By Stabroek News

Copyright stabroeknews

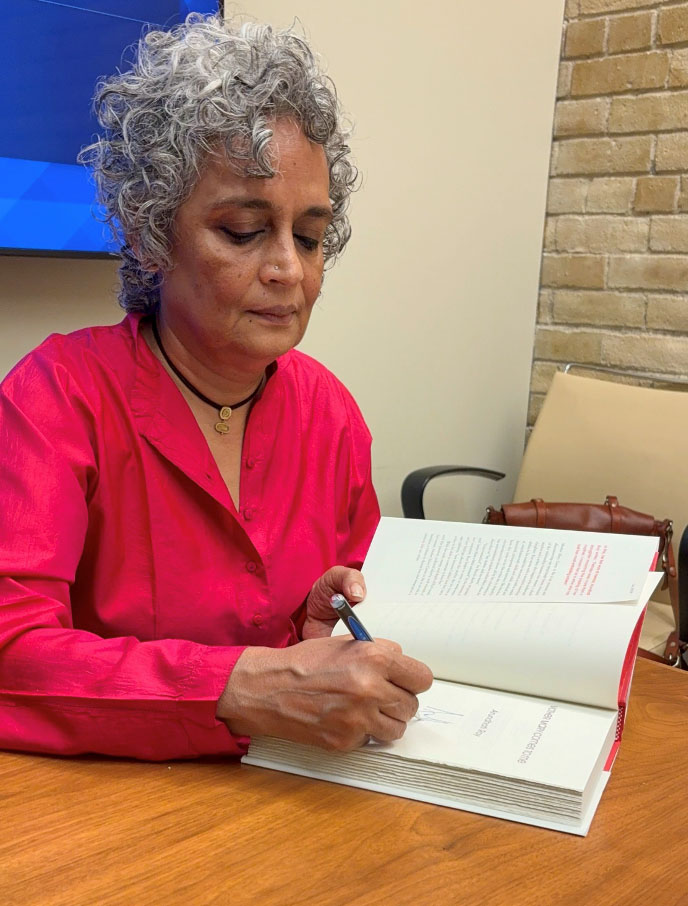

Last Friday, Delhi based writer Arundhati Roy electrified a capacity crowd at Convoca-tion Hall, the largest auditorium at the University of Toronto. It was one of only two stops in Canada to promote the publication of Mother Mary Comes to Me (Simon and Schuster Canada), a remarkable memoir that captures, with vulnerability and honesty, the complexity and fierce integrity of a daughter’s love for her mother.

Arundhati Roy is the author of the Booker Prize winning novel The God of Small Things (1997), and The Ministry of Utmost Happi-ness, longlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2017. Her works of nonfiction include The End of Imagination; Capitalism: A Ghost Story; The Doctor and the Saint; My Seditious Heart; and Azadi.

Publishing House Simon and Schuster Canada provides readers with the following introduction to the book:

“Mother Mary Comes to Me, Arundhati Roy’s first work of memoir, is a soaring account, both intimate and inspirational, of how the author became the person and the writer she is, shaped by circumstance, but above all by her complex relationship to the extraordinary, singular mother she describes as “my shelter and my storm.”

“Heart-smashed” by her mother Mary’s death in September 2022 yet puzzled and “more than a little ashamed” by the intensity of her response, Roy began to write, to make sense of her feelings about the mother she ran from at age eighteen, “not because I didn’t love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her.” And so begins this astonishing, sometimes disturbing, and surprisingly funny memoir of the author’s journey from her childhood in Kerala, India, where her single mother founded a school, to the writing of her prizewinning novels and essays, through today.

With the scale, sweep, and depth of her novels, The God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, and the passion, political clarity, and warmth of her essays, Mother Mary Comes to Me is an ode to freedom, a tribute to thorny love and savage grace—a memoir like no other.”

Opening the evening in Toronto with an expression of solidarity with Palestine, Arundhati Roy offered a twenty-minute reading from Mother Mary, before sitting down with Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, writer and artist Leanne Betasamosake, for a moving conversation that captured, with humour and grace, a writer’s craft in navigating the political in the personal. After a second reading from her memoir, Roy closed the evening (to a standing ovation) with a section from ‘The End of Imagination.’ It was the first political essay she published after The God of Small Things, written in response to nuclear tests carried out by the Indian government in 1998. We reprise the excerpt Arundhati Roy shared with and for us last Friday. In this moment, in a world on fire, these timely words keep our feet to the fire, with the quiet certainty that as Roy has elsewhere said, “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.’”

ARUNDHATI ROY: I told my friend there was no such thing as a perfect story. I said in any case hers was an external view of things, this assumption that the trajectory of a person’s happiness, or let’s say fulfillment, had peaked (and now must trough) because she had accidentally stumbled upon ‘success.’ It was premised on the unimaginative belief that wealth and fame were the mandatory stuff of everybody’s dreams.

“You’ve lived too long in New York” I told her. “There are other worlds. Other kinds of dreams. Dreams in which failure is feasible. Honorable. And sometimes even worth striving for. Worlds in which recognition is not the only barometer of brilliance or human worth. There are plenty of warriors that I know and love, people far more valuable than myself, who go to war each day, knowing in advance that they will fail. True, they are less ‘successful’ in the most vulgar sense of the word, but by no means less fulfilled.” “The only dream worth having,” I told her, “is to dream that you will live while you’re alive and die only when you’re dead.”

(Prescience? Perhaps.)

“Which means exactly what?” (Arched eyebrows, a little annoyed).

I tried to explain, but didn’t do a very good job of it.

Sometimes I need to write to think. So I wrote it down for her on a paper napkin. And this is what I wrote: To love. To be loved. To never forget your own insignificance. To never get used to the unspeakable violence and the vulgar disparity of life around you. To seek joy in the saddest places. To pursue beauty to its lair. To never simplify what is complicated or complicate what is simple. To respect strength, never power. Above all, to watch. To try and understand. To never look away. And never, never to forget.”