Kubrick, Kendrick, Spike Lee, Beyoncé, Hype Williams, and Luca Guadagnino Have All Called on This Legendary Cinematographer

By Julian Kimble

Copyright gq

Malik Hassan Sayeed wanted to be an architect before anything else. From an early age, he was fascinated by the idea of using his own two eyes to alter space and, in a sense, reality. While he was a student at Howard University, Sayeed worked as an electrician and rigged lights at local shows as a card-carrying member of the local International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees chapter in Washington, D.C. His stint learning the technical aspects of production, in addition to his own interest in film and photography, has led to a career in the visual arts which has spanned over 30 years.

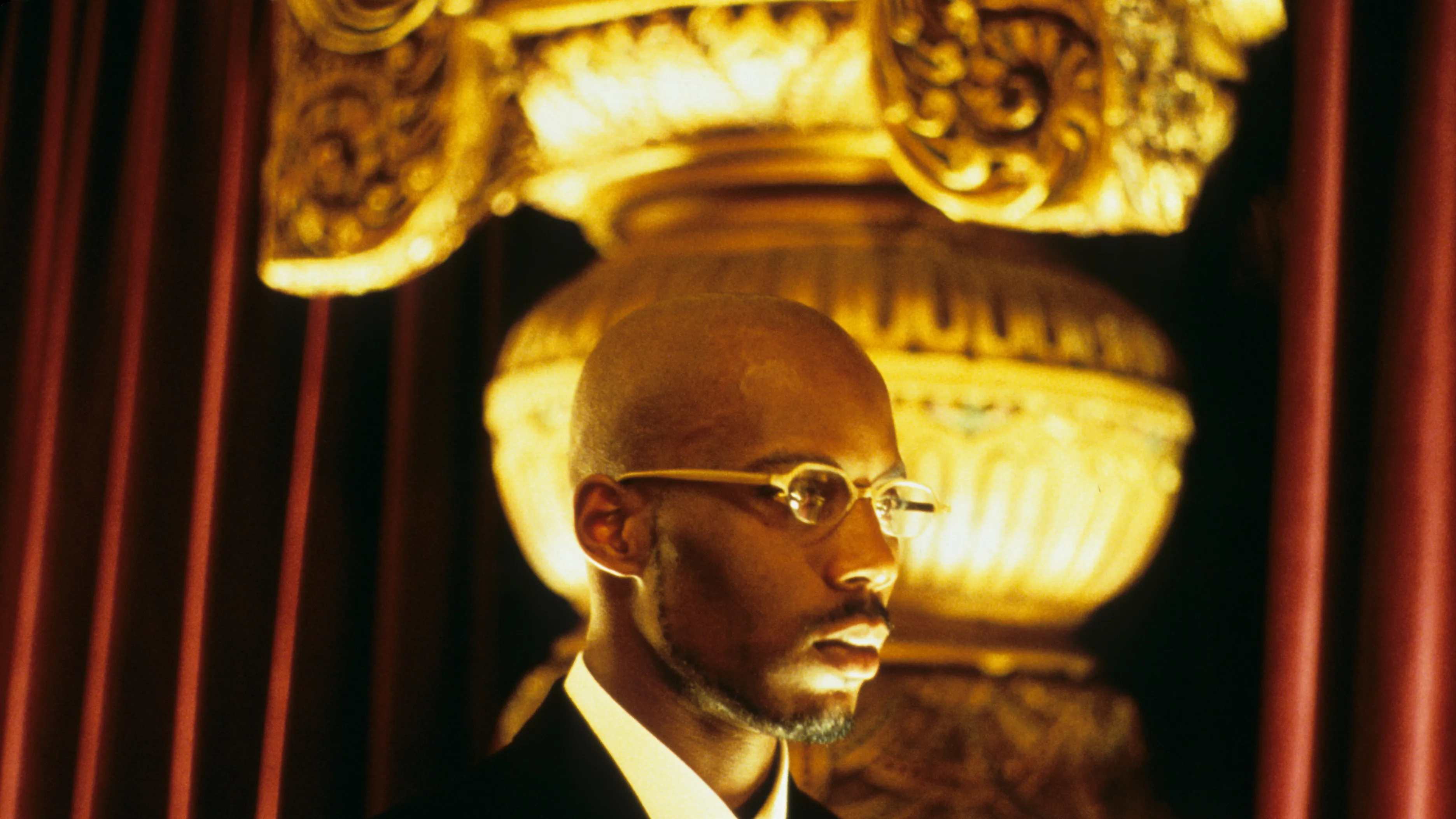

After finding a kindred spirit in Hype Williams, Sayeed helped the pioneering director define the style of hip-hop and R&B videos during the 1990s, before serving as the cinematographer for Williams’s lone feature film, Belly. And after receiving his first break on the set of Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, Sayeed followed in the footsteps of filmmakers such as Ernest Dickerson and Arthur Jafa, working with Lee as the cinematographer of Clockers, Girl 6, He Got Game, and The Original Kings of Comedy. “Hype is probably the most intimate working relationship I’ve had in my career,” Sayeed says. “Spike is probably number two.”

Sayeed has lent his perspective to videos for some of the biggest artists in music and worked behind the camera, in various ways, for visionary directors. He helped Williams’s lone film become influential and worked with the second unit on Stanley Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut, shooting the footage of New York’s streets that plays behind a walking Tom Cruise in the film’s “exteriors.” But after a long hiatus from the big screen, Sayeed has returned as the cinematographer for Luca Guadagnino’s Ivy League-set drama After the Hunt, which stars Julia Roberts, Ayo Edibiri, Andrew Garfield, Michael Stuhlbarg, and Chloë Sevigny. Aficionados of Sayeed’s style will see him all over it, from the use of a fisheye lens (a signature of his work with Williams) to an overhead tracking evocative of work he’s done on various projects, including The Players Club.

Sayeed, who rarely does interviews, recently spoke to GQ about his extensive career and return to feature films.

On getting the Malcom X gig

I did as much studying related to Malcolm as I could. Any books, anything I didn’t understand, I tried to figure it out. Even when I was working shows with the union, I would bring my books and my highlighters. I also came up during the era of music videos. The era you’re in helps determine where you can learn practically. For the generation before us, it was documentaries. If you look at Ken Loach, Mike Lee, and a lot of the guys who come out of the BBC documentary world, that’s where they cut their teeth. We cut our teeth in music videos. It was just promotion for the album, so we could do whatever in the beginning.

Pre-Malcolm X, I had hours of electrician experience on different productions. When I graduated from Howard, I applied to graduate school and didn’t get in. But because I was a young rigger, and one of few young Black riggers, there were tour managers who would come to town and look at me like, “You wanna go on the road?” I was offered to go with Whitney Houston and different people, but I just wanted to finish school. So when I finished, I got a call to go on the road with Bell Biv DeVoe, Keith Sweat, Johnny Gill, and Monie Love. That was the first thing I did out of school. Even though I knew I wanted to pursue film, I wanted to get that out of my system. I also learned how to do lighting design for theater while I was at Howard. During my gap year, I applied to NYU, Yale—which is kind of crazy because of the film we just did, which is set at Yale. That was when August Wilson was there.

I didn’t get into any of them and I thought that the money I made from the tour was what I would use to pay for graduate school. Instead, I bought an Arri 2c 35mm, which is like a World War ll camera or news camera that was meant to be like a tank. I loved that camera and shot whatever I could. I didn’t go to NYU, but I went up there and posted my information: “If you need a cinematographer, call me.” I thought a student would react, but another guy who didn’t go to NYU and was looking for a cinematographer found me and I did my first project with him.

All of these things are going on at the same time and I’m focused. My stepfather, who I’d lost contact with, was on the movie as a consultant. I felt like I was supposed to be on the movie. There was resistance, because it was a union job and I was in the union in D.C. But because Spike was seeing me and because he’d love to have someone like me working on the film in that department, he told the producers.

On what he learned while working on Malcolm X and how he developed a relationship with Spike Lee

I was a baby in even understanding how films were made at that level. I didn’t understand the practical side, so I was introduced to that immediately. And then just how robust each department is, it’s really amazing to see. Also, seeing inside of the cinematography department and the departments which fall underneath that: camera, lighting, and grip. Watching Ernest Dickerson and how he was managing both his ideas and the execution of telling the story, then how that played out on the ground. That was huge for me. I think taking all of that in was the biggest thing.

On working with Jafa on Crooklyn

If you’re moving forward and evolving, you have the potential to become a gaffer, which is the head of the lighting department. So I started gaffing for several people, mostly on music videos, sometimes documentaries. But the person I probably gaffed for the most at that time was AJ, who has a whole different life now, but was the cinematographer who shot Daughters of the Dust and is highly celebrated. Our relationship is on another level. [Filmmaker and longtime Howard professor] Haile Gerima recognized that we were on the same track, because AJ was ahead of me [at Howard], but he knew that we needed to connect. And then there were other people who recognized it who connected us. We connected on Malcolm X, because he was an operator and I was in lighting the department, then we were like this [wraps fingers together]. I’m the older brother in my family, but I had a desire to have an older brother. The two people who are the closest thing I’ve had to an older brother are Fab 5 Freddy and AJ, it’s that deep with him.

I worked with AJ a lot and he was doing really interesting projects. He introduced me to a lot of interesting people because AJ’s interesting [laughs], and his interests are encouraging and inspiring. So by the time we got to Crooklyn, we already had a body of work. You’re talking about rhythm, so when he got offered Crooklyn, I was already gaffing it in his mind. But, not so fast: the producers didn’t think I was prepared to be the gaffer. I thought I was, but they offered me the chance to be the best boy and brought in Reggie Lake. That was great because he’s such a beautiful soul. He was very accommodating to the reality of me and AJ’s relationship and he’s a veteran.

There was massive resistance from the New York local because of both Reggie, who’s from L.A., and myself working on this project. It was, on a certain level, irrational, but it was important. Trials are meant for purification. I struggled through it, but it was instrumental. It was more responsibility, and the best boy’s responsibility is unique because it’s very managerial on a certain level. You’re managing the crew and equipment, primarily, making sure everything is organized for that department to run in a fluid manner for the gaffer and electricians who are there. So I wasn’t as close to being on set with AJ, because I was managing call sheets and time cards.

On landing Clockers, his first feature film job as a cinematographer

I think it’s important to understand the context, because people might think it was some nepotism or DEI whatever—absolutely not. Again, I busted my ass. There are two people who I have so much reverence for because of their strength and courage. We could talk about Spike in terms of his work, which is in and of itself, but there’s another layer to his legacy that I know doesn’t get enough attention. It’s the amount of people, both in front of and behind the camera, that are in the business—who have careers and are able to take care of their families—because that man had the courage to recognize talent and want to work with people, even if they weren’t the big name. He wants to work with certain people when he recognizes it, both talent and energy wise. That’s important to your working environment, and I knew how valuable that was coming up in music videos. Way before Clockers, I was shooting, gaffing, and sometimes I was an electrician on bigger projects. In the very beginning, I was still going down to D.C. to work in the union when I had to. So I’m shooting as much as I can on 35mm; my refrigerator was half food, half film.

The second person was Hype. Me and Hype started together in the world of music videos, and we came up in the legendary Lionel C. Martin and Ralph McDaniels’s Classic Concepts. If anybody knows film in New York at that time, there were a few companies that were instrumental in doing most of the videos: Classic Concepts, 900 Frames, Paris Barclay’s Black & White Television, and Shoot ‘til You Drop. Lionel was probably doing the most work; all the main R&B groups, all the main rap groups. Hype came up doing graffiti and that’s how he got into art direction and comic books, but he had his own passion around directing. So he’s in the art department and I’m working in the lighting department. These spaces are beautiful because it’s like magnets: the people who are aligned will find each other. So, of course, me and Hype found each other. We’re both driven and we end up doing our first projects together. My first music video was Chi-Ali’s “Funky Lemonade” with Craig Henry. The second, which I did with Hype, was Erick Sermon’s “Hittin’ Switches.”

If someone gave us $17,000, we were like, “Wooo, let’s go!” We were so happy we got some money. What we ended up doing was pushing ourselves. One of the things we recognized about each other, and I don’t know how else to say it, but there was a standard for us that didn’t necessarily exist at the time. Our standards were over here, not what we were seeing in the beautiful space that was BET. We wanted to elevate. We were studying and learning, we had our North stars, and we were going hard. What came out of that was a body of work; now there’s a reel. Spike knew me as an electrician and gaffer: I’d gaffed some things with him leading up to Clockers because AJ was shooting some things with him and I was the gaffer. But he didn’t necessarily know me as a DP. What ended up happening was Lee Davis, who used to produce some of Spike’s short-form stuff back when Spike was doing the big campaigns for Nike and more.

There was a big commercial coming up—I can’t remember who it was for, but it was hockey related and might’ve been for ESPN. Robert Richardson was supposed to shoot it, and he was surging at the time because he’d done JFK and Natural Born Killers, he was killin’. Spike wanted to work with him, but I guess a film came up and he was no longer available at the last minute. They were looking for another DP and Lee asks, “Have you ever seen Malik’s reel?” I sent it to him and Spike was like, “OK, let’s give him a shot.” I was nervous, but I’d been shooting. I worked really hard on that and, praise God, we had success. He liked the piece and I was happy with the work I did on it. And then we ended up doing a bunch of stuff. We ended up doing some music videos for Crooklyn and I shot all of this b-roll; just out there by the Brooklyn Bridge by myself, swinging tilt lenses.

I think, at a certain point, you recognize that the youth is moving and you want to stay with it. So Spike was seeing that the youth was doing something and he wanted to stay youthful. He recognized that the music video side was an experimental state where we played around with different techniques and visuals that he was excited about. We did a bunch of that stuff, and come time to do the movie, this is where Spike—and this is just him being a soldier—asked me. I know what it means, in terms of pressure, to be in that position and say, “I want to work with this young cinematographer.” I’m so grateful for that courage. So, of course that meant I had to go all the way in.

On getting the shot in Clockers where you can see Harvey Keitel’s reflection in Isaiah Washington’s eye

Today we would do that in post, but I don’t think it would have the same effect. It’s such a difficult shot to do. Isaiah? Amazing. A lot of actors today wouldn’t want to sit there for that. I think we used a snorkel lens, which allows you to get that close. Those lenses are very slow, so you need a lot of light. And, remember, any kind of reflection needs a lot of light for it to show up. So we had to take all of that into consideration. We figured out how much light I would need, I probably got it wrong on the test—and that’s the time to get it wrong.

Harvey Keitel had to sit in that light and it actually set his hairspray on fire, to the point that it was smoking. He’s such a hardcore Method dude, because he was in the hot seat in the scene. There were a lot of moments like that in the movie where it was conceptual, and I had to get from the conceptual to the practical. It required a lot of testing from me to get there because we were pushing it, it wasn’t normal stuff we were doing. That required a lot of resources, a lot of lighting, and a lot of patience on a lot of people’s part.

On the difference between working on Clockers and Girl 6, his second film as Lee’s cinematographer

You’re in a different world in all of these films. We’re creating worlds, and this idea of realities shifting or being in different realities is foundational to my understanding of life. The first thing I wanted to be was an architect and I think it was because of transforming spaces and changing reality. We were in a different reality, because Clockers was kind of heavy. And then we go to Girl 6, which was a female-dominated space, so very different. I’m not normally in spaces like that, so that was probably the biggest shift between the movies. The darkness was very spooky—and by the way, a lot of people don’t know that the guy who plays the caller is Peter Berg, who’s a director now. He asked me so many questions about cinematography. So many people say they want to be directors, but when I go back to that time with him, he was asking me questions whenever he had a moment. I love to talk film craft with people, I’m nerdy in that way.

On the process of editing Wu-Tang Clan’s “Can It Be All So Simple” video with Hype Williams

I don’t know exactly what they didn’t like, but it’s like taking a picture. Most people don’t 100 percent like how they look in pictures. I didn’t do it, but even [“California Love”] the classic Mad Max video that Hype did for 2Pac and Dr. Dre—2Pac hated that video. As masterful as it was, they went and shot another version the next week with a bunch of girls around a pool. I didn’t shoot the first part of the Wu-Tang video, John “JP” Perez did. But I shot the pickups and some reshoots they had to do, so I went back out there and did that. That’s my favorite Hype video, because of the relationship between the visual and how the song feels.

There’s one Hype and I did with Mic Geronimo where we caught the vibe of the shoot on film. A lot of people don’t even know that song, but I think it’s the closest we got where the visuals feel like the music. But “Can It Be All So Simple”? Man, that’s a masterpiece of a track and when you get a track like that? Ooh, the responsibility of getting it right. We knew we couldn’t mess that one up. Hype is a master at understanding what’s gonna hit culturally. I don’t know if “hellish” is the word in the sense that it was tense, but Hype had it done and there was something they didn’t like, which creates its own kind of hell. And then, of course, you can’t forget the label’s input. That’s where the hellish part comes in, becomes sometimes their feedback doesn’t make any kind of visceral, expressive, or emotional sense. Sometimes it doesn’t even make business sense, it’s just a singular person’s opinion.

On his favorite collaboration with Williams

This is kind of like when my daughter would ask me, “Daddy, what’s your favorite color?” when she was young. I like color combinations. I don’t know if I have a favorite, because the journey with Hype is of kinship as creatives. We did so much together, experienced so much hardship, traveled so many places, ran into so many problems. Shooting is mostly problem solving. So in going through that with somebody, you just develop such a bond and I miss that guy. We don’t see each other that much anymore and I want to. Now, I will say, it’s probably Belly because of how intense it was, where we netted out, and how we privileged all of our creativity first, even though there were people fighting us. You wanna talk about hellish? That was a hellish experience.

It was so irrational that, if it didn’t happen, you wouldn’t believe it if somebody told you. If we had hidden cameras to capture everything that was going on, I think that would be bigger than the movie. It would be like the making of a movie that you can’t believe because of all the stuff that went on. I’m sure a lot of movies are like that, but this was definitely one. There are also layers to it: New York and Jamaica, which are very important places to me. I knew we had to get the Jamaica side right. One of my biggest pet peeves is when there are actors who aren’t Jamaican playing Jamaicans. They tried to do that with Belly. I tried to stay in my lane until the producers were involved and Hype was kind of lost, but that’s when I was like, “Oh, no no no. Hype, come with me. We’re gonna figure this out.”

So we went down there and I was determined to find somebody at a dance. As soon as we got in there, Louie Rankin walked right by us and I was like, “Yup.” He was already a legend. So we called him in and the rest is history.

On what he’s most proud of about Belly, all things considered

At a certain point, you have to stop caring what people think. It’s already hard enough trying to develop it, you have to be OK with failing. So for us on Belly, we were already in a flow state through the music videos, which, again, is why that was such a great space to work in. That was our practice. Belly was a culmination of years of work. Me, Hype, and [Director X], who was just doing storyboards for Hype, went to Jamaica and walked through the entire film, talking about things we’d done in the past, things we were interested in, and his vision for the film.

I will say regarding Belly’s story—and this is sad, but I have to say it: a lot of the places where it feels like there’s holes, that’s because the characters aren’t filled out. There’s story and exposition that needs to be in the movie for you to understand it from a human perspective. The best way to mess up a movie is to start cutting scenes. I’ve noticed this with a lot of films, especially Black films of that time: you’d miss the understanding of certain characters. I never understood why until I started working on some of these movies before Belly. They’d just cut scenes, but they didn’t feel like it was important to sell the movies. “Oh, this audience doesn’t care about that.” Well, they do care. The audience is robust and smarter than you think, so why lower the value? They did that on this film, and that was a big part of our fight. So if you’re missing it, it’s probably because it was there and got cut.

On what he saw in Ray Allen while working on He Got Game

You could see how much of a professional he is by way of who he became in the NBA. He wanted to get it right, so he was focused. I also don’t think he could believe it, so he was kind of in the moment. He reminded me of a lot of artists who we worked with for the first time who became huge. It’s all brand new, so there’s a different type of engagement and it’s really beautiful. Usually they have at least one big production meeting before the film where you go through the entire script and talk it through with all the departments. Anything that needs to be said by the director, in the macro sense, is said.

One of my favorite moments was when the person who did the visual effects in post-production asked a question about a scene where Ray was supposed to hit several shots in a row. One of them was a half-court shot and he didn’t think Ray could make it. He asked Spike this question so matter-of-factly, because he’d already worked it out as an effect in his head. And Spike didn’t understand his question, so he was wondering why we were talking about visual effects for the shot, because Ray Allen is making that. And he was like, “Really?” Even I was like, “Damn, he’s making that shot after the dialogue?” But man, getting out there with Ray Allen, we saw that this dude didn’t miss, even before he was the three-point champion. So we did the scene, he said the dialogue, he made the shot, and I was like, “Damn, that’s crazy.”

On working with Kubrick on Eyes Wide Shut

Again, being in the right place and knowing the right people put me in the position. He looked at my reel and said, “OK, let’s go.” He’s a cinematic hero; one of the brightest stars in my cinematic universe. So I just feel blessed to have been able to participate in that. Before shooting, it was daunting. But then once you get out there, you have to remind yourself: “Oh, you do this.” I think we functioned beyond just doing the shots for him. You have to realize, which I didn’t really understand that deeply at the time: I knew he hadn’t been in New York in years. He hadn’t seen New York; he didn’t know what it looked like, because things change. When I go to D.C., it blows my mind [laughs].

New York had changed, so what we ended up becoming was his way of seeing it in his latter days. It’s a city that was beyond important to him—it was his home, but he hadn’t been there in twenty-something years. He had an idea, in his mind, of what New York looked like, but you have to realize: this wasn’t the Internet age. So, we’re going out shooting all over areas of Manhattan—but some of it was over the bridge in Queens—and he’s building everything at Pinewood Studios. Because he’s so precise and meticulous around these things, the authenticity was critical to him. He wanted to have whatever he needed to build what he needed to build to fill in the background for the green screen stuff, but at the same time, I think he was interested in seeing what New York looked like.

We shot way more than what we intended to shoot. In fact, he would send us back to locations. We would shoot, process the film, dailies would go to him, he’d look at them and react, then tell us we either got it right or didn’t. But a lot of times, he’d be like, “Hey, pan to the left this time” or “Pan a little bit more to the right.” We didn’t get the shot right, he just wanted to see more. We became his eyes for seeing New York in his latter years, which I think is incredibly beautiful.

On working with Beyoncé on her “Formation” video and Lemonade film

Beyoncé is kind of the ultimate professional, and a prototype, I think, for what artists need to be in the world we live in now. She manages every layer of business, which I feel like you need to do. You don’t control anything you don’t govern, and I’m of the belief now that the more you exercise agency over these things that even go beyond what you signed up for doing, the more you’ll be able to apply yourself overall and to the things that interest you. The directors who are also producers are some of the most interesting directors I’ve worked with, because they can make decisions around priorities. “No, we’ll cut that and keep this because that’s most important.” Whereas a producer would just cut something because they thought it was superfluous.

I think you need to have that level of agency over all levels of what you’re doing in order to really affect the work. So yes, I’m in reverence of her and what she’s done with her career. But she also surrounds herself with amazing collaborators. That, in and of itself, is brilliant. It’s who she recognizes, like [“Formation” director] Melina Matsoukas, and they’ve had an incredible working relationship. It was amazing being with her in her process, and that’s the thing about being with creative people who value creativity and expression on that level. Process excites me, because any valuable process will be unique like a fingerprint. I think it’s important that people understand that. I was able to watch hers, which is amazing on all layers, but especially her focus on dance, movement, and how it’s captured. She’s a massive force.

On what he sees in Kendrick Lamar and Dave Free, and the experience of working with them

Dave reminds me of us when we were young. I think that’s why I’m enamored by him, because he has it and not everyone does. Vision is special because it’s connected to the now, it’s connected to the culture, it’s outside the box, and it’s broad. He gets it and I think it’s so incredible, because I feel a kinship because we started here in Compton. Kendrick is functioning on another level. AJ’s actually said this about Michael Jackson and Jack Johnson: if you look at their lives and careers, something was happening on a higher level—like, on an Orisha level. I’m starting to feel like Kendrick has some of that. There’s something about what he’s doing, I’m happy that he exists. Because he’s speaking to a generation that is hard to reach on a macro level, especially with all of the influences out here. He can hit like that and he’s pushing growth.

I got to work with him on something here in Compton for Reebok. That was cool because I was back home. That’s the thing about our communities: it’s beauty mixed with tragedy. And because it’s all wrapped up in the same thing, we sometimes want to throw it all away. But there’s all this beautiful culture here: there’s the mini-bike culture associated with the ‘hood, but there’s also some high-end creativity taking place.

On working with Jafa on Jay-Z’s “4:44” video

That was pretty much driven by AJ. Me, AJ, and Khalil [Joseph] had a film collective at the time called TNEG and he was interested in us working on his project. You could take us individually or you could take us together. It wasn’t for “4:44” at first, it was for another song that he was going to do with James Blake that I don’t even think made the album, which wasn’t finished. We went to the studio with Guru on Sunset to listen to some tracks and there was one in particular, because they didn’t want to release it. At the same time, AJ had just put out Love is the Message, the Message is Death. I think Jay saw that and was intrigued, and wanted to know if we could do something like that.

The approach to the song with James Blake would’ve been different. It was a song for his girlfriend or fiancée, apologizing for being as horrible as he had been, because he was with her before he was famous. You know how they say that when you get popular, you’re gonna change? Yeah, he changed, so he was becoming self-aware that he was harmful to her, emotionally. It was a pretty intense song, and as you know, there’s a lot of that on that album. When “4:44” came along, there were a series of discussions around doing it like Love is the Message, which is its own masterpiece. We were reaching for that, as it relates to the lyrics of the song.

On returning to film for After the Hunt and working with Guadagnino

I met Luca around the time Call Me By Your Name came out because we’re directors at the same company. He’d expressed an interest in working with me back then, I guess because the films I’d done in the past were very impactful on him as he was coming up as a filmmaker. I didn’t necessarily think this would happen, but then it came up. We ended up doing a commercial together, then he asked me to do the film. One of the reasons I haven’t done a film in a long time is because I wanted to be present as a father and husband. I realized, at a certain point, I wasn’t going to be able to do that the way I wanted to.

It became a timing thing: if and when the time was right, and there were several boxes I needed checked. These films have no life and we give our lives for them to exist. That includes sacrifices of time with our parents or children. So, it had to be something I felt was valuable. That was the first box. Number two, who am I making the film with? Can I be expressive in some way? Those boxes were checked and I’m really happy with what we did, especially the process. Luca is a master. I’m at a point in my career where I want to learn and I always have this fantasy of going back to school. It’s such a beautiful space, because all you’re there to do is learn and grow intellectually. This film is set at Yale, so we were in an academic space.

What’s interesting about Luca is that he didn’t study filmmaking. He went to school for art history and film theory, and he was a film critic before he was a filmmaker. He was also a food critic. And he’s a film enthusiast—it’s one thing to study film theory, but he’s studied the craft of the masters. His ability to recall their film grammar is incredible and very inspiring. What I recognized with a lot of his films is that they’re exercises in areas of filmmaking, and filmmakers, that he’s interested in. For example, Call Me By Your Name is clearly Éric Rohmer and French films of that ilk. But he also has his own visceral style that excites me. It was fun for me to work with someone like that, because there was a certain level of restraint that I loved and was important, I feel, because of my experience.

He wouldn’t storyboard, he’s very present in the moment. We didn’t shoot anything with tech scouting. Once we did rehearsal, he would just react. Here’s the other thing he did that was critical which I think young filmmakers should learn: If you want to have a voice and unique fingerprint in cinema, I feel like you have to become intimate in the editing process. Luca loves editing. He has a facility in his house. He kept his editor on set. And he’s in a flow state with it. He doesn’t cover scenes, he shoots the edit. It’s super economic, he doesn’t do a lot of takes. It allows you to move through things quickly and fluidly, but it’s helpful for the actors too. And Julia and Michael, oh my God, these are masters. They would just nail it on the first take and maybe do one more. I enjoyed watching them on set, and, of course, Ayo and Andrew—the young guns.