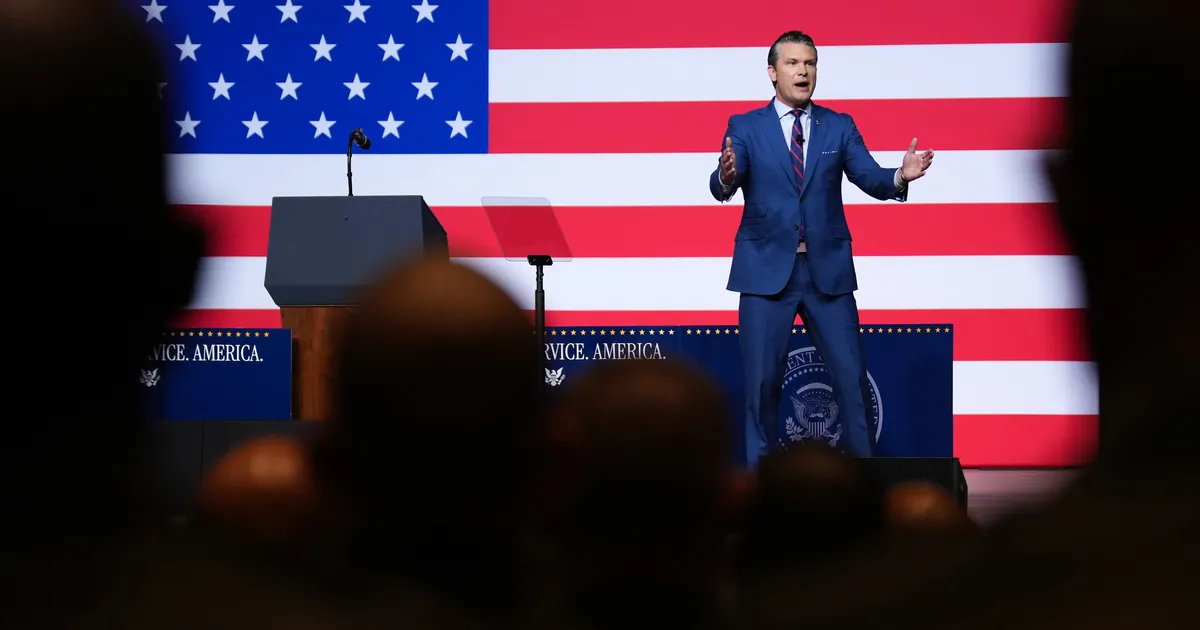

Defense secretary Pete Hegseth convened an unusual meeting earlier this week. Hundreds of top military commanders flew in from around the world to converge on Quantico at Hegseth’s orders. There, the former Fox personality and National Guard veteran postured in front of an enormous American flag and lectured his audience on grooming standards and more. Troops will have to meet a “male level” for physical standards, and there would be no more “fat generals.” If women cannot meet those standards, he said, “so be it … That is not the intent, but it could be the result.” But there’s no reason to take Hegseth at his word. He’s railed against women in combat roles for years, and this week, his speech betrayed an obvious fixation on gender. “I don’t want my son serving alongside troops who are out of shape or in combat units with females who can’t meet the same combat arms physical standards as men,” he said.

As journalist Jasper Craven reported in a recent piece for The Baffler, Hegseth has defined himself in opposition to women since he was an undergraduate at Princeton. According to a friend who knew Hegseth during his time in ROTC, the future Pentagon leader feared women “didn’t have the ability, if he was shot, to pick him up and carry him off the battlefield. That rubbed him the wrong way.” A hypermasculine bravado would later shape his time in public life. Hegseth has shown a particular reverence for special operators, defending some against accusations of war crimes, and he complains, often, that “woke” standards are weakening the military. Although Hegseth’s military career “was not especially remarkable,” Craven wrote, he expects his sons “to join the military — specifically, to become certified killers, as Navy SEALs, Army Rangers, or Green Berets.” During his confirmation, a New Yorker investigation uncovered a pattern of sexual harassment at Concerned Veterans for America when Hegseth was the leader of the conservative group. Earlier this year, the New York Times reported that a woman had accused Hegseth of rape. (He reached a financial settlement with the woman but denies the allegation.)

After Tuesday’s meeting, I spoke to Craven about his reporting along with Hegseth’s latest speech and gender obsessions, and how they are enabled by a pervasive culture of impunity.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

At the Quantico meeting, Hegseth rehashed some old fixations. He’s consumed by grooming standards and “fat troops,” as he put it. Why do you think this is such a priority for him?

I think that Hegseth from an early age really embraced this old-school GI archetype and all of the trappings and the image that goes along with it. Obviously, he grew up in the immediate shadow of Vietnam and the Cold War, but he preferred to obscure those military failures and reached back to World War II and the white-male GI whose successes saved the world from fascism. So there’s not a whole lot of deep thinking that accompanies that aspirational ideal for Hegseth. It’s really about the trappings, the image, the strength, and markers of old-school patriarchy.

Part of that stems from the fact that the wars Hegseth fought in Iraq and Afghanistan had no deep moral center. So all he could really do is glom onto this image, being the GI that Americans would still salute and recognize based on their uniform even though the wars may have been corrupt. That’s all Hegseth has had to hang onto, and he’s embraced that very deeply. Partially to squeeze valor out of it, but also to support his darker ideology, which revolves around deep misogyny and racial prejudice.

Who is most affected by Hegseth’s new grooming standards?

Black troops can develop a skin condition called pseudofolliculitis barbae because of frequent shaving, and in recognition of this ailment, the military relaxed grooming standards so they didn’t have to shave all the time and have these painful flare-ups on their faces. This is a way to expel Black troops from the force and hopefully, in Hegseth’s mind, bring in white ones. But it’s also a way to create more discipline and a more regimented culture. It smooths a path to create loyalty, to make it such a punishing environment that expressions of individualism are nonexistent. It may sound small, but it primes one to follow orders blindly.

It strikes me too that Hegseth is most immediately recognizable to many Americans as a performer, a television host. Can you talk about the affect that he projected during his time in his public life and how that shapes his affect now that he’s Defense secretary?

Hegseth, by all accounts, had a rather unremarkable military career. I think that it’s no mistake he hustled hard to get into the 101st Airborne, which had just been depicted in Band of Brothers when he signed up. He wanted a battle story, but he wasn’t able to succeed on that front. And then he spent a lot of time at home trying to agitate for the Iraq War’s continuation, which was hopelessly unpopular with the American public.

So he’s often reinvented himself. On Fox News, what Hegseth came to embrace was the mentality of the special operator and the bravado of the special operator, the machismo. But I think he was so desperate for that recognition that he became more and more bellicose and started to undermine military norms that he at one time probably embraced. He started to throw military justice out the window. You can see that with his defense of numerous war criminals. He came to theorize that blood and violence are the work that the military does well.

He obviously would not be the first person to seek a military career in the pursuit of a deeper purpose or meaning. But what military service means to him is not necessarily what it’s going to mean to other veterans, like my husband, who served in Iraq. Is there anything striking or unusual about Hegseth’s perception of himself and his time in the military, compared to other veterans and servicemembers?

The military understands what young people want and promises them those things, whether it’s community or identity or meaning. So there are those big, bold promises, which also include economic elevation. Oftentimes, there is selflessness wrapped up in all of that. The American military is sort of the only real path for public service. A lot of people join because they genuinely want to help this country, but they see very few other options.

In Hegseth’s case, there is the fact that he, more than most, always seemed to define himself against women, as if his own identity could only be secured through the submission of women. That speaks to a hegemonic military archetype that has been studied at length by academics. To him, he really wanted this patriarchal status, and he wanted a strength that could only be assured by women being subservient, weak, and unable to sort of meet his level. So he was really clinging to this old idea about what it means to be a man and how the military validates that. When the military didn’t do that, when the wars he fought ended up being the ones where women were first promoted and elevated in meaningful ways, and where women showed that they could meet men on the battlefield with strength, it completely discombobulated him and is still wracking his psyche to this day.

I’m glad you brought up gender, because that brings us around to the piece that you wrote for The Baffler and also to his speech. He said something this week that is familiar if you’ve read his books or listened to him talk, and that is his plan “to hold troops to the highest male standard, and if that means no women qualify for some combat jobs, so be it.” What’s the history of Hegseth’s rhetoric here?

Well, there is a long history of women serving in the military. There is also an equally long history of the military violently cracking down on the perception that their status is being impinged upon or circumvented by women. So that’s the context for Hegseth entering the service. But the “War on Terror” was sold to the American people with many false lines, and a particularly powerful one was that the war would elevate women in the Middle East. Alongside that, with the military realizing it faced bad optics, it opened up the ranks to women in new ways. It was also fighting a guerrilla war where women, no matter their position, were exposed to combat even if their titles didn’t specify or allow them to be facing those conditions.

You can tell through Hegseth’s books that he became deeply offended and that his own shaky self-conception was rocked very hard when a number of women, including Leigh Ann Hester, whom I mentioned in my piece, demonstrated real valor on the battlefield. So Hegseth has been throwing up all of these illegitimate or sort of warped talking points on Fox, and in his books, about women, who are not actually not as strong as men and can’t serve in these cool operator or badass roles in the ways men can.

Beyond that, the insinuation is that it was actually women who lost these wars, that the so-called Department of War was not lethal enough during the global “War on Terror” largely because of quotas for women and minorities. That’s what lost the war. Not the fact that we repackaged Vietnam War tactics and expected an outcome other than failure. It’s classic, in the sense that many veterans are forced to try to justify their conflict and explain away the failures. Many point in the right directions, to decisions by the officer class or the commander-in-chief. Hegseth has chosen to place the blame on women.

During his speech, Hegseth said that he was liberating his audience to be “apolitical, hard-charging, no-nonsense, constitutional” leaders. “Apolitical” really stands out in that sentence, because it is obvious that he’s not apolitical in any meaningful sense. Is that a new turn of phrase for him, and how does it fit into his ideology?

He’s virtue signaling in hopes that it can obscure the fact that beyond all of the personal animus and misogyny that motivates him as a person, there is a larger political project at play. It can be very easy to sort of make fun of the speech we saw, and indeed, there was very little substance in what he said. It was about grooming, it was about fitness, it was about looking the part. But the larger political project here, I think, is to create a military that is loyal, not to the Constitution, not to the American people, but to the president and to Hegseth.

Should Trump try to stay in power beyond his second term, he will need the military to help him. I think that there is probably a quiet understanding between the both of them that these four years need to be laser-focused on pushing out officers and enlisted who may not agree with them and replacing them with an officer class that would use the levers at the Pentagon to engage in some sort of military-style coup. I know that sounds extreme, but there’s evidence uncovered by the House Select Committee that Trump was trying to do just that in the run-up to January 6 and that there were a number of crazed military loyalists installed in high-level positions right before shit went down.

I first learned of Hegseth when he was advocating for the privatization of the VA. Can you describe his earlier political work and his stance on the military’s social safety net?

Hegseth spent a number of years shilling for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but it was not a particularly successful project in terms of public opinion. He pivoted from war advocacy to the Department of Veterans Affairs, working for a Koch-backed group with a libertarian mission of privatizing the VA. Hegseth was highly effective in promulgating a misleading argument about the VA. He said that it is corrupt and overstated wait times and the terrible quality of its care. In five or six years, he and his group were able to successfully push a series of laws that gutted labor protections for VA employees and led to thousands of firings during the first Trump administration, a total prelude to DOGE. There were thousands of illegal firings happening in the VA thanks to legislation Hegseth advocated for in 2017. None of that got much traction in the press.

Hegseth probably learned a number of lessons through that work, including the fact that his charisma could go a long way and could be effective at reshaping an institution like the Department of Veterans Affairs. He also built contacts in Washington and developed a relationship with Trump, and he was able to push a misleading message about the VA, which likely emboldened him in a way that you can see now with a number of Pentagon policies. Some are silly, but there are also a lot of really damaging and potentially dangerous ones.

While Hegseth was performing in front of his flag officers, the National Guard was picking up garbage in Washington, D.C. To the Trump administration, which includes Hegseth, the military is a blunt instrument and a way for them to punish domestic enemies. Based on your reporting, can you provide any insight on how active-duty servicemembers and veterans perceive the administration’s actions?

It’s really hard to get a full picture of how the military is thinking about Trump and how they’re thinking about this use of military force domestically. I’ve been speaking to a lot of sources who are genuinely very angry and offended and worried about this weaponization of the military against the people. That being said, Trump won a historic margin of military veterans in his 2016 campaign, a much higher number than John McCain received. That number only strengthened in 2024. Some retired generals condemned Trump after January 6, but many endorsed him three years later.

A lot of people say that the military is reflective of the American population at large, and that’s true, though Trump is trying to change that. So obviously, there are a lot of people who don’t agree with his politics, which are in many ways unprecedented. Obviously, the National Guard in particular has been weaponized against the people before; Kent State comes to mind. But I think the question at the end of the day is whether this long-held rule in the military, to disobey illegal orders, will be put into action. One can argue that despite military brass repeating ad nauseam that troops can disobey illegal orders, it’s never really been a common action simply because there is so much retaliation when someone subverts the brass.

Were there officers at Hegseth’s speech who were pissed off to be there and probably offended? Absolutely. But they still got on a plane from Japan or wherever and flew to Washington and stood up and saluted him. So it’s just really difficult to tell right now where one’s deep moral code will kick in. For many years, they’ve been conditioned to follow orders and obey a very strict hierarchy. And Hegseth and Trump are at the very top of that hierarchy. Unfortunately, the main thing that officers with a conscience can do is resign, which I respect, but at the same time, it opens another slot for a new sort of loyalist to be put in.

I also see a fairly obvious contrast between someone like Hegseth and someone like Graham Platner, the Marine veteran who’s running to replace Susan Collins. They both served in the “War on Terror,” and they’ve reached wildly different conclusions about that war and what it means. How does the legacy of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan shape our political conflicts at home?

There have been many notable figures who’ve stepped forward from these conflicts and offered a biting critique of what went wrong and how American foreign policy failed. And some of those voices have been elevated, but the media has a very narrow definition of what it considers a troop worth lionizing, despite the fact that members of Veterans for Peace are out in the streets protesting about Gaza. There are lefty vets, which you’ve written about. There’s often an ignorance about veterans who have a different narrative or experience than the prevailing Pentagon talking points.

People like to take Hegseth’s service and jump to the conclusion that he was disillusioned by these wars and that he kind of represents this critical strain. Same with J.D. Vance. But I just don’t actually believe that’s true because none of their actions reflect that. And they’re not speaking articulately about it. It’s like the media’s putting words in their mouths. Yes, I think a lot of them are sort of disingenuously using the withdrawal in Afghanistan to attack Biden, but they’re not trying to stand up for anything or speak out against popular conflicts. They’re all agitating for conflict. That’s what it means to funnel weapons to Ukraine and Israel.

There are plenty of veterans who served because they wanted to get the G.I. Bill or because they had a selfless notion of what service should be. They really are disillusioned, and they can say that and they can speak powerfully about it, but also, the military isn’t their entire identity. And the military should never be someone’s entire identity. This country was founded upon deep distrust of the military and the concern that the soldier would be empowered to abuse the citizen. With all of this rhetoric and many of these veteran campaigns for office, the underlying message is that the soldier is superior to the civilian. And that should not be how our politics works, because it fuels toxic undercurrents in people like Hegseth, whose litany of egregious behavior, including alleged rape, has been obscured partially by his military record.

I want to close on this question of impunity. We haven’t reckoned as a country with the failures of the “War on Terror,” in my view. As Vance and Hegseth consolidate power and contemplate political futures that could bring them into conflict with each other, how should we think about our culture and how it’s enabled them?

There are ways to manipulate the voting body that Trump has pioneered and that people like Hegseth and Vance are studying very closely. Vance hasn’t figured this out or articulated this as much, but Hegseth understands how to posture himself as a veteran without needing to reckon with the failed wars or his own behavior, or the fact that he served alongside a unit that was nicknamed Kill Company and got ensnared in a war-crimes trial. There remains a deep, though diminishing, public well of support for the military, and it’s the last trusted agency in government. To some degree, it remains influential and appreciated because so much of American government has decayed so quickly. But not the Pentagon. They just got the first $1 trillion budget.

It seems like the last thing we can do as a country is to build bombs and send bombs. We can kill people. So the American public has been forced into these conditions where the military is what we’re good at, and I think that Hegseth can seize on that if nothing else.