Despite being middle-aged, and far from a “maiden,” I wanted to reclaim my maiden name.

When I was in my 20s, the idea of marriage seemed constrictive. We were filling out the application for our marriage license in a county clerk’s office when I found out my future husband wanted me to take his last name. It was something we had never discussed, but he had assumed. He quickly realized there was no way I was going to budge. So he came up with a solution that he claimed would satisfy both of us, explaining, “If you hyphenate your name you can go by either name.”

He worked as a job recruiter, so he “knew how things worked in human resources.” This was 2001, pre-iPhone, and I couldn’t pull up Google to fact-check. I also didn’t want to hurt his feelings. I also wanted him to feel loved. I hyphenated my name.

Advertisement

A decade later, I’d be widowed with two young children and a hyphenated name. When my husband passed away, I decided to keep my married name on my official documents until my youngest turned 18. I had continued to use my maiden name professionally and socially, even when my husband was alive. Still, when you sign an official government document claiming to have a new name, that identity follows you.

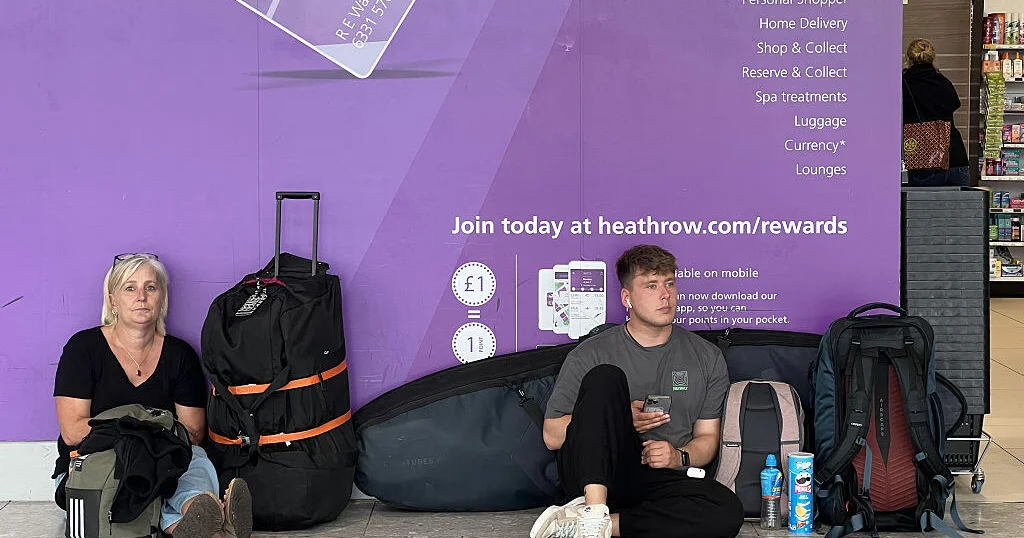

I had issues filing taxes and other official paperwork. I also found myself begging to be let on to planes when the name on my plane ticket didn’t match the hyphenated name on my passport and license. (Either because someone else bought the tickets or my computer autofilled the name on my credit card, which I never changed.)

TSA never agreed and I had to be given new tickets, which almost made me miss several flights. Ironically, one of my main motivations for keeping my married name was worry that having separate names might pose an issue when my child and I traveled.

Advertisement

Then, a few years ago, I started a new job, where they issued me an email address with my hyphenated name. I reached out to HR, and they informed me that they use the name listed on an employee’s Social Security card to set up the email. If I wanted to get the hyphen removed from my email, I’d have to get a new social security card with the name change.

Although my youngest wasn’t yet 18, I decided it was the time to go back to my maiden name. I had shelled out piles of cash and time on therapy to help me handle the loss of my husband, but nothing prepared me for the abusive process a widowed woman must endure while attempting to remove a hyphen and married name from government-issued identification.

The Social Security card was easier than I expected. I went to the Social Security office and presented my husband’s death certificate and our marriage license, and while the clerk initially told me this wasn’t enough documentation to change my name back, he eventually issued me a letter stating that my name was now Alison Lowenstein, and that I’d have a new card within a few weeks.

Advertisement

Getting my name changed on my passport was a bit more complicated. The woman at the office said I only had to send a copy of the letter stating that the Social Security office had updated my name, and I’d be issued a passport under my new old name. Instead, I received a letter from the passport office that they were holding my documentation until I provided additional information about my name change.

I sent a letter back via registered mail detailing that my Social Security card had my maiden name and included both the original marriage and death certificate. I hoped this would work, and it did, but none of my documentation was returned with my new passport.

Months later, when there were rumblings about needing a REAL ID to travel domestically by plane. I knew I had to get a new copy of my marriage license to bring to the DMV, so I could apply. As I sat in the county clerk’s office waiting to get my marriage license reissued, I looked at young couples filling out their paperwork to get married and had the urge to warn them that changing your name was a decision that was apparently more permanent than marriage.

Advertisement

My last stop was the DMV to apply for a REAL ID. I walked in with my Social Security card, marriage license, passport, and my husband’s death certificate and handed it to the clerk.

“You need to get a divorce,” the straight-faced worker at the DMV instructed me while he held my husband’s death certificate.

“Is that even possible? I’ve never heard of a post death-divorce? And I never wanted to divorce my husband.” I teared up, but that’s par for the course during a several-hours-long DMV visit.

Advertisement

“You can’t change a name without a divorce decree,” he said confidently.

I asked if I could speak to someone else. The clerk called for his manager, and she reinforced that the clerk was correct. To change back to my maiden name, I needed the required document — a divorce decree.

So why is a divorce decree on the list of official documents for a name change but a death certificate isn’t? I posed this question with the clerk and manager at the DMV. The clerk replied, “How do we know you were even married to this guy?”

I showed him my marriage license, to which he replied, “When he died. How do we know you were married to him when he died?” I wanted to yell, “Then I would have a divorce decree,” but I was too teary-eyed.

Advertisement

Eventually, the manager came up with one alternative to a mythical lawyer who specializes in post-death divorces: “a court-ordered name change.” But she warned me this was both costly and took a lot of time to get.

The court-ordered name change had to be requested at civil court. There is a sign on the stained Plexiglas window at the name change counter that warns that the process might require multiple visits. To get your name changed, you need a notarized multi-page application, an official birth certificate, a laundry list of other official documents, and 65 dollars in cash or a money order. You need to have exact change or they will not accept the payment. They claim it takes 60 days to process.

At first, I was turned away because I only had a copy of my birth certificate and had to order an “official” one. Fortunately, once I returned with all the documents, it was processed and a month later I received a congratulatory email that a judge had ruled that I can use my maiden name. I had to bring $6.00 (in exact change) to pick up the court-ordered name change. Thankfully, one no longer needs to actually see a judge to complete the application.

Advertisement

I spent the two hours waiting for my number to be called at the DMV worrying that once I reached the counter, the clerk would alert me that there was yet another document to acquire or task to complete in the nightmarish scavenger hunt that I had to partake in to use my maiden name.

Maybe all this sounds like a series of minor inconveniences, but it bothered me that I needed to jump through hoops and even go through the courts to use the name that was listed on my birth certificate.

I was relieved to find out that presenting the clerk with the court-ordered name change enabled me to finally get a REAL ID. However, the irony that the REAL ID, a form of identification birthed from the Patriot Act, is “real” but a death certificate isn’t a real enough document to allow a widow to change back to her maiden name on the REAL ID wasn’t lost on me.

Advertisement

Back in April, when I was in the thick of this process, the SAVE Act (Safeguard American Voter Eligibility Act) passed in Congress. Although it still needs to pass in the Senate, the SAVE Act changes the identification needed for voter registration. If your last name is different from the one on your birth certificate, additional documentation will be needed. In April, I also worried since we were on the cusp of needing the REAL ID to fly, that one day soon, we might need one to vote. The SAVE Act threatens to disenfranchise Americans without access to documentary proof of citizenship, but it could also make it harder to vote if you’re a married woman or anyone else who has legally changed their name.

I’m happy that at the end of this yearslong journey, I finally have my maiden name on all my official IDs. Yet, I’m also left with the memory of this exhaustive process. Proving that your name was changed because you’re currently married or were previously married is not a simple process. Tracking down a marriage license or ordering a copy of your birth certificate takes time and is always accompanied by fees.

20 Years OfFreeJournalism

Your SupportFuelsOur Mission

Your SupportFuelsOur Mission

For two decades, HuffPost has been fearless, unflinching, and relentless in pursuit of the truth. Support our mission to keep us around for the next 20 — we can’t do this without you.

We remain committed to providing you with the unflinching, fact-based journalism everyone deserves.

Thank you again for your support along the way. We’re truly grateful for readers like you! Your initial support helped get us here and bolstered our newsroom, which kept us strong during uncertain times. Now as we continue, we need your help more than ever. We hope you will join us once again.

We remain committed to providing you with the unflinching, fact-based journalism everyone deserves.

Thank you again for your support along the way. We’re truly grateful for readers like you! Your initial support helped get us here and bolstered our newsroom, which kept us strong during uncertain times. Now as we continue, we need your help more than ever. We hope you will join us once again.

Support HuffPost

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

According to a 2006 survey by the Brennan Center, only 66% of voting-age women already have a document that proves citizenship with their current legal name. I was fortunate to have the energy to undergo this process and to be able to afford the charges, but there are many women who can’t. Unfortunately, there is a possibility that one day these minor inconveniences could become a barrier to their voting rights.