Copyright TIME

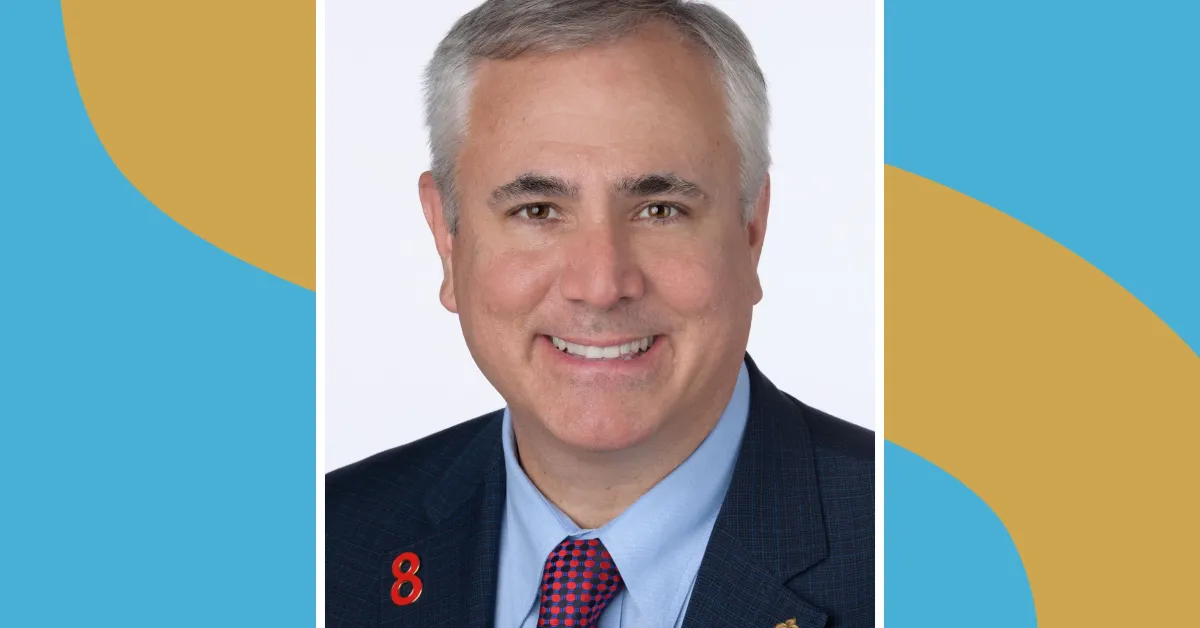

Most people might not have heard of the Framingham Heart Study. But the massive public-health research effort, now in its 77th year of conducting in-depth analysis of more than 15,000 people, is the source of many insights we now have into healthier aging. It inspired the first checklist for assessing heart disease risk, and our current understanding of how to reduce cardiovascular disease can be traced directly to its findings. While the Framingham Heart Study started off solely focused on heart health, following a large subset of the inhabitants of a former mill town on the outskirts of Boston throughout their lives, it is now providing information about the brain, liver, and many other organs. As part of TIME's series interviewing leaders in the longevity field, we spoke to epidemiologist Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, the current head of the study and a professor at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, about the study and what it tells us about aging well. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. What is the Framingham Heart Study? It’s the longest-running community-based study in the world. Its origins lie in finding the root causes of cardiovascular diseases, especially heart attacks and strokes. In 1948, the people who designed the study enrolled about a third of the population of the town of Framingham, Massachusetts, which is about 20 miles west of Boston. They really wanted to understand what was causing the emerging epidemic of heart disease after World War II. It was already the leading cause of death, but it was quite clear that it was on the rise, and it wasn't well-understood why that was happening. There were some very good hypotheses implying that diet and cigarette smoking might be linked, but it had never really been shown systematically or consistently. So Framingham is really the study that put what we now consider the traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease on the map. What happened next? They enrolled another 5,000-plus individuals who were the offspring of the original participants and the spouses of those offspring. So we're starting to get the genetic linkages, but also the environmental linkages—the shared environment between spouses. It was decades before we understood these things were important, but there were inklings, and they were smart enough to listen to those signals. So the offspring cohorts get examined about every four years, in addition to the first cohort being examined still every two years. That goes on through the 1970s and 80s and 90s. We start to understand more about not just total cholesterol, but the subcomponents of cholesterol. We start to understand more that it's actually your systolic blood pressure that's more dangerous for you than your diastolic blood pressure. Certain types of dietary factors, certain types of physical activity were better. There has been a huge explosion in the ways we can characterize people. And Framingham has really been a leader all along in understanding the process of aging in every organ system in the body. Yes, we are still the Framingham Heart Study, but we have just as much activity going on in brain health across the life course, and lots of activity looking at bone health, kidney health, lung health, liver health—you name it—because these people are so well studied across their entire life course. What kinds of things can people do to reduce the risk of diseases of aging? The American Heart Association has kind of a nice way to package this all together, called Life's Essential Eight. It’s a platform in which people can measure their cardiovascular health status today. It's also linked to really positive health outcomes over time, and it’s influenced by evidence from the Framingham Heart Study. Can we make the date that you get sick much later—much closer to the time you're going to die—so that you have more healthy years, not just more years, period? We don’t seem to necessarily be doing what the science suggests, as a society. Why is that? The truth is, although we've known that for 60 years, we're still terrible at implementing it in public-health policies and in clinical practice. It's a pretty simple message, but we don't design our society, our environment, our neighborhoods, or our food supply to optimize those things. It is possible to take this information and make a change. Great story: In the early 70s, Finland had the highest coronary heart disease death rates in the world, by a fair amount. They took information from Framingham and they said, You know what, let's design a study where we take a county with particularly high coronary disease death rates and we just make some public-health changes. We're going to implement smoking policy changes. We're going to help people quit. We're going to stop subsidizing meat, and we're going to start subsidizing fruits and vegetables in our food supply. They not only extended their lifespan; they extended their healthspan substantially. Genetics are not destiny. We can actually bend that curve, and people can do better if they can pursue these healthy lifestyle options. So much of this is actually in our control. But we need help: We need help from our food supply. We need help from good public-health policies so we are not exposed to indoor air that is contaminated by cigarette smoke. We need safe streets to go out and do physical activity. We need to actually be able to afford to buy fruits and vegetables. A lot of this is policy that sets the stage. But there's a lot in our control as well.