By Jaclynn Ashly

Copyright therealnews

Republish this articleThis work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

We encourage republication of our original content. Please copy the HTML code in the textbox below, preserving the attribution and link to the article’s original location, and only make minor cosmetic edits to the content on your site.Branded as Terrorists: Kenya’s use of anti-terror laws against Gen Z protesters

by Jaclynn Ashly, The Real News Network September 29, 2025

Branded as Terrorists: Kenya’s use of anti-terror laws against Gen Z protesters

by Jaclynn Ashly, The Real News Network September 29, 2025

Veronicah Mbindyo is among the scores of young Kenyans caught up in mass arrests after June 25 anniversary protests, which marked a year since the country’s historic Gen Z uprising, when tens of thousands of youths united against crippling living costs and government corruption.

Later, police informed her of her charge: terrorism.

“I was shocked,” says the 21-year-old, sitting in her small room in Matuu, a town in eastern Kenya. “I was so confused. To me, a terrorist is a really bad person—someone covering their face, throwing grenades, shooting people.”

“But… hey, I guess I’m Al Shabaab now,” she says mockingly, releasing an edgy laugh.

Mbindyo is one of hundreds of youths across the country facing serious charges since June 25 ranging from arson to terrorism, which carry steep bail and harsh sentences. At least 75 have been charged with terrorism.

Kenya has now joined a disturbing global trend. Similar tactics have been used in the U.S., U.K., and Germany to suppress grassroots movements, including pro-Palestinian and climate activism.

Turning the country’s anti-terror laws on an entire generation of protesters marks an unprecedented escalation of state repression, Kenyan experts warn.

Kenya has now joined a disturbing global trend. Similar tactics have been used in the U.S., U.K., and Germany to suppress grassroots movements, including pro-Palestinian and climate activism. Under President William Ruto, Kenya has adopted the same playbook, using terror charges to impose crushing financial burdens and social stigma—making clear to the country’s youths that protests will bring life-altering consequences.

“I’m still traumatized by this,” Mbindyo tells The Real News Network, her eyes fixed on the floor. “Even now, I don’t feel like myself; I’m constantly stressed.”

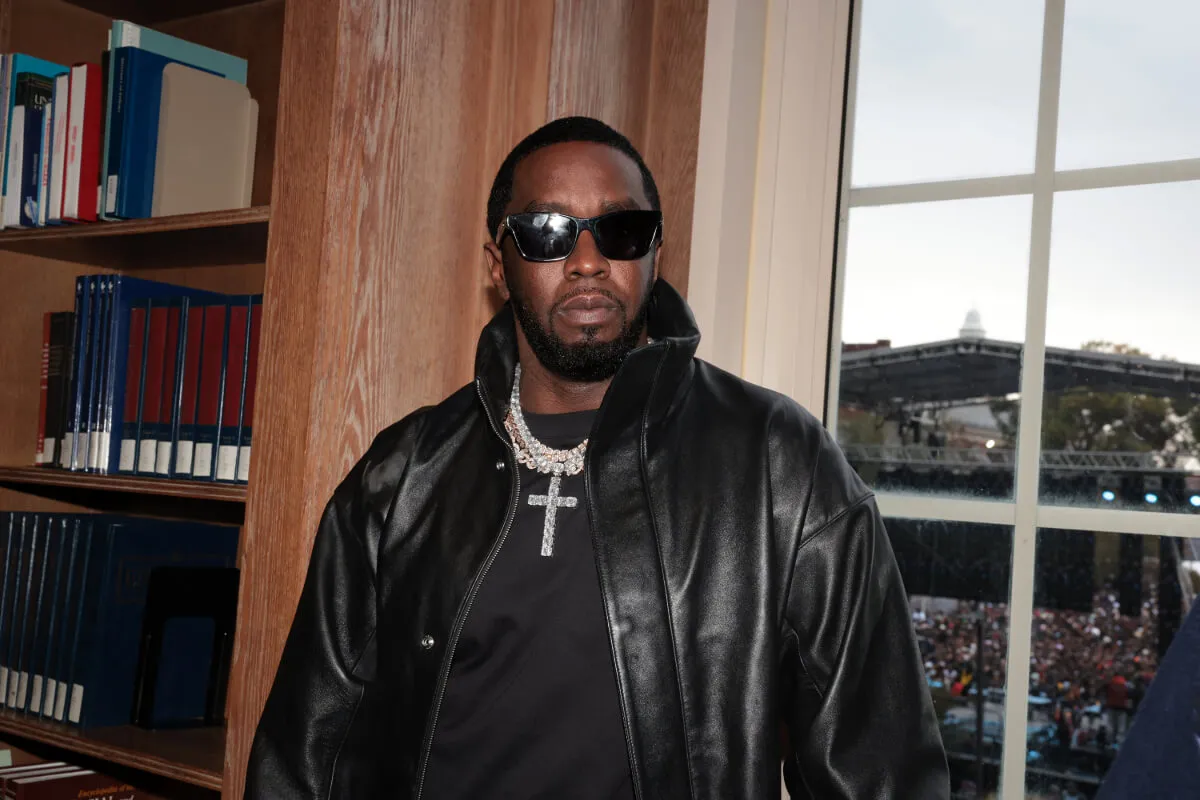

Veronicah Mbindyo, 21, was shocked to be charged with terrorism. Her case is part of a broader trend of weaponizing anti-terror laws against peaceful protesters. Photo by Jaclynn Ashly.

‘Bad dream’

Mbindyo didn’t attend the June 25 protests. Working at a fuel shop in the town center, she closed early and went home when the demonstrations began. She was shocked, then, when police arrived at her workplace days later and took her into custody.

“The police just questioned me about what I saw during the protests,” Mbindyo recounts. “I told them I didn’t see anything because I wasn’t there.” The next day, she was charged with arson, accused of attacking officers and smashing police station windows.

“The whole time I had no idea what they were talking about,” she says. Her bail was set at 200,000 Kenyan shillings ($1,548 USD).

After several days, her mother, an informal vegetable vendor, managed to get her out on a surety bond. But weeks later, Mbindyo was rearrested with seven other youths and taken to Nairobi’s Kahawa Law Courts, which handle terrorism cases. She was informed of her charge and given a 200,000-shilling cash bail.

She was then transferred to Langata Women’s Prison for two weeks. “Those days were one big nightmare,” she says, shaking her head. “The first day I couldn’t cope. I had a crushing headache and so much stress. I thought I’d be stuck in prison forever because I didn’t know how my family could get that kind of money.”

“I kept thinking, why me? I was the only girl arrested in Matuu, and I wasn’t even at the protests. Why did the police have to come for me?” Eventually, the court lowered her bail to 50,000 shillings ($387), and her mother took out a loan to free her.

Franklin Wambua, 25, was also rounded up, despite also not attending the June 25 protests. “I didn’t know what was going on,” he recalls. “I couldn’t even remember the last time I did something bad.”

Franklin Wambua in his hometown of Matuu, where terrorism charges have left young protesters and their families carrying heavy social and financial burdens. Photo by Jaclynn Ashly.

Accused of throwing stones at police, he was charged with arson and given 200,000-shilling bail. Transferred to Yatta Prison, he was denied contact with his mother for nearly a month. “It was my first time ever being arrested,” says Wambua, who has a three-month old child. “There were so many people in one small cell, and the food was disgusting. I was going crazy thinking about my mother because she had no idea if I was alive or dead.”

By the time he appeared in court weeks later and finally spoke to his mother, he was at his breaking point. “I just told her I will confess to whatever they want so they can take me to jail,” he recalls. “I was skinny. I felt so tired and weak. I just wanted everything to be over.”

But his ordeal was just beginning. Police soon bundled him and several other young men into a white van. “I honestly thought we would be slaughtered—that this is how they would make us disappear.”

He was also taken to Kahawa Law Courts and charged with terrorism, an offense carrying up to 30 years in prison. “I couldn’t believe it,” Wambua says with a deep sigh. “I’ve never stolen or hurt anyone. How is this real? I thought my life was over — that I’d rot and die in prison.”

From there, he was transferred to Kamiti, Nairobi’s maximum-security prison for the country’s most violent offenders. “Kamiti is a place I used to see on TV,” he says. “That’s where murderers go, not people accused of petty things. I just prayed constantly, asking God to open up a way for me to get released.”

Inside, he was in a large hall with about 70 other young Kenyans, all charged with terrorism. “They were all really scared,” he tells TRNN. “Some were just quiet, lost in their thoughts.” Even some guards seemed astonished, reassuring the youths the charges wouldn’t hold.

After three weeks, Kenyan activists crowdfunded his 50,000-shilling bail, securing his release.

Yet the weight of these charges has extended far beyond prison, closing doors to opportunities and jobs and casting a dark shadow over these youths’ lives.

“I feel like I’m stuck in a bad dream and I just want to wake up,” Wambua says, dragging his hands down his face.

Framing the youths

Since the June 25 and annual pro-democracy “Saba Saba” protests in July—which left dozens of protesters dead—authorities arrested about 1,500 people. Hundreds, mostly under 25 years old, face terrorism and other serious charges, including murder, arson, sexual assault, and robbery with violence.

Seventy-five are being prosecuted under the 2012 Prevention of Terrorism Act, designed to combat insurgent groups like Al Shabaab, the Somalia-based Al Qaeda affiliate that has carried out numerous deadly attacks in Kenya. In Matuu alone, 23 youths have been charged with terrorism.

Yet many of these arrests remain unaccounted for. “Out of the 1,500 youths the Interior Ministry claims to have arrested, we’ve only traced 500,” says Andrew Mugo, a lawyer who is heading the legal team representing the youths. “The other 1,000 we know nothing about—they either haven’t been taken to court or were taken to courts we don’t know about.”

Kenya’s civic space has narrowed sharply under Ruto, and targeting youths with terrorism charges is the latest escalation, says Otsieno Namwaya, associate director of Africa research at Human Rights Watch.

“Even peaceful protest is now treated as a threat to the state.”

“Even peaceful protest is now treated as a threat to the state,” Namwaya tells TRNN from hiding, citing state threats. “Officials portray demonstrations as attempted coups to justify extreme punishments—including shootings, abductions, and disappearances—while pushing a counter-narrative that protests are driven by looting and violence.”

Experts contend that framing protests as terrorism signals an unparalleled heightening of state repression in the country.

Previously, demonstrators were often charged with unlawful assembly, which mostly meant endless court dates. Terrorism charges, however, give police sweeping powers: suspects can be detained for up to 90 days without trial, their property and bank accounts scrutinized, and bail set prohibitively high, explains Namwaya.

Past Kenyan governments misused counterterrorism laws to try and silence critics, but targeting an entire movement is new. “It has never been to this extent where it has been weaponized against peaceful youths whose only weapons are cameras, water bottles, and Kenyan flags,” says Mwaura Kabata, vice president of the Law Society of Kenya (LSK). “Only this government has taken laws created to protect people and specifically used them against its own.”

The crackdown has also extended online, with authorities disrupting internet access, tightening rules for social media, advancing real-time surveillance legislation, arresting activists under the Cybercrimes Act, and pushing new bills to curb both online and offline dissent.

Beyond the courts, rights groups accuse the state of using informal vigilantes, or “state-hired goons,” sometimes alongside uniformed police, to destroy property, assault, loot, and intimidate. These groups—often criminal gangs and militias hired by senior politicians—have been deployed to discredit peaceful protests and create a pretext for the state’s violent crackdown.

During the June 25 anniversary protests, these vigilantes, armed with clubs and whips and backed by police, attacked demonstrators, while authorities banned live coverage and switched off leading television stations.

“We know that those who destroyed property or looted during protests were state-hired operatives,” Mugo tells TRNN. “Yet you will not find one of them being escorted by a police officer into court.”

Instead, authorities have tried to shift blame onto Kenya’s youths for the unrest.

According to Mugo, the evidence against the youths is “absolute rubbish,” with police as the state’s sole witnesses. The supposed proof—mostly photos of police station damage—fails to connect any youth to the alleged crimes.

“I am very confident these cases will be thrown out,” Mugo says. “They will never meet the bar of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that any of the accused did what they’re charged with.”

But the drawn-out process still brands youths as security threats, barring them from jobs requiring clearance or furthering their studies. Even with volunteer lawyers and activists fundraising for bail, the fallout lingers: it may take a year just to have charges dropped, followed by another process to clear their records.

“These baseless charges will keep young people’s lives on hold for as long as the courts drag on,” Mugo adds.

‘Warning is clear’

Experts say the state likely knows these charges will collapse but uses them as intimidation—sending a warning to Kenyan youths about the heavy price of protest, especially with the 2027 elections approaching as Ruto seeks a second term.

“These trumped-up charges are meant to make protesting unbearable,” says Ernest Cornel, spokesperson for the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC). “Terror cases come with bail terms most families can’t afford. They are also meant to isolate protesters—‘terrorism’ is a loaded word that breeds suspicion and distrust in their own communities.”

Mwau Katungwa, 27, was arrested at his home in Matuu two weeks after the June 25 protests. He says police identified him from a video showing him at a hospital helping his friend, 22-year-old Kelvin Mutinda, who was shot at the protest and later died. Katungwa was also charged with terrorism and spent a week in Kamiti prison before taking a loan for the 50,000-shilling bail.

Mwaura Katungwa faces terrorism charges but remains determined, vowing not to be silenced. Photo by Jaclynn Ashly.

“I cried a lot over this,” Katungwa tells TRNN. “On June 25, we were peaceful—just using our phones, fighting for a better country. Yet in the end, we are the country’s terrorists.”

Katungwa had been living with his extended family—his only surviving relatives—but they forced him to move out, fearing there might be truth behind the charges.

Wambua, a conductor on the matatus—Kenya’s shared minibuses—lost his job after his arrest. “People are saying I’m a terrorist, I’m a bad guy,” he says. “I think they worry bringing me back to work could put them at risk.”

For Katungwa, who does irregular construction work, and Mbindyo, both of whom took out loans to cover bail, the debt is mounting. Mbindyo says she must pay about 450 shillings ($3) a day in interest. “My mom only makes around 600 ($5) a day selling vegetables,” she explains. “That’s a huge burden for us.”

“I’m still carrying so much stress,” Mbindyo adds. “I’m afraid of people… If I talk to someone, maybe they’ll hear I’ve been accused of these things. So now I just keep my distance and stay alone. It feels like all of this is pulling me backward in life.”

Kabata points out that in a country scarred by hundreds of Al-Shabaab attacks that have killed thousands, branding youthful protesters as terrorists is particularly shocking. “Our communities are deeply sensitive to terror-related issues, especially homegrown threats,” he says. “To weaponize that against our own youths is simply immoral.”

Experts emphasize that the stigma these youths are confronting is deliberate and calculated—to sap young people’s will to protest and isolate them from their communities.

“As lawyers, we know for a fact the police have no evidence, but communities don’t—and that’s the point,” Mugo explains. “The stigma is devastating. Community members, especially business owners, unable to distinguish those arrested from those actually responsible for property damage, grow fearful or even hostile.”

“As lawyers, we know for a fact the police have no evidence, but communities don’t—and that’s the point,” Mugo explains. “The stigma is devastating. Community members, especially business owners, unable to distinguish those arrested from those actually responsible for property damage, grow fearful or even hostile.”

“Most of these young people lose their jobs with little chance of being rehired,” he continues. “Even if the charges are dropped, that label sticks. A terrorism charge brings instant unemployment and long-term exclusion.”

The situation is made worse by the fact that many arrested hadn’t even attended the protests. “In Kenya today, being young has become a criminal offense,” Kabata tells TRNN. “Anyone under 25 is treated as a suspect—rounded up and charged with absurd allegations.”

“The state is deliberately targeting those least likely to commit these crimes—peaceful, helpless youths—just to fit a narrative,” he adds. “The state is sending a message to parents: don’t let your children demonstrate, or they’ll be shot or slapped with serious charges.”

“The warning is clear—whether you attended protests or not, this is what awaits you if you ever dare to.”

The misuse of Kenya’s anti-terror laws also undermines national security, eroding public trust when Al Shabaab remains a serious threat. “If the government keeps misusing this law against critics, then when genuine terrorists are arrested, no one will believe it—it will just look like another ploy to silence dissent,” says HRW’s Namwaya.

Kenya receives substantial international counterterrorism support—over $700 million from the U.S. between 2010 and 2018—and was designated a Major Non-NATO Ally last year, cementing long-term security ties. While the Trump administration has cut health and food aid, its engagement with Kenya so far signals continuity in counterterrorism cooperation.

Experts warn that misusing anti-terror legislation risks undermining this support.

The weaponization of Kenya’s anti-terror legislation has already had an impact on demonstrations—this year’s Saba Saba protests in Matuu were nonexistent, as fear of terrorism charges kept people off the streets.

Still, many insist they won’t be deterred. “If there’s a protest tomorrow, I promise you I’ll be there,” says Katungwa, defiantly. “People say the youth are the leaders of tomorrow. Well, tomorrow has become today.”

“This is the generation that will make change in Kenya. Even if we are all charged as terrorists, we will not remain silent.”

This article first appeared on The Real News Network and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.