Copyright The American Conservative

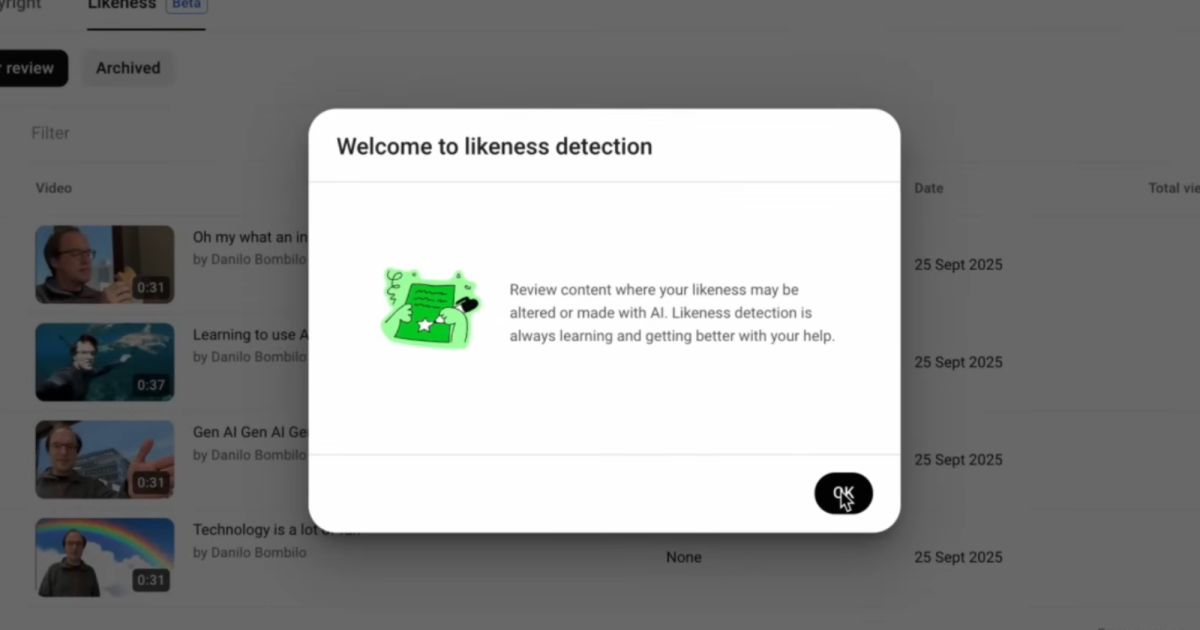

Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player... This article is the first of two parts. Keeping an AI on the Centennial Four years from now comes the hundredth anniversary of one of the most momentous events in American history: the stock market crash that began on “Black Thursday,” October 24, 1929, and was followed, of course, by the Great Depression. Historians and other scribblers will help us to recall those events. As always, they will spin them in keeping with their own mental maps. Yet now there’s a new motive force, with its own motives: artificial intelligence (AI). In the bleakest years back then, 1929 to 1933, national income fell by 30–40 percent and unemployment rose to nearly 25 percent; in fact, joblessness lingered above 14 percent until 1941. That extended disaster scarred and changed Americans. During the decade of the 1930s, the country was transformed from celebrating free enterprise and exalting self-reliance to fearing business and embracing paternalism. In terms of partisan politics, the change was equally profound. After Herbert Hoover’s presidency ended in landslide defeat in 1932, the Republican Party did not win the White House for a full two decades. Indeed, if we consider the 18 presidential elections from the inception of the Republican Party in the mid-19th century through 1928, we see Democrats winning just 28 percent of national ballots. Yet then, beginning with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s victory in 1932, the Democrats’ win-percentage almost doubled, to 54 percent. Over the same near-century, Democrats have had the edge in Congress as well. Cui Bono? So we’ve already answered that cynical question of the Romans: Cui bono? (Latin for “who benefits?”) Yet in addition to the Democratic Party, there was another beneficiary: the federal government. During the 1930s, the small peacetime government became permanent big government. So there’s another cui bono. Of course, the Democrats are the Party of Government. That was not the case in Thomas Jefferson’s day, but it was definitely true by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s time, and since. So we’ve seen a convergence of party and state. Now we can add a third converging force: ideology. The expansion—sometimes to the point of totalization—of the state has been the cause of the left over the last couple centuries. So it all comes together: Democratic partisanship, big government, and progressive believing. Those convergences harmonized in 1929 and into the 1930s. Was this just good luck for the Democrats, bureaucrats, and the left? After all, just because one interest benefits from an event doesn’t mean that it has had a role in causing the event. Yet it’s often true what they say: Luck is the residue of design. In the decades that followed the Depression, Democrats exploited their good fortune. Partisans waved the proverbial “bloody shirt,” reminding voters that Republicans were the party of Hoover and hard times. Who could blame them? Victory-minded pols always play the best cards they’re dealt. Updating this opportunism, contemporary Democrats advise: Never let a crisis go to waste. Yet the received memory of 1929 as a Republican debacle—followed by the heroic role of the Democrats, beginning in 1933, to rescue the country—has been much more than a matter of political speeches and platforms. In fact, there’s been a full-spectrum effort—not just pols, but media, intelligentsia, academia—to convince the country that big government and progressive thinking were not only vital to national salvation then, but are integral to the commonweal now. Indeed, the federal leviathan itself has been enlisted in the cause of its own engorgement: spending money, fueling dependency, supporting activism, subsidizing propaganda. All this has worked out well for the superstate: In 1929, the federal government spent less than 3 percent of GDP. In 2024, it spent more than 23 percent—that’s the highest peacetime percentage ever. Yes, waves of anti-government populism and backlash have washed over American politics in the past century and have even won some victories, but the big bones of the beast are still intact. It’s possible that 2025 will show some state shrinkage, thanks to Donald Trump, DOGE, and Russ Vought, but the difference will be shavings. No wonder Elon Musk has, at times, been so irate. Interestingly, the left isn’t happy, either, with the status quo. It has wanted a much bigger edifice. In the past, in the name of socialism or communism; more recently, in the name of environmentalism or anti-racism. Yet now the left, questing as ever, hopes to enlist a new kid on the block: AI. By common agreement, AI is going to affect everything. And because AI is so all-encompassing, it’s already proving to be a subtle but steady advocate for liberalism. This can be illustrated through a single case study, presented here: how Google AI answers questions about the Crash and the Depression, aiding the related causes of Democratic victory, federal aggrandizement, and lefty teleology. If we’re not mindful of this AI force, we could find ourselves at some new Finland Station. Yet before we look ahead to the digital landscape being 3-D printed in the 21st century, let’s look back to analog paths grooved in the 20th century. An October to Remember Come October 2029, we will see many retrospectives, and much commentary, about the Crash and the deep slump that followed. Indeed, one consequential work is already here: Aaron Ross Sorkin’s 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History—and How It Shattered a Nation. That volume is heavy on action (scandals and scapegoats) and anecdotes (during those disastrous days, Winston Churchill was in the NYSE gallery as stocks plummeted and as a disconsolate broker, too, plummeted 15 stories). Yet mainstream media reviewers have been quick to tease out larger themes and point to perceived silver linings. Bloomberg News opines, “It’s always enjoyable to puncture Wall Street’s self-regard”; seeing further that the crash “added to the political momentum leading to the establishment of the Securities and Exchange Commission and other reforms for Roosevelt’s first term.” (Emphasis added.) Beyond Sorkin’s book, it’s fair to anticipate we’ll see much more of this liberal-leaning discourse over the next few years. The dominant narrative coming from the mainstream media—and now, alongside it, AI—will be this: The culprits were, and are, unregulated greed and laissez-faire. Per this narrative, the deeper fault is misplaced faith in free markets and “rugged individualism” (complete with sneer quotes). The preferred solution will be what has been: bureaucratic regulation, Keynesian economics, an engrossed state. We know this because we’ve seen it before. A half-century, ago on the 50th anniversary of the Crash, the narrative was in full force. In Fall 1979, Sorkin’s newspaper, the New York Times, then and now the single most influential narrator, published a score of articles on the Crash. Many pieces recalled the drama and, at the same time, offered homilies—the “better” policies that had been put in place. For instance, on September 23, 1979, the Times headlined, “From Binge to Bust: The Legacy of the Crash,” reporting, “Wall Street has been wrapped in the web of the Government overseers—the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Reserve—which have so far succeeded in preventing the worst of the abuses of the 20’s.” So that’s the takeaway: The federal government helps, it’s good, it saves. Sometimes the coverage edged into outright cui bono. For instance, on November 1, 1979, liberal economist Robert Lekachman, author of The Age of Keynes, was quoted: “The Depression was the most wonderful thing for young lawyers, economists and Ph.D.’s who didn’t have a clue about how to find a job and then suddenly they were in Washington running the country.” Okay, that sounds a bit like New Deal as self-deal, but Lekachman saw a happy ending: the “permanent impression that we are capable of managing the economy and that the government can do a whole lot of good.” Such commentary helps explain why the liberal Keynesian narrative has been so popular among liberal Keynesian careerists. In fact, the loquacious Lekachman was a go-to figure for the Times. In the 1980s, he authored two books, Greed Is Not Enough: Reaganomics, and Visions and Nightmares: America after Reagan. So it’s little wonder that in 1987, in the wake of an epic one-day stock market plunge, the Times was happy to quote him once again, muttering doomy thoughts: As a result of Mr. Reagan’s blatant appeal to the greed of his constituency, the most affluent 10 to 20 percent of the population, we got not the promised surge of new investment but a binge of wasteful consumption, profiteering in real estate development and stock market manipulation, none of which has improved the situation of the United States in world markets. In fact, the economy was doing fine under Reaganomics; real GDP grew by a third, and the Dow Jones average more than doubled during the Reagan years. Indeed, hiccups and all, the country has flourished these past four decades. Still, Lekachman-esque nattering has remained steady at the Times; Paul Krugman spent a quarter-century on the op-ed page, snarling at anything Republican. Now we’re starting to see how liberal-left groupthinkers have supervised the national conversation this past century. Like-minded chatterers fanned out across not just editorial pages, but also bookstores and bureaucracies—public, philanthropic, and corporate. To be sure, in the past few decades, alternative media have given rise to vigorous voices on the right. Yet now, as an aid to the left, AI looks to be the deus ex machina. Generating History Today, when Americans seek answers online, they increasingly see AI. Often, generative summaries—a paragraph or two on whatever topic—appear unbidden. In fact, people like the AI summaries well enough; they now rate as the way most gather information. So AI answers are already shaping the discussion, limited as it might be, about the events of 1929. We’ll take a closer look at Google AI’s answers about the Crash and the Depression in Part Two, but for now, we can speak to Google itself. It’s no secret that the Silicon Valley behemoth has not only leaned left, but also pro-Democrat. Earlier in this decade, Google was happy to censor, even shut down, expressions that hurt liberal feelings. Indeed, as recently as 2024, a thoroughly woke Google was offering us AI-made images of black Vikings, Popes, and Founding Fathers. Of course, Donald Trump’s victory last year has left the woke chastened. In September, Google issued a mea culpa for some of its past misdeeds; as compensation, its YouTube subsidiary agreed to pay Trump entities $24.5 million. Yet has Google truly changed its lefty ways? Or will it revert back when it thinks the heat is off? In September 2025, Wired magazine’s veteran tech chronicler, Steven Levy, observed that, while some tech lords had moved right, “The community still overwhelmingly leans left.” So rank-and-file Googlers might still be up to their old tricks. In fact, recent Google searches reveal plenty of bias. And the Daily Caller’s John Loftus looks ahead to 2026: “Ahead of a crucial midterm election, tech giant Google is ramping up its mind control efforts and censorship agenda against conservatives and right-leaning news outlets.” Writing for the Cato Institute earlier this year, Andrew Gillen agrees on Google’s continuing blue tilt. Some of it, he finds, is “human interference which designs the models to give left-wing answers.” Then Gillen adds a subtler point: Google’s AI, and all AIs, are functions of their “diet.” They are what they “eat.” In Gillen’s words, The raw data could be the second source of bias in the AI models . . . more left-leaning written content, which would then lead to AI models trained on written materials to reflect that left-leaning bias. He continues, Consider an AI model trained on newspaper articles over the last decade. Such a model would have a leftward bias due to suppression, censorship, and advertiser boycotts of right-leaning publications and content. To the techie motto “garbage in, garbage out,” we can add, liberalism in, liberalism out. So maybe we’re in a sort of input race. Unfortunately for the right, at least since the Russian Revolution—and probably since the French Revolution—progressives have written more. Or, if one prefers, propagandized more. By any name, the left has the edge on content-providing. For instance, Howard Zinn, a onetime member of the Communist Party USA, went on to author the hugely influential People’s History of the United States. Having sold some 2 million copies, the textbook helped indoctrinate one-fourth of all high school students in Blame America First. Zinn knew what he was doing; to him, history is “not about understanding the past,” but rather, “changing the future.” So our thoughts turn to George Orwell’s snappy dictum from 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” So yes, those who have interpreted 1929 will also have the edge on interpreting 2029. The Tower of B(AI)bel Oh, and one more thing to keep in mind: For all the pretenses of AI toward depth, it’s shockingly shallow. Google has been proclaiming for three decades that its aim is to organize the world’s information, and yet it only skims the surface. In 2025, the tech consultancy Semrush surveyed the sources used by Google AI. These sources are, literally, the feed stock for those generative summaries. And the number one source for Google is —Reddit. That’s the hip social-media platform that focuses on questions, answers, and niche interests. Reddit has been in the news a lot, in the wake of the assassination of Charlie Kirk. Two days after the slaying, a classmate described the accused shooter as “a Reddit kid.” Utah Governor Spencer Cox confirmed the connection: “Reddit culture and these other dark places of the internet where this person was going deep,” and that, in turn, imbued the shooter with a murderous “leftist ideology.” Indeed, the predominant leftiness of Reddit was foretold years ago. In 2020, as Donald Trump was running for re-election, Reddit banned a pro-Trump subreddit, r/The_Donald. That niche destination was the largest pro-Trump forum on the internet, so it must’ve been a moneymaker; yet Reddit dubbed it “hate speech” and shut it down. If you’re still curious, you can visit the X feed, Reddit Lies. That source may or may not convince you that Reddit tells untruths—plenty of threads are thoughtful and factual—but it will surely convince you that, overall, the site leans left. With apologies to the Roman poet Juvenal, we can ask: Who will edit Reddit? The answer seems to be, No one conservatives should trust. So now to the second largest source for Google AI: Wikipedia. For the most part, Wikipedia is unobjectionable, even admirable: Aided by buffs who care and share about favorite topics, it has further vacuumed up information from public-domain works—many of which are, of course, classics. Yet at the same time, on some topics, not unlike Reddit, Wikipedia’s wokeness is both legion and legend. Can Google tell which from which? Next up, source-wise: YouTube, Google itself, and, uh, Yelp. Now of course, Google’s bread-and-butter is e-commerce. And for that, Yelp is invaluable. By contrast, Google’s forays into intellectual and academic research—the sort of delving that would teach about 1929—are afterthoughts. And it shows. A look at Google’s top 20 sources—pretty chart here—tells us that precisely none of them are, say, the Library of Congress. Indeed, it’s hard to find books anywhere in Google’s AI armamentarium. Moreover, as one clicks around, one sees no sources that are behind paywalls, e.g. the Wall Street Journal, Dun & Bradstreet, or a million scientific journals. What we see instead are non-paywalled journalistic outlets—Al Jazeera, the Guardian, HuffPost, etc.—most of which tilt left. The same pattern holds true for institutions, such as universities, think tanks, and advocacy groups. Their content, too, is free, and Google likes that. And if these sources, too, lean left, Google laps them up. It gets worse: According to one estimate, 57 percent of all the material on the internet is AI-generated. That number has been disputed, and yet it’s undeniable that AI-generated “slop” is proliferating with the speed of, well, Moore’s Law. Indeed, Gresham’s Law is taking hold—the greater quantity of lower-quality content is driving out higher-quality content. And as we have seen, the higher content isn’t so high. Once upon a time, when publishers put together, say, dictionaries, encyclopedias, or journals of record, they took pains to assemble mastheads and advisory boards composed of scholars and other worthies. Yet today in Silicon Valley, advisory boards of any kind are vestigial. So maybe we shouldn’t trust these AIs, and/or the people making them. Okay, let’s come back to 1929—and 2029. A century ago, the stock market economy crashed, the economy tanked, and America suffered for more than a decade. So now, nearly a century after the Crash, do we know which specific policies back then helped, and which hurt? Beyond a buzzword or two, do we even know what the policies actually were? There can be many answers to these questions. Yet as we shall see, AI is shrinking the number of answers. One might say that some responses just don’t compute. Perhaps purposefully, AI is narrowing the Overton Window of possible policy solutions. Since we see this pattern repeating and repeating, we can surmise that it’s not random—it’s a hive-minded movement. Indeed, if we get the feeling that we’ve been herded, we might wonder if we’ve actually been bamboozled. It’s too late to change the past, but at least we can understand it better, eyeing the cui bono. Then we can resolve: Won’t get fooled again. Is this too harsh a take on the current information environment? In Part Two, we’ll put this question to an expert.