Scientists have 3D bioprinted miniature placentas, opening new ways to study pregnancy complications. The breakthrough comes from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS).

Pregnancy complications cause over 260,000 maternal deaths and millions of infant deaths every year. One serious condition linked to placental dysfunction is preeclampsia, affecting 5–8% of pregnancies.

Printing new pregnancy models

“Obtaining first-trimester placental tissue is not practical or safe, making early pregnancy challenging to study. By the time a baby is born, the placenta has changed so much that it no longer reflects what it was like in early pregnancy,” said Dr Lana McClements, the lead author of the study.

“Serious pregnancy complications like preeclampsia remain one of medicine’s great mysteries, largely because current animal and cell models cannot accurately replicate the human placenta,” she said.

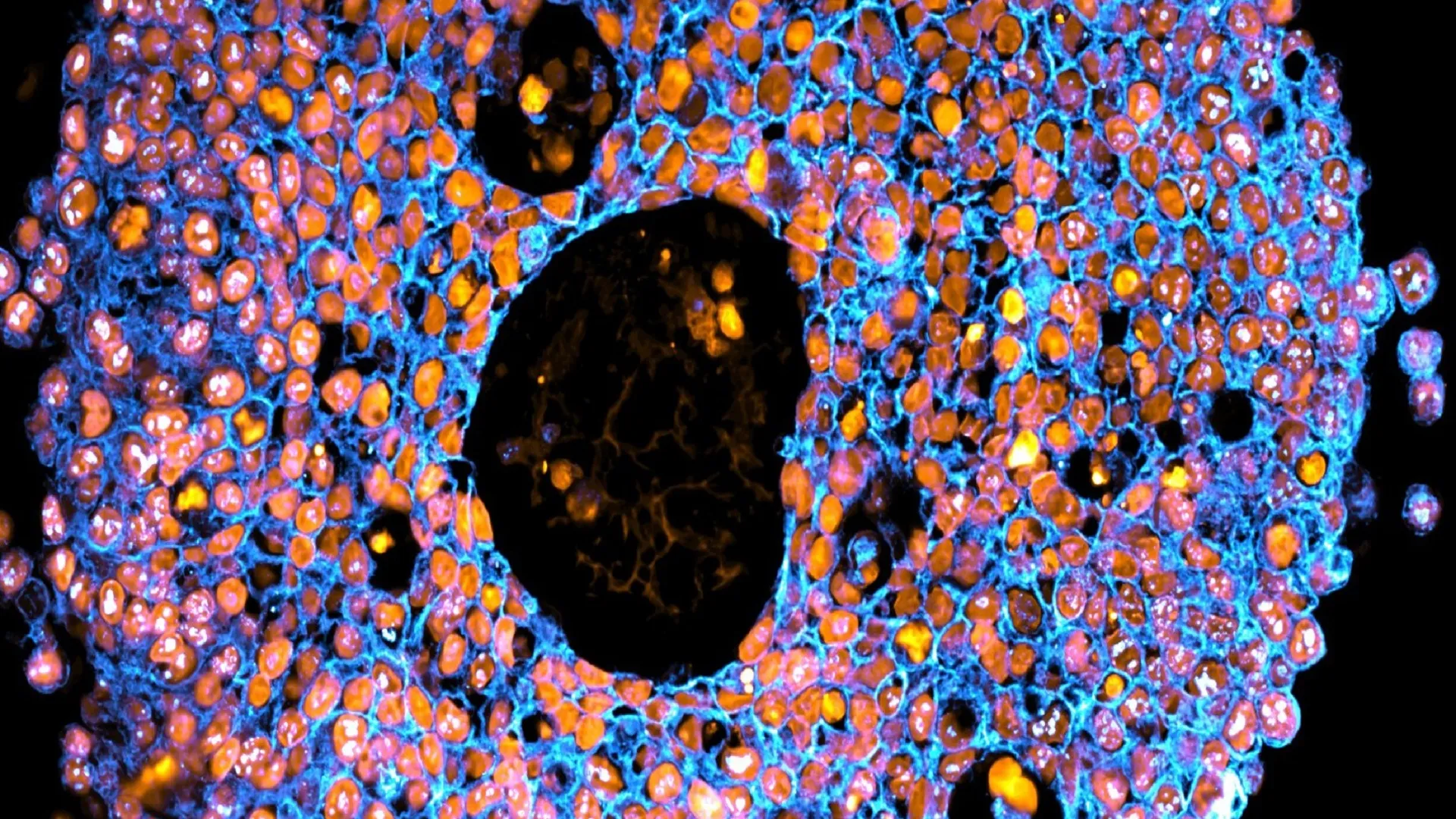

Miniature organs, called ‘organoids’, were first developed in 2009. They provide accurate models of human organs. Scientists grow them by taking stem cells and placing them in a gel that mimics tissue. The cells form clusters as they grow and divide.

In 2018, the first placental organoids were grown from trophoblasts – cells found only in the placenta. This marked a step forward in pregnancy research.

Bioprinting takes this further. It is a type of 3D printing that uses living cells and cell-friendly materials to create 3D structures. The UTS team mixed trophoblast cells with a synthetic gel. They printed them in precise droplets, much like an ink-jet office printer.

“Our printed cells grew into placental organoids and we compared them to organoids made via traditional manual methods,” said Dr Claire Richards from the UTS School of Life Sciences, who is also the first author the study.

“The organoids we grew in the bioprinted gel developed differently to those grown in an animal-derived gel, and formed different numbers of trophoblast sub-types. This highlighted that the environment organoids are grown in can control how they mature.”

Safer drug testing models

The bioprinted organoids closely resembled human placental tissue. This allows scientists to study the early placenta safely. It could help understand why some pregnancies go wrong.

“We showed these organoids were very similar to human placental tissue, providing an accurate model of the early placenta. This means we can start piecing together the puzzle of pregnancy complications and test new drugs safely,” Dr Richards said.

“For example, we exposed our bioprinted organoids to an inflammatory molecule found at high levels in women with preeclampsia, then tested potential treatments to see how the organoids grew and responded.”

The team hopes to refine these models further. The goal is a future where pregnancy complications can be predicted, prevented, and treated before they put lives at risk.

“As we refine these models, we move closer to a future where pregnancy complications can be predicted, prevented and treated before they put lives at risk,” said Dr Richards.

This breakthrough combines 3D bioprinting, organoid technology, and placental research. It may pave the way for safer drugs, a better understanding of preeclampsia, and lower risks for mothers and babies worldwide.

The findings have been published in the journal Nature Communications.