By Yoav Zitun

Copyright ynetnews

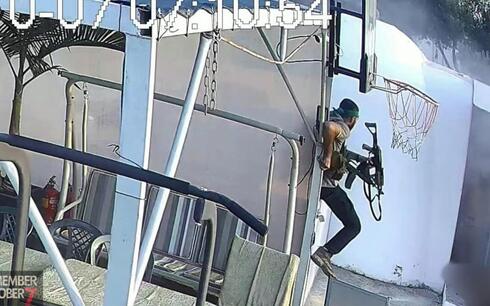

On the morning of Oct. 7, 2023, then-commander of the Duvdevan Unit, Col. D, saw the fin of an RPG rocket whistle past his face and slash the neck of an officer who had jumped with him into the inferno at Kibbutz Kfar Aza. Together with the other soldiers, they gave him lifesaving treatment and continued the battle, which only ended after three days. Col. D had one advantage that day: he had raced from the unit’s base near Jerusalem in an armored jeep, heavily armed with grenades and explosives. He did so on his own initiative, and luckily still remembered the kibbutz from his time as commander of the sector as the 202nd Paratroopers Battalion commander three years earlier. Alongside him was an operative who lived in Kfar Aza and was of great help. That moment was also the starting point for an unofficial unit inquiry that Col. D began as soon as the dust started to settle, even before preparations for the large ground maneuver that followed three weeks after the massacre. Again, without anyone assigning him the task, he went from soldier to soldier with a small notebook, asking, questioning, checking, and collecting. He knew that soon the IDF would embark on a long and exhausting campaign to capture the Gaza Strip. He wanted to strike while the iron was hot. “Things can get confused in people’s minds, be forgotten,” he told me in the field less than a week after the massacre. “We have to collect information now to learn what happened to us and to provide a solid basis for investigations. As commanders, we can’t wait for others to investigate us.” His fellow paratroopers went even further, sending reserve officers from their units to hospitals to interview wounded troops on camera, fearing their condition might deteriorate or their memories fade under medication. About a month later, in the last days of November 2023, the IDF high command faced a decision. Chief of Staff Herzi Halevi used the cease-fire during the first hostage deal with Hamas to convene a closed consultation with top generals. On the table lay the hot potato everyone wanted to avoid: whether to launch inquiries into the massacre while the war was still ongoing. Resistance in the room was immediate. “We’ll end up in mud fights and finger-pointing inside the army, which will do more harm than good,” one general warned. Halevi proposed starting from the top down: first the General Staff and himself, then the strategic “conception” that guided IDF leadership, and intelligence on Hamas, and only afterward examining the tactical level—the failures of the Gaza Division and Southern Command, and the battles in the border communities. Halevi preferred an external panel of retired generals, free of internal pressures, like those that investigated the failures of the 2006 Lebanon War. Selected for the mission were retired Maj. Gen. and former Rafael CEO Yoav Har-Even retired Maj. Gen. Sami Turgeman and former Chief of Staff Shaul Mofaz, who was slated to examine Halevi himself. But before a formal mandate was prepared, events took a turn. In early January 2024, Ynet reported the decision. Minutes later, political fury erupted. Cabinet ministers, perhaps fearing blame creeping toward them, demanded cancellation of the external panel. Halevi had failed to update Defense Minister Yoav Gallant in time, and Gallant did not back him against the political pressure. Halevi relented, settling instead for internal investigation teams led by active-duty and reserve colonels and brigadier generals. In a few cases, inquiries were supervised by retired generals. Thus, reserve brigade commanders and senior staff officers found themselves, in the middle of war, investigating the failures that led to its outbreak. “I’d come out of a month of fighting in Gaza, stop by the forward brigade command post, and then go interview another civilian at a kidnapping site in one of the communities,” recalled one colonel of his routine in 2024. “When I was at Tze’elim preparing my battalions for the next maneuver, I’d also encounter regular units and see the same cultural problems we identified in the investigations—from lack of basic discipline to faulty command doctrines and poor management of combat units. It was frustrating. The army must return to its core military fundamentals. But that won’t happen overnight.” The start of the IDF inquiry In March 2024, as the IDF was at the peak of its Khan Younis maneuver and reducing forces in the north of Gaza, the General Staff issued a formal investigation order: 48 battle inquiries, plus four strategic investigations: 1) intelligence, 2) decisions made on the night of Oct. 6–7, 3) Southern Command’s performance in the defensive battles, 4) security policy toward Gaza in the years leading up to the war. A special section was devoted to the Air Force, detailing every plane and helicopter during the crucial hours, where it struck, when, and whether it influenced the ground battle. In addition, about 100 other investigations were conducted on secondary issues such as logistics, weaponry, and local defense. According to the IDF, 400 officers participated, drawing information from some 1,200 sources. Over time, the Doctrine and Training Department in the Operations Directorate developed a standardized format for the inquiries. They built models with graphs mapping the balance of forces minute by minute in every battle zone. The investigators worked like detectives: mapping scenes, cross-checking surveillance footage, Hamas GoPro videos, Facebook Live broadcasts of atrocities, IDF and Hamas radio communications, civilians’ WhatsApp messages, and testimonies from everyone involved—from captured Hamas terrorists to released hostages. The complex process also included field reenactments with platoon and company commanders, often under difficult circumstances. In at least one case, eight months after the war began, Golani officers were pulled from their post on the Lebanese border to explain what happened in their sector on Oct. 7. A special team collected intelligence materials from Gaza, including Hamas’ operational plan for capturing the Nahal Oz base, with intimate details of the routine inside the outpost adjacent to the Shuja’iyya neighborhood. “Where there was disagreement—between a soldier and a commander, between a civilian and a terrorist, between raw intelligence and visual evidence—we convened expert panels to reconcile contradictions,” explained one investigator. “In a long and complex battle, everyone’s perspective is different. Our mission was to average the evidence to reach conclusions. Sometimes disputes were about an infiltration route, other times about friendly-fire casualties or kidnapping sites. In such cases, we also used forensic investigations.” An officer involved in the process added, “There were plenty of delays. For example, during the Lebanon maneuver, some investigators were themselves fighting Hezbollah and were unavailable. Or when we realized a civilian was likely killed by our own forces, we pursued the case for two months, right up to the chief of staff. We didn’t spare criticism, even when it was painful: cases of soldiers and commanders abandoning combat zones, or a tank withdrawing from a kibbutz guard post with terrorists still present. We didn’t want to hide anything. Already we’ve reinforced units, made corrections, improved systems, and set up new formations.” The problem of personal accountability A senior officer from Southern Command, at the heart of the failures on Oct. 7, was assigned legal counsel paid by the army just months into the war. Military attorneys, the elite of the legal corps, came to his office in the Gaza Division headquarters at Re’im camp, as gunfire and explosions echoed outside. The bullet holes from that Saturday’s battle, when Hamas’ elite Nukhba terrorists overran the base, were still visible on the walls. The lawyers coached him on what to say—and what not to say—to IDF investigators, warning that his testimony might later reach a state commission of inquiry, or even lead to a criminal probe by military police for gross negligence. Minutes after the meeting, he climbed into his command jeep and drove into Gaza to oversee another critical mission. This illustrated a central problem: the IDF chose to investigate Oct. 7, to lance wound after wound, but without punishing or dismissing those who had watched metaphorical and physical breaches in the border fence widen into catastrophic failures. Such shortcomings contributed heavily to the tragic outcomes. One inquiry into the battle at Nahal Oz base found blatant disregard of operational procedures, lack of brigade oversight, and inadequate defenses. The colonel leading the team exceeded his limited mandate and bluntly recommended dismissals. But this was rare. From the start, inquiries were conducted under orders not to recommend personal accountability. As a result, from Chief of Staff Halevi, who resigned only in early 2025, through Gaza Division commanders, Southern Command, and senior branches in intelligence and operations, officers linked to the failures remained in place. This decision fostered unity within the ranks during the war. If the top leadership stayed in position, lower levels could as well. “We had our eyes on the officers at the heart of the Oct. 7 failure who kept fighting the war,” said a senior military source. “We also feared dismissals before inquiries were completed would lead to court challenges and damage the army. For a year and a half, we managed to function together, without generals fighting each other.” In one of his final acts, Halevi handed his successor, Chief of Staff Eyal Zamir, a file with personal conclusions about officers still serving—recommendations now under review by the panel led by retired Maj. Gen. Sami Turgeman. Soon, those personal conclusions are expected to be made public, targeting the last officers who have yet to accept responsibility. The political dimension Senior officers from Southern Command and Military Intelligence were promised that no personal conclusions would be drawn to encourage candor. Still, many came away frustrated with the process. That was evident as early as July 2024, when the IDF published its first public report on the battle at Kibbutz Be’eri, where about 130 people were killed or kidnapped. The report directed most criticism at the forces that fought there, including the elite Shaldag unit, prompting backlash and forcing Halevi to meet the furious fighters personally. One lesson was to change the order of publication: first present core strategic inquiries, covering the General Staff and the interface between the IDF and the political echelon. But even then, political tremors followed. The strategic “conception” that allowed the massacre had a central political partner—Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who led Israel for most of the decade and a half in which Hamas grew into a heavily armed force of 30,000 terrorists with special units. Political anger at the probes was not only verbal. For example, the state comptroller questioned why the Nova music festival massacre was investigated without cooperation from the Shin Bet and police. “We sent a senior investigator to an initial meeting with police, but hours later we discovered the conversation had been recorded and leaked,” a senior officer recalled. “If we had worked with Shin Bet, which refused anyway, we’d have been accused of coordinating stories. Every path risked turning the investigations into blame games against the IDF alone.” Critics also noted that some officers investigated battles they themselves fought in. “There was a reserve brigade commander who fought in a kibbutz and investigated the battle,” one officer explained. “But that gave him perspective and firsthand understanding of the command and control failures in those first 48 hours. At the start, we had a few volunteers for this sensitive task. Of course, we’d have preferred investigators not in the middle of fighting.” With the police, relations were smoother. The IDF consistently highlighted the heroism of police commanders in the Negev, whose quick decisions saved thousands of lives. “A few months ago, a team led by former deputy commissioner David Bitan came to learn from us,” an IDF official said. “At the end, he told us he had seen brave, professional, and vital investigations—that history will judge us.” What comes next The saga of the IDF’s Oct. 7 inquiries is not over. The Turgeman Committee is expected soon to present its conclusions, including additions, revisions, and personal recommendations to Zamir. “Many battalion and brigade commanders were angry that the inquiries created a narrative pinning failures on them, not senior levels,” said an IDF source. “But all these commanders took responsibility, even those who rushed to the border from other commands.” Turgeman’s panel may also confront the most sensitive issue: the core strategic inquiries, which some insiders say did not go far enough. “There was a major effort to ignore the political echelon as the long-term policy-setter,” said a senior officer. “Much of what the army knows about the conception wasn’t presented.” Those who tried to point fingers upward paid a price. Former Shin Bet chief Ronen Bar published a brief version of the agency’s Oct. 7 probe, which, though thin, included facts showing the government had enabled Hamas’ funding and buildup for years. Meanwhile, the Southern Command chief on Oct. 7, Maj. Gen. Yaron Finkelman, who resigned in early 2025, has spent his extended release period poring over reports, filling gaps, and refining findings. Both he and Halevi have personally presented investigations in affected communities, staying late into the night, answering painful questions, and sometimes sitting silently through survivors’ cries. But the IDF has not released written versions of the inquiries to communities or the public, beyond a few battle charts. “Even within communities, sensitivities exist—residents blaming local security coordinators, or disputing specific details,” a senior officer said. “It’s a hard job. But if we don’t continue to face civilians, in person, we’ll never rebuild the trust that collapsed on Oct. 7.” Once public presentations end and dismissals tied to Turgeman’s recommendations are implemented, the IDF will open another Pandora’s box: investigations of the ground offensive launched on Oct. 27, 2023. That will tackle a question as existential as Oct. 7 itself—why the IDF has not been able to defeat Hamas.