Copyright kyivpost

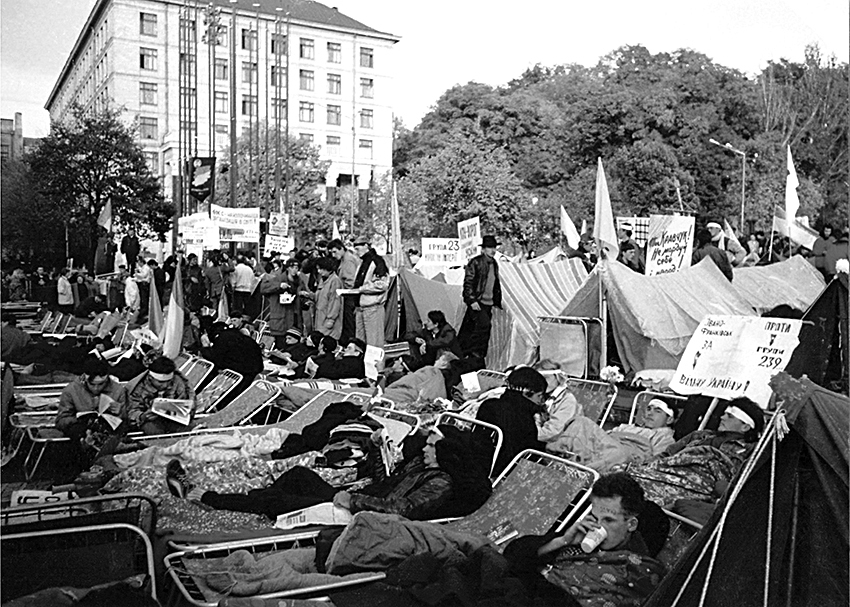

The first protest for democracy and national self-determination on Kyiv’s famed Maidan Square wasn’t the Orange Revolution of 2004, or the Euromaidan of 2013-2014. Less famous than those manifestations of popular resistance, this earlier protest in October 1990 was remarkable because it happened before Ukraine declared independence in August 1991, and more than a year before the Soviet Union collapsed. Scores of students set up a makeshift tent camp in central Kyiv and held a hunger strike until Soviet Ukrainian authorities caved and met most of their demands. They even forced the resignation of Ukraine’s Soviet-era prime minister. This successful act of nonviolent resistance became known as “the student revolution,” or “Revolution on Granite,” and it remains one of modern Ukraine’s most significant moments of civil resistance. What was behind it? By 1990, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) had unleashed forces the Kremlin could no longer control. The Berlin Wall had fallen in November 1989. Communist regimes across Eastern Europe were collapsing. The Baltic republics were moving toward independence – Lithuania in March 1990, followed by Estonia and Latvia. In Ukraine, democratic aspirations had been suppressed by local communist authorities under party chief Volodymyr Shcherbytsky. After his replacement in September 1989, Ukraine began to catch up. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic declared sovereignty on July 16, 1990, though the declaration was more symbolic than real. Many Ukrainians doubted their political leaders – including those in Rukh, a newly emerged democratic coalition – had the will for full independence. The Communist Party of Ukraine still monopolized power, and its leaders resisted change. The military draft kept sending young Ukrainian men into the Soviet Army, often to distant republics or conflict zones. Ukrainian remained marginalized in favor of Russian in public life, despite being the language of the titular nation. Schools taught a thoroughly Sovietized version of history that minimized Ukrainian national identity. The biggest worry? Gorbachev was trying to prevent the Soviet Union’s dissolution with a new Union Treaty. Ukrainian students had seen enough. Inspired by successful protests elsewhere in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, they decided to act. The immediate trigger came when the Ukrainian parliament postponed discussion of critical issues. Frustrated by what looked like political cowardice and endless delays, students from various Kyiv universities decided direct action was necessary. On October 2, 1990, the first group gathered in what was then called October Revolution Square (now Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square). The protest grew daily and earned its name from the granite steps and pavement where students camped out and held their hunger strike. The demands The demands were bold—revolutionary, even. The students wanted the Ukrainian parliament to refuse signing a new Union Treaty that would keep Ukraine in a reformed Soviet structure. They called for the resignation of Prime Minister Vitaliy Masol, whom they saw as a symbol of the old Soviet order. They demanded the nationalization of Communist Party property, which they believed belonged to the Ukrainian people. There was more. Ukrainian military conscripts should serve only on Ukrainian territory. Parliamentary deputies who had voted against Ukrainian sovereignty should face re-election. Student activists detained during earlier protests must be released, with guarantees that peaceful protest wouldn’t be met with repression. The students organized with impressive efficiency. Key leaders emerged—Oles Doniy from Taras Shevchenko National University and Markiian Ivashchyshyn became the public faces of the movement. They set up a coordinating committee to make decisions and communicate with media and officials. Supporters brought food, water, blankets, and other necessities. Speakers and cultural performances kept the square alive with activity. Security teams prevented provocations and maintained order. As days passed, the protest attracted attention from Kyiv residents, media, and cultural figures. Workers from several major industrial plants began considering their own support. Talk of a general strike was in the air. The authorities took notice. Behind the scenes, negotiations intensified. Government officials, including Verkhovna Rada Chairman Leonid Kravchuk, met with student leaders to hammer out compromises. On October 17, after 15 days – with weakened hunger strikers receiving medical treatment – a breakthrough came. The Ukrainian parliament, responding to mounting public pressure, agreed to most of the demands. Masol resigned. The parliament postponed signing the new Union Treaty, keeping Ukraine’s options open. It committed to ensuring Ukrainian conscripts would serve within Ukraine’s borders. It agreed to consider nationalizing Communist Party property and to guarantee the right to peaceful protest. The students had won. Through peaceful resistance, moral courage, and sheer determination, they’d forced the government’s hand. The Revolution on Granite effectively transformed Ukrainian civil society and political culture. It demonstrated that, after the abandonment of totalitarianism, peaceful protest could succeed, and that ordinary citizens – especially young people – could shape political outcomes. It encouraged others to be bolder in pressing for Ukraine’s independence and democratic future and emphasized that there could be no turning back.