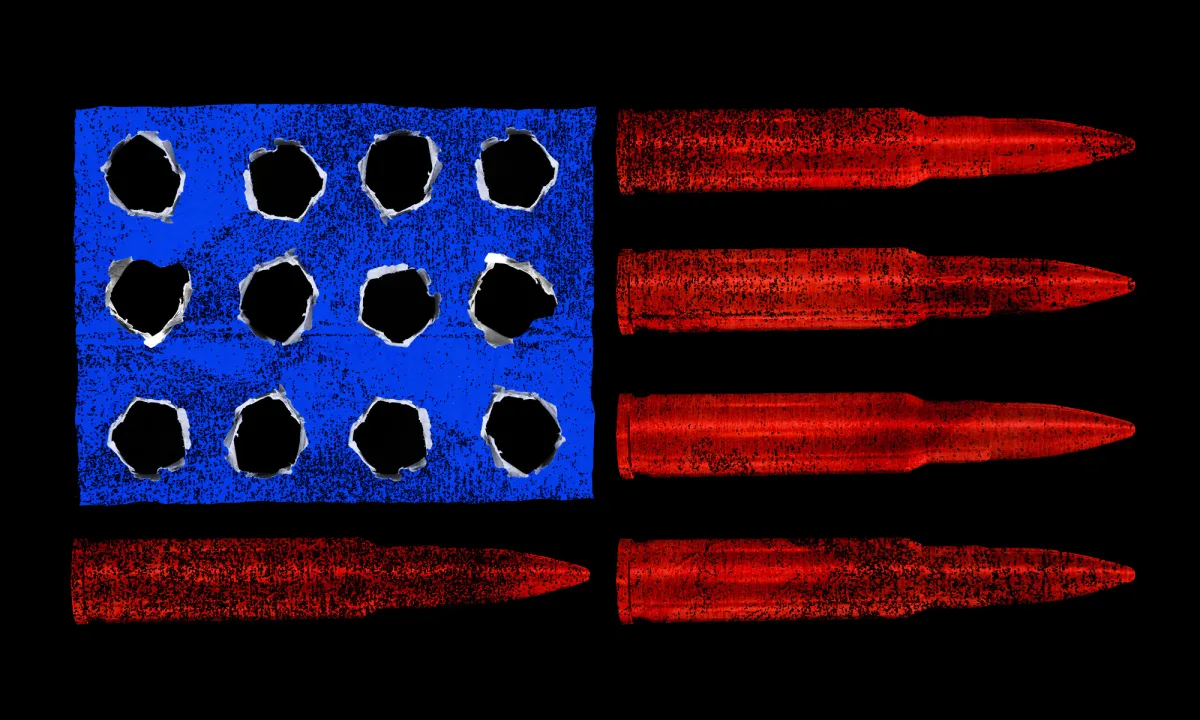

If the U.S. military does confront the cartels in Mexico, it will find itself facing battle with its own weapons. An investigation by The Intercept traced the bullets that littered the ground in El Guayabo to at least two U.S. firearms manufacturers, one of which operates a massive factory owned by the U.S. military. The Intercept gathered 123 shell casings, some of whose numbered headstamps corresponded to the now-defunct St. Louis Ammunition Plant and Lake City Ammunition — a commercial ammunition factory in Independence, Missouri, operated by Winchester and owned by the U.S. Army.

This investigation is the first of its kind to document the cartels’ use of ammunition from the U.S. Army-owned factory in enforcing mass displacement in Mexico. While past work has focused on the factory’s ties to mass shootings in the U.S. and the deaths of U.S. citizens, The Intercept’s investigation analyzes U.S.-made shells collected directly from the scene where some of Mexico’s poorest residents fled for their lives to escape ferocious gun battles between paramilitary groups — the same ones the Trump administration now classifies as terrorists.

“The United States is perfectly capable of breaking down criminal groups involved in the drug trade,” said Julio Franco, a human rights advocate at the Apatzingán Observatory for Citizen Security, “simply by closing off the pipeline of weaponry produced in the U.S. and used by Mexican criminal groups.”

Yet the Trump administration is doing the opposite. Trump plans to slash over two-thirds of the weapons investigators at the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives charged with ensuring guns sold by U.S. suppliers don’t end up in the hands of Latin American cartels and gangs, incinerating the already understaffed bureaucratic safeguards designed to stop the cartel weaponry pipeline.

The ATF, the U.S. Army, and the White House did not respond to The Intercept’s requests for comment. A representative for the Pentagon said they didn’t have responses to The Intercept’s questions, citing the government shutdown.

Experts estimate that around 200,000 military-grade assault weapons and machine guns are trafficked every year from U.S. gunshops to Mexican criminal groups, moving south across the border with little to no scrutiny. This unchecked flow of weapons, longtime weapons experts told The Intercept, represents a massive missed opportunity in the country’s stated mission to kneecap the cartels.

In villages like El Guayabo, this neglect fuels warfare while driving mass displacement. The Ibero-American University and the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights registered 28,900 newly displaced people in at least 72 mass displacement events in Mexico last year, according to a report released in June. At least 392,000 people have been displaced since the U.S.-backed drug war was revamped in 2006, though experts estimate that to be a significant undercount. Franco estimated that several thousand have been displaced in El Guayabo since 2021, though the lack of recognition or authoritative studies means that figure too is likely an undercount.

Franco was in El Guayabo on July 30 with The Intercept and Carmen Zepeda, a teacher, humanitarian activist, and Apatzingán councilwoman for Morena, the dominant political party in Mexico. As one of the leading advocates for the victims of enforced displacement in Michoacán, Zepeda pointed to a growing list of villages where thousands have fled armed conflict: Acatlán, Loma de los Hoyos, el Mirador, el Manzo, Las Bateas, Llano Grande, El Tepetate, La Alberca, San José de Chila, El Alcalde, and El Guayabo — all in the municipality of Apatzingán.

“There’s a war in this municipality,” said Zepeda. “And this war is being carried out with bullets from the United States.”

The man taking the video growls at the bodies, two skinny young men, one with his mouth frozen open, sprawled out dead in the mud. “Just so you sons-of-bitches see, so you don’t keep coming to El Guayabo you motherfuckers, we warned you, you thought it was a game,” the man shouts in Spanish, out of breath, as he assesses the carnage under a soft, steady rain. Flanking the bodies are the steaming carcasses of two blown-up monstruos, the homemade armored vehicles used by cartels. “So you motherfuckers see how you’ll fucking end up, your mouth full of flies. Fucking Templas all the way.” A photo of the same monster under the same rainy sky shows five men in civilian and military clothing with bulletproof vests and assault weapons. Scattered on the ground alongside the bodies lay the dull bronze spent ammunition.

This was the aftermath of a brutal gunfight in El Guayabo on July 24, filmed by a sicario and uploaded to Telegram, six days before The Intercept made the trip to the village. When we walked along a dirt road at dawn, the bodies of the dead men, identified as 27-year-old Gustavo Javier Salazar and 24-year-old Victor Manuel de Jesús Pérez Ortíz, were gone. An official at the General State Prosecutor’s office in Apatzingán, who identified the men and requested anonymity to disclose the information, later said prosecutors seized 7.62×39 and .50 caliber ammunition, though they didn’t find the 5.56 rounds The Intercept later discovered.

The ammunition, according to residents as well as videos uploaded to social media and Telegram channels, was used by gunmen pertaining to the Caballeros Templarios, an armed wing of the Carteles Unidos, one of Trump’s designated FTOs. Fighting alongside the CJNG were sicarios for the Viagras, a paramilitary gang from Michoacán who, for years, were allied with the Templarios and Cárteles Unidos before switching sides to join the Jaliscos.

Journalists and researchers have long criticized the concept of “cartels” as a misleading term pushed by the U.S. Justice Department in the 1980s to build cases while justifying U.S.-sponsored militarization — overstating the power of violent but unstable gangs by painting them as unified hegemons who threaten governments, rather than parasitic power brokers operating parallel to them.

Yet no one doubts the violence committed by Carteles Unidos, sometimes referred to as “R5,” and the CJNG, two sprawling paramilitary coalitions benefiting from shifting and at times overlapping protection agreements from Mexican security forces. Earlier this year, a volunteer group dedicated to finding disappeared people discovered a CJNG-run “extermination site,” a training camp operating in clear view of authorities where hundreds of victims were incinerated in homemade “crematoriums.” Both armed groups have been implicated in widespread massacres, disappearances, enforced recruitment, and the use of landmines and child soldiers — acts that, if the Mexican government recognized the violence as armed conflict, would constitute war crimes.

When El Guayabo’s population fled at dawn, according to multiple residents, gunmen for the Jaliscos shot sporadic potshots at villagers escaping on motorcycles. And then, one displaced resident said, “the rancho was completely empty.”

Tierra Caliente, the muggy shear of mountains that encompasses western Guerrero, the southern end of Mexico State, and the southern lime plantations of Michoacán, has been known for decades as a refuge for organized crime networks. The “Hot Land,” as its name translates in English, is notorious for wars between shifting alliances of government forces, cartels, and “self-defense” groups — which have intensified since the first major operation of the U.S.-backed drug war was launched in Michoacán in 2006. El Guayabo is just one of a string of villages in the region’s expanse of lime plantations convulsed by years of warfare.

For the first half of 2025, the campesinos in El Guayabo and nearby El Alcalde barricaded themselves in their homes while listening to the devilish rattle of gunfire in the darkness outside. Some families fled one by one in a slow trickle, their nerves shot from suffering abuse at the hands of armed groups while waiting for the next gun battle; others, trying to hold on, escaped in mass displacement episodes. Some people fled from El Alcalde to El Guayabo. Sleeping was close to impossible, one resident said, as they listened to the firefights while “waiting for sunrise to see if the government would show up.”

Government forces — well-equipped, well-trained, supported by U.S.-supplied Black Hawk helicopters, and frequently benefiting from close relationships to U.S. security agencies — have long exerted overwhelming military superiority over cartel gunmen when engaging them in direct clashes. But on most mornings, residents said, their hopes went unanswered. In February, the military installed an Inter-Institutional Operations Base, a multiagency outpost hosting soldiers for the military and National Guard known as a “BOI.” But firefights only intensified in the months after their arrival.

On July 16, as the gun battles reached a fever pitch, the entire population of El Guayabo fled.

One displaced resident, who, like all desplazados interviewed for this story, requested anonymity for fear of retaliation, remembers the helpless terror of waiting inside flimsy homes while listening to the cacophony of automatic and semi-automatic assault weapons less than a mile away. The houses — made from concrete, wooden walls, and thin metal roofs — were hardly reassuring shelters against a bomb or bullet.

“Imagine how we felt being in a house with sheet metal,” they said. “It was all so terrible, we were so afraid.”

No one went unscathed by the violence. The constant stress of listening for the devilish hornet’s whine of drones gave children anxiety. A woman heard a drone and dove under a mattress with her crying grandchildren seconds before a shrapnel-laden bomb exploded on a nearby roof. Over a dozen residents told me that soldiers who were stationed in El Alcalde, less than half a mile away, almost never intervened in a month of hourslong firefights.

They had spent weeks listening to nearby gunbattles, but by mid-July, the proximity of the fighting became unbearable.

“They’ve made it down,” a man says in a video shared on Telegram from July 16, referring to the fact that armed groups had descended from the hills, fighting in the semi-forested lime plantations and homes surrounding the village.

“It got uglier then, so we all decided to get out at the same time,” an El Guayabo resident told The Intercept.

When they returned at the end of the month, a man in his 50s, whose wooden home was riddled with gunfire, broke down in tears after seeing several of his chickens had died because he was unable to return to feed them. Some had been able to go back during the dawn hours to feed their animals, though they couldn’t stay long. “No one sleeps here anymore,” a resident said.

A man walked me through his house to where his corrugated metal roof was blown up by a bomb dropped from a drone, his windows and the windshield of his truck shot out too. The ground, Zepeda recalled, was “carpeted with bullets manufactured in the United States.”

The sicarios never lacked for ways to replenish their ammunition. Armed groups now turn to “WhatsApp and Telegram groups dedicated to firearms transactions operate much like online marketplaces,” said Romain Le Cour, a gun violence investigator and senior expert at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. “Similar to Amazon.”

Bullets for the same military-grade assault weapons lined up on the walls of gun stores in Texas, Missouri, or Illinois, could, within days, end up on the floor of a devastated living room in a rural, war-torn village like El Guayabo.

Pressed into the back of the dull bronze .50 caliber shell was a simple headstamp: LC19. The shell was one of hundreds scattered in the street before a devastated home, whose owner invited us inside as they examined the discarded military uniforms, the broken windows, and the cartridges scattered among stuffed animals and childhood school photos knocked off the wall.

“LC” is the marking for Lake City Ammunition in Independence, Missouri: built by Remington in 1941, run by Winchester, and owned by the U.S. Army. “19” is for the year it was manufactured. Thanks to the war on terror, according to its own government website, the factory’s modernization efforts brought its annual production capacity to 1.6 billion rounds a year, making one of the largest ammunition factories in the world.

The headstamps of the ammunition in El Guayabo corresponded to the photos of munitions from the Lake City factory available on the websites of gun brokers and enthusiasts, as well as a New York Times investigation from 2023. According to Bloomberg, the Pentagon has shipped hundreds of thousands of Lake City rounds to the Mexican military.

Jim Yurgealitis, a weapons expert and retired senior special agent with over two decades of experience conducting and participating in weapons trafficking investigations for the ATF, confirmed for The Intercept that the .50 bullets with the headstamps LC19, LC22, and LC23 were all produced at Lake City Ammunition.

Yurgealitis said that the round labeled “FC 5.56 18” may have come from Federal Cartridge, an ammunition manufacturer that operated Lake City in 2018, though he couldn’t say whether it was produced at the Army plant or at Federal’s private facility in Minnesota. Yurgealitis also confirmed that a 5.56 shell with a NATO insignia above the headstamp “LC24” came from Lake City.

Though munitions from Serbia, Sweden, and possibly South Africa were scattered among the destruction in El Guayabo, Yurgealitis, who reviewed a full list of the ammunition The Intercept discovered, pointed out that “none of the ammunition on that list hasn’t been available on the U.S. commercial market at least at some point.”

Lake City did not respond to The Intercept’s requests for comment. Neither Winchester, the operator of Lake City; Olin, Winchester’s parent company; nor Federal Ammunition responded to The Intercept’s formal media requests. The Intercept was unable to contact a media representative for Federal through two customer support numbers.

Coveted by gun enthusiasts for their military quality and armor-piercing capacities, bullets from Lake City, whose operations are overseen by the U.S. Army’s Joint Munitions Command, have also been used by mass shooters. In 2015, the ATF sought to ban the production of “green-tip” armor-piercing rounds — the Times investigation pointed to Lake City’s production of 5.56 green-tip rounds for AR-15s — but immediate pushback from gun enthusiasts and Second Amendment hard-liners in Congress led the agency to abandon the effort. The factory has a colossal production capacity — churning out over a billion-and-a-half rounds a year — thanks to the post-9/11 symbiosis between the U.S. government and private ammunition manufacturers, who keep machines running, ready to meet wartime demands. Lake City’s government ownership means the company enjoys minimal transparency, while Winchester, valued at over $500 million last month, profits.

In 2021, the Mexican government filed a historic lawsuit against seven U.S. firearms manufacturers and a wholesaler, seeking $10 billion in damages for allowing assault weapons to end up in the hands of cartels. The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously struck the case down in June, on the basis that the companies can’t be held accountable if their weapons are misused. A second lawsuit filed against five Arizona gun stores in 2022 is still working its way through the courts.

For the lawyer David Pucino, an anti-gun violence advocate at the Giffords Center who helped write an amicus brief to support the lawsuit, the already weak regulatory framework will only be made worse by Trump’s planned ATF cuts.

“It’s essentially catastrophic,” Pucino said. He added that changes could bring about “a massive rise in the vector of trafficked guns,” which will have ramifications for years to come.

The ATF is already a neglected institution whose budget allocations haven’t corresponded to the sheer scale of weapons trafficking, said Cecilia Farfán, the head of the North American Observatory for the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime who has investigated weapons flows from the U.S. to Latin America. In 2023, for example, there were at least 78,000 gun dealers in the U.S. Before the cuts, the ATF only has 800 investigators charged with investigating reports of straw purchase buyers.

“They don’t have a lot of resources,” Farfán said. “They haven’t seen themselves as an agency that can collaborate with other institutions; they work with very little.”

The ATF’s work has fallen short in the past. Between 2009 and 2011, for example, ATF agents in Arizona allowed cartel straw buyers to purchase nearly 2,000 assault weapons under the pretext of tracking them to their sources.

The ATF did not respond to The Intercept’s phone calls.

One former investigator for the ATF emphasized that the agency has a “very vital role in terms of their monitoring of the gun industry” but that “they’re already overwhelmingly understaffed compared to the amount of (gun brokers) out there. … Some gun stores get one inspection a year, some get an inspection every five years.”

Pucino agreed that the soon-to-be-slashed ATF inspectors are “essential” for tracing the flow of these kinds of munitions to criminal groups, helping educate gun brokers so they can better recognize — and report — straw-man buyers for trafficking networks. Without inspectors, he said, it’s close to impossible to recover guns once they make it out of shops.

“There are extremists who want no gun laws at all and an industry that wants to maximize profits,” Pucino said. “The suffering of Mexican people is not a consideration for those who are establishing policies.”

If you only follow Trump’s tweets, you could be forgiven for believing the U.S. has long been at the precipice of war with Mexico. “They are now designated as terrorist organizations,” he said of the cartels in January. “Mexico probably doesn’t want that.”

Yet the erratic saber-rattling has coincided with a quiet consolidation of security coordination between the two countries. Less than 24 hours after the Trump administration’s first controversial strike on a boat in the Caribbean, Secretary of State Marco Rubio met with Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum in Mexico City. “There’s no other government that’s cooperating as much with us in the fight against crime as Mexico,” he said. (Last month, a Reuters investigation revealed how the CIA for years secretly coordinated with elite Mexican military units.)

In September, Mexican and U.S. authorities unveiled “Mission Firewall: United Against Firearms Trafficking Initiative,” a “historic” plan to intensify crackdowns on southbound weapons trafficking.

The Trump administration promised to intensify inspections at the border, while the Mexican government will expand the usage of a surveillance tool called “eTrace,” a ballistic tracking technology that has been available to the Mexican government since at least 2008. “We’ve never achieved something like this,” Sheinbaum said.

The official at the General State Prosecutor’s Office in Apatzingán told The Intercept before the announcement that questions regarding ongoing investigations into weapons trafficking networks and displacement are managed by federal investigators.

“We work with the U.S., but we just do training and workshops with U.S. agencies in Morelia (the capital of Michoacán),” the official said. “The people who coordinate directly with U.S. agencies are the federal prosecutors.”

When I went to the office of the General Prosecutors for the Republic, a prosecutor declined to comment on the basis of “secrecy.”

In February, after Trump announced punishing tariffs, and again in August, after the directive regarding the use of unilateral military force in Mexico was revealed, Sheinbaum’s administration carried out two highly publicized, but legally contested, mass extraditions of 55 narcos to the United States. Targeting individual drug traffickers has long been discredited as a policy for reducing violence, one that runs the risk, instead, of exacerbating warfare. But it remains at the heart of the Bicentennial Framework, a tough-on-crime plan the two countries share. The framework’s implementation has coincided with the growth of enforced displacement and enforced disappearances — and the most violent period in the country’s history since the Mexican Revolution.

In El Guayabo, soldiers arrived with an Ocelot armored vehicle and a Humvee on July 30 and installed a BOI, the same kind of outpost erected in El Alcalde in March. Residents said the soldiers did, on several occasions, engage the sicarios in early August, a period when the combat between armed groups receded into the mountains above the village.

Despite the lull in fighting, residents couldn’t shake the fear that they would be abandoned to the whims of conflict yet again. They were well aware of the selective policing that’s typified the government’s response to war in Tierra Caliente: Security forces leave once media and political attention drifts away, opening the way for the return of criminal groups — who the government won’t confront in time, if at all, to prevent mass displacement episodes.

“It’s important to remember,” the official from the General State Prosecutor’s Office told me, “that what happened in El Guayabo is an isolated act.”

When I went on July 30, the residents who had returned were packed into family members’ homes or living week by week in overpriced hotels or rentals. Unable to tend to their lime fields, they’re out of work. “My parents can’t even get their medicine anymore,” one man complained. Though around half returned with the deployment of a contingent of soldiers to the village, the others stayed away.

“The people are still afraid, because [the armed groups] are in the ranch just above us,” one resident from El Guayabo told me. In the weeks after they returned, every now and then, they could still hear gunfire in the hills.