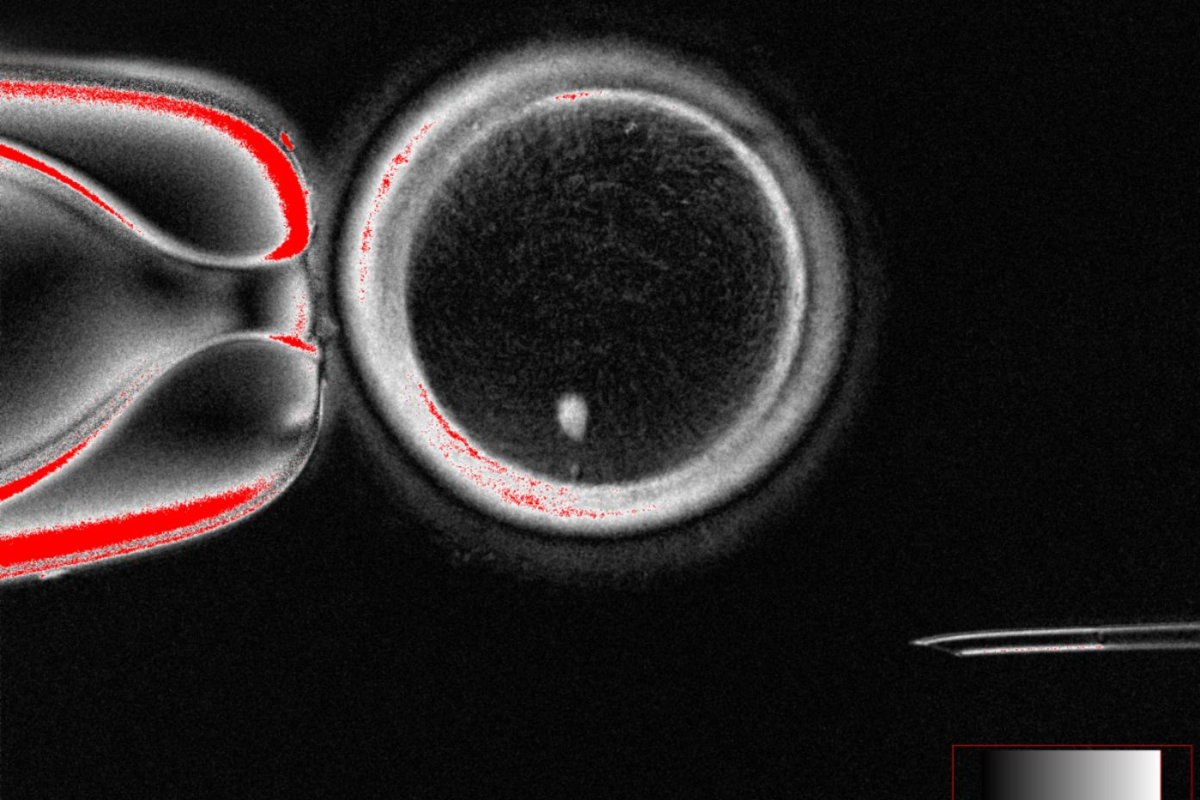

For the first time, scientists have created fertilizable human eggs from skin cells—an advance that the researchers say could pave the way for new infertility treatments, though the technology remains in its infancy.

In their study, the team led by biologist Shoukhrat Mitalipov of Oregon Health & Science University reprogrammed adult human skin cells into egg cells that were then successfully fertilized in the lab.

The breakthrough hinges on a novel process the team calls “mitomeiosis,” which forces a skin cell’s full set of 46 chromosomes to divide in a way that mimics how natural eggs reduce their genetic content by half.

This step is critical, since fertilization requires an egg with 23 chromosomes to combine with sperm carrying another 23.

The researchers produced 82 functional oocytes (eggs) using the method, fertilized them with sperm, and found that around nine percent developed into blastocysts—the earliest stage of embryo development—by day six. No embryos were cultured beyond this point.

While groundbreaking, the study is far from a clinical application. The majority of embryos did not develop normally, the researchers reported—and those that did frequently showed chromosomal abnormalities.

The researchers emphasize that years of additional research are needed to establish whether the approach could ever be safe and effective in people.

Still, experts say the findings are significant. “This insightful piece of research demonstrates that the chromosomes of a differentiated adult cell… can be persuaded to undergo a specific kind of nuclear division that would normally seen only in eggs or in sperm,” said Roger Sturmey, a professor of reproductive medicine at the University of Hull, who was not involved in the present study.

“It opens up the possibility of creating functional new egg cells, containing genetic material that can—in principle—be taken from cells from anywhere in the body,” he added.

However, Sturmey noted that the technique currently has low success rates and stressed the importance of “robust governance” and public dialogue as the science advances.

“For the first time, scientists have shown that DNA from ordinary body cells can be placed into an egg, activated, and made to halve its chromosomes,” said Ying Cheong, professor of reproductive medicine at the University of Southampton, who was also not involved in the present study.

She called the work an “exciting proof of concept” that could one day transform how infertility and miscarriage are understood and treated.

Professor Richard Anderson of the University of Edinburgh agreed, saying the ability to generate new eggs would be a “major advance.”

Infertility affects millions worldwide. For some individuals—such as women who lose their eggs after cancer treatment or those born without functioning ovaries—current treatments like in vitro fertilization (IVF) offer no path to genetically related children.

“There will be very important safety concerns but this study is a step towards helping many women have their own genetic children,” Anderson explained.

The authors acknowledge major challenges remain. Most of the lab-created embryos failed to progress, and chromosome segregation during mitomeiosis was random, raising the risk of genetic errors.

Nonetheless, the study marks an important step in demonstrating that reprogramming adult human cells into fertilizable gametes is technically possible.

If future refinements improve safety and efficiency, the approach could usher in a new era of reproductive medicine—though experts stress that is still many years away.

Do you have a question about reproductive health? Let us know via health@newsweek.com.

Reference