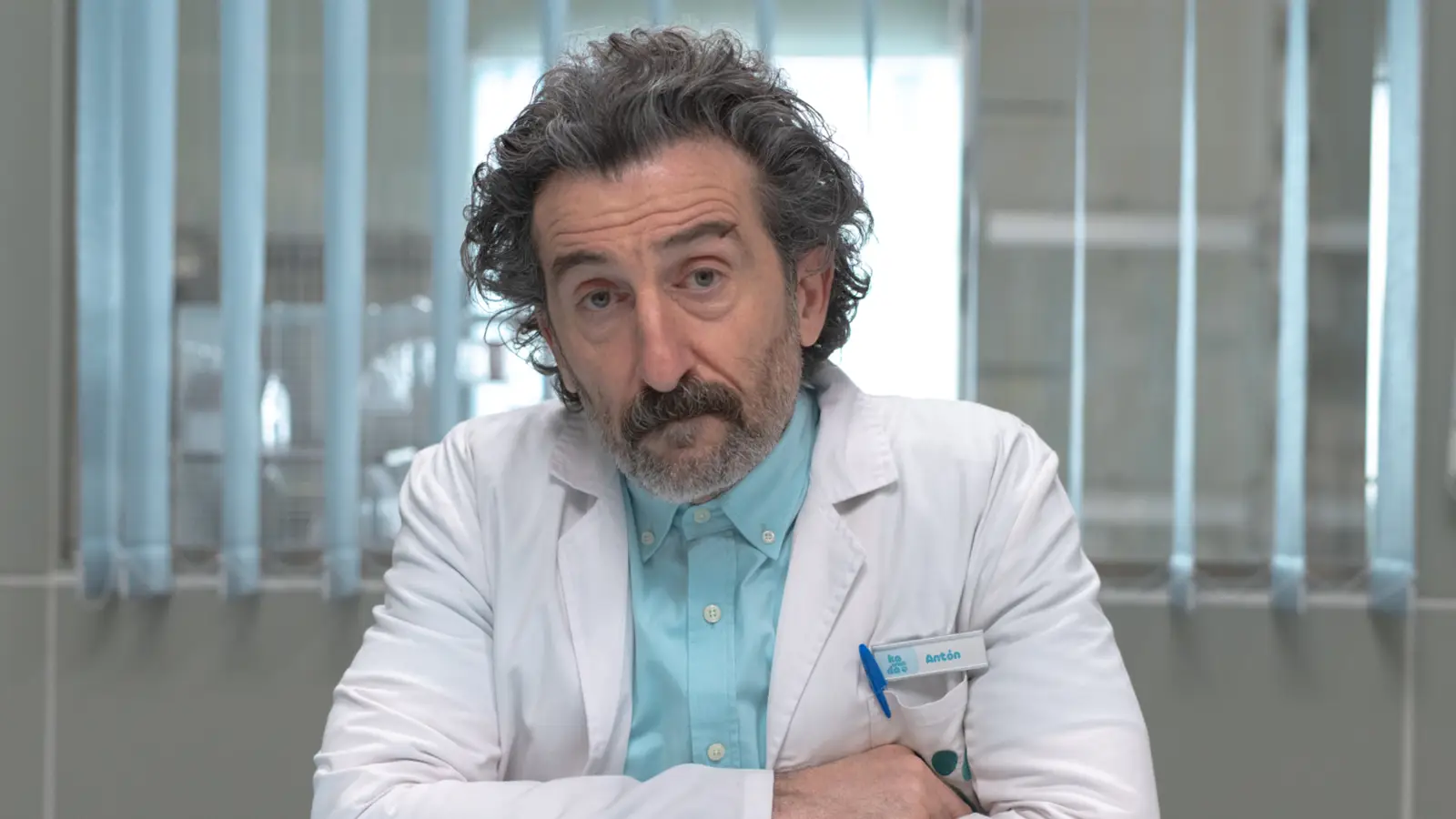

One morning earlier this year, as Deb Capistrano came on duty for her shift as a nurse in her hospital’s stroke unit, her colleagues from the night shift warned her that one of her patients for the day was a man who’d been threatening to harm them.

Capistrano has been a registered nurse for 17 years. Threats of violence aren’t new to her. Across the nation, hospitals have become some of the most violent workplaces in America, where health care workers experience workplace violence at triple the rate of all other private industries combined, federal statistics show.

For Capistrano, the worry that she could be hurt while doing her job is always in the back of her mind.

But in California, where she works, robust state law requires hospitals to create detailed violence prevention plans specific to the needs of each hospital unit, with input from frontline workers like nurses.

When Capistrano arrived on duty, nursing management already had a plan to keep her safe. For example, every time Capistrano entered the patient’s room she had an escort, and hospital security did their rounds more frequently on her unit.

“In that moment, I felt really safe,” she told Stateline. “There were a lot of different things in place that day to prevent any harm. I think that’s largely due to having that law in place.”

Health care workers such as Capistrano make up just 10% of the American workforce but experience 48% of the nonfatal injuries from workplace violence, according to federal data.

And the threat is increasing. The number of health care providers who reported harassment at work from patients, patients’ families and colleagues more than doubled between 2018 and 2022, according to the latest data available from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Research has found workplace violence in health care is increasingly common due to a number of factors. Some are organizational: not enough staffing, long patient wait times or lack of appropriate security. Patients’ expectations about how fast or easy it should be to access care appear to have increased in recent years, as the costs of health care have gone up.

Researchers have also found that public attitudes are being shaped by politicians who might promote or undermine health services for political gain, particularly relating to contentious topics such as vaccination, masking or abortion.

With threats against nurses, physicians and other staff on the rise, state lawmakers and hospital officials are scrambling to put stronger protections in place. Those include increased criminal penalties, armed security guards and violence prevention plans.

This year, Ohio, Oregon and Washington enacted laws designed to curb workplace violence in health care spaces by requiring employers to create and carry out detailed violence prevention plans. Such plans can include risk assessments specific to each hospital unit, staff training on de-escalation techniques, increased security and a clear policy for reporting incidents.

Dozens of states — including California, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine and Texas — have enacted laws aimed at curbing violence in hospitals and clinics, the vast majority of them in the past decade. Legislators in other states, including Alaska, Massachusetts, New York and Wyoming, introduced similar legislation in their most recent sessions.

Prevention and punishment

A few years ago, during a shift in the emergency department at a hospital in Maine, nurse Meg Sinclair was tending to an older patient who became increasingly agitated. The patient grabbed both sides of her stethoscope and tried to strangle her.

Sinclair, who now works at Maine Medical Center in Portland, has been a nurse for 11 years. She’s spent most of that time in hospital emergency departments, where the potential for chaos never feels far away. A fellow nurse recently told her about getting her nose broken by a patient.

“It’s kind of crazy because nurses unfortunately normalize these horrific things that happen to them,” Sinclair told Stateline.

“You’re feeling scared in an environment where you shouldn’t have to, in your workplace where you’re trying to help people.”

In Maine, a 2023 law toughened the punishment for assaults that occur in a hospital emergency department.

To Sinclair, the law felt performative. She believes adding harsher penalties doesn’t do much to prevent assault from happening in the first place.

“It’s just not effective because it’s reactionary,” she said. “It’s frustrating, because the last thing I’d want to do is blame the patients. They’re often sick and scared, and not in their right mind.”

But proponents of such laws have said they’re needed to help law enforcement hold offenders accountable. Other states, such as Georgia, also have increased criminal penalties for assaults on nurses and other health care workers.

Maine Democratic state Rep. Holly Stover introduced a bill this year to extend her state’s harsher penalties to assaults on all health care workers, not just those working in the ER. She told Stateline that the penalties would only apply to people deemed competent to face such charges, not those unable to understand the consequences of their actions.

Her bill passed the House but was indefinitely postponed in the Senate in June. While Stover will leave office next year due to term limits, she hopes another lawmaker will reintroduce the bill.

“I’ve seen workers who have had broken cheekbones, broken noses, broken jaws,” said Stover, who has worked in health care and social services, and serves as a trustee for her local hospital.

“Any legislation that can better address the prevalence and potential for violence in health care settings is going to be critically important.”

Other states have focused on stepping up hospital security. A 2023 North Carolina law, for example, requires hospitals with emergency departments to have a law enforcement officer — not just unarmed security guards — on campus at all times.

But many hospitals have already gone down that road.

Hospital police forces

In September, WellSpan Health, a nine-hospital system in southern Pennsylvania, announced it would create its own private police force, adding armed officers to supplement its unarmed security team. The system will also be increasing its weapons detection equipment at hospital entrances.

WellSpan is in the same region of Pennsylvania where, in February, a gunman entered the intensive care unit at UPMC Memorial Hospital and took staff members hostage before he was killed by police. The shootout left one officer dead, and it wounded a doctor, a nurse, a hospital custodian and two other officers.

A growing number of hospitals are launching their own police forces, said Tony Pope, the chief of police and emergency preparedness at Columbus Regional Health in Columbus, Indiana, south of Indianapolis.

At least 29 states allow hospitals to create their own police forces, with officers who can carry firearms and make arrests, according to the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety, a professional association for safety and security directors at health care facilities. Pope, who is president-elect of the association, said the levels of authority and jurisdiction for such officers can vary from state to state, but they’re able to carry firearms and make arrests.

At Indiana’s state police academy, health care is the fastest-growing contingent of police officers in the state, Pope said.

High-profile incidents nationwide have prompted more health systems to beef up their security. In 2023, a man opened fire in the waiting room of an Atlanta medical practice, leaving one woman dead and four others wounded. A few months later, a visitor at an Oregon hospital opened fire and killed a security guard, and a doctor was shot and injured at a Dallas-area medical center. The year before, a man killed his surgeon, another doctor, a receptionist and a visitor at a Tulsa, Oklahoma, medical office.

Workplace violence cost hospitals an estimated $18 billion in 2023 alone, according to a recent report from the American Hospital Association.

Pope said his force in Columbus has seen a 56% reduction in violent incidents since 2023.

And police forces aren’t just for the big systems anymore. Smaller hospitals, too, are testing the waters. In July, the 25-bed Perry County Memorial Hospital in southern Indiana announced it would begin hiring officers for its new police force this fall.

Scrubs and security

Sinclair often talks with other nurses about their workplace needs as a member of her local nurses union. She believes the best action state legislators could take to combat violence in health care is to require hospitals and other clinics to maintain certain nurse-to-patient ratios and penalize employers that exceed them.

“When we’re short-staffed and someone’s begging for help and you can’t get to them because you’re running between eight different rooms putting out fire after fire, then you get the verbal assault, the hair pulling,” said Sinclair, who said she’s experienced all of those things.

“You have to meet people’s needs or else they resort to things they otherwise wouldn’t do.”

Nursing groups have for years requested nurse-to-patient ratios. Only a handful of states, including California, have passed such laws.

Hospital systems and other employers argue ratios don’t give them needed flexibility in hiring, and could threaten the financial safety of some institutions that might be forced to close units if they can’t meet the ratios.

Pope said that in his experience, hospitals and other health employers likely need several different laws and policies in place, from prevention plans to added security measures.

“When it comes to addressing workplace violence, it really is important for health care facilities and systems to have that multipronged approach,” he said.

Stateline reporter Anna Claire Vollers can be reached at avollers@stateline.org.