Copyright popmatters

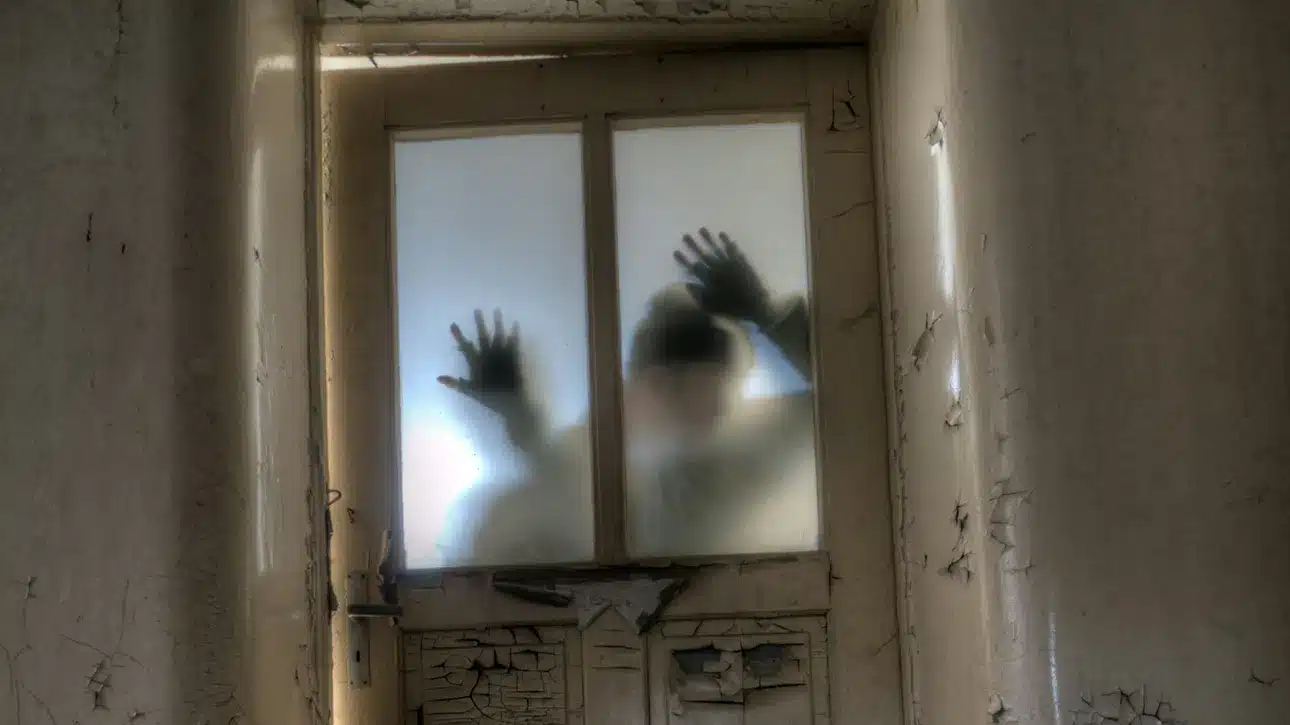

I love Halloween. I’m not much for the holidays in general, but this old pagan holiday gets me. Part of that love, mind, is this opportunity to explore the darker facets of our being – both individually and socially – through art and interaction. Horror literature and, yes, film, are windows into things we otherwise tend not to speak about. That journey, that self-exploration, in spite of the risk of finding things we might not want, is key. So too are allegories in horror, which show us something about ourselves and our society. Although horror often receives a reputation for cheap production, exploitation, and cheesy acting (such films generally offer easy profits for studios), it is an important expression in cinema. Horror as a genre has a long and storied film history which began well before what modern audiences might traditionally identify as a “horror movie”, whether in the form of existential horror (tell me there aren’t horrific elements in Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 masterpiece, Ikiru), psychological horror (which some early noir romances such as Charles Vidor’s 1946 Gilda arguably had their hand in), various kinds of experimental film making (Luis Bañuel and Salvador Dali’s surrealist 1929 Un Chien Andalou), indie projects which – while not exactly art house – had a tremendous influence on cinema and pop culture as a whole (George Romero’s 1968 Night of the Living Dead), or even films ostensibly for children which ultimately contributed tremendously to the evolution of cinematic horror (Walt Disney’s 1937 animated classic Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, itself an adaptation of a disturbing Grimms’ fairy tale). In celebration of ‘All Hallows’ and recognition of the horror genre’s importance as a mode of deep-seated cultural expression, PopMatters presents this list of 13 films that stirred, inspired, and yes, terrified our staff. These 13 films – some well-known, some less so – all found ways to either cement themselves in film history, develop horror movies as a genre, tell us something important about ourselves, or simply (and thrillingly) scare us silly in ways that mattered more than we first realized. – Alex Lindstrom Nosferatu and the Vampire as Parasite From which aspect of the psyche do tales of horror manifest? The horror tale’s prevalence across cultures and eras evinces the servicing of a deep-seated (if unidentified) human need. It is therefore no surprise that horror became integral to the commercial film industry not long after it began in the 1890s, with numerous vampire films among those early releases. F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), an unauthorized silent film adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), was not the first vampire horror movie (that goes to Robert G. Vignola’s 1913’s The Vampire), though it is surely the earliest one to leave such an enduring mark on popular culture. Max Shreck’s brilliant performance in the title role exudes an aura of pure malignancy, but the more culturally dominant post-Nosferatu versions of Dracula have tended to be suave, sophisticated, and graceful (though still nefarious); Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee come to mind. It’s from these more charming on-screen depictions that the ultra-hip, seductive creatures of Anne Rice and her imitators are ultimately derived. Despite this, Nosferatu has maintained a cultural presence of its own. Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot (Doubleday, 1975; TV miniseries in 1979 and 2004) pays homage to Nosferatu, as does E. Elias Merhige’s Shadow of the Vampire (2000), a metafictional depiction of the making of Nosferatu in which Max Shreck (portrayed by Willem Dafoe) happens to be an actual vampire who preys upon fellow cast members. With no patina of attractiveness for its title character, 1922’s Nosferatu emphasizes the vampire’s nature as not just a predator, but a parasite. The vampire is grotesque, deformed, and unmistakably evil. There’s no mitigating factor, no charming narcissism a la Anne Rice’s Lestat, no doubt here as to where that line between good and evil lies. In today’s cinematic world of ambiguous anti-heroes and quasi-villains, this nearly century-old classic horror movie provides a refreshing ‘change’ – and striking viewing experience – to this day. – Arthur O’Keefe The Wizard of Oz Evokes all the Emotions that Horror Movies Trigger One of the most influential horror movies for several generations of Americans was broadcast annually on US television from 1959 to 1991 as a highly promoted “special” targeted at children as a family-fun movie. Some children, however, may have found it more terrifying than delightful. The story of an orphan being raised by her neglectful aunt and uncle, as she longs for a better life, is transformed in Victor Fleming’s 1939 The Wizard of Oz, which dumps Dorothy and her dog into a fantasy land of friendship, hot air balloons, magic… and horror. The Wicked Witch of the West, portrayed with a curdled voice by Margaret Hamilton, is a terrifying villain and, in every sense, a classic horror figure, driven by a murderous vengeance for the death of her sister. Like so many other horror figures, she seemingly appears here and there around “random” corners of the film. Kids anticipate the worst: Dorothy will have to kill the Wicked Witch or be killed in turn. For so many of us, there was one scene that provoked gut-wrenching horror at every showing: the witch captures Dorothy and Toto with a flock of winged monkeys. “Fly, my pretties, fly!” she screeches. They carry off the Kansas duo while dismantling the film’s most affable character, the Scarecrow. Those monkeys, bat-like and fluttering down from above, evoke all the emotions that horror can trigger: irrational fear, relentlessness, and inevitability, that sense that you cannot escape. Though they carry no obvious human element, they also suggest some pathos—they are slaves to the witch, not quite rational actors but semi-intelligent tools of death and dread. In a 2016 Rolling Stone interview, Robert Eggers, the director of 2016’s The Witch, traced the inspiration for his film to recurring dreams of witches and dark woods he had during a childhood marked by the horrific imagery of The Wizard of Oz. Dorothy’s defeat of the Wicked Witch leads to a seemingly happy ending, yet her triumphant return “home’ is to a group of adults who doubt her. The unease of that return is amplified by the knowledge that those proverbial flying monkeys are still out there in the sky somewhere, ready to dive down and grab me. – Will Layman The Innocents Plants Disturbing Seeds of Doubt Evil has never been quite so exquisite as in Jack Clayton’s gothic dream of a horror movie, The Innocents (1961). This unsettling adaptation of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1898) is a breathless exercise in economy, brevity, and ambiguity, and perhaps the most perfect model of psychological horror ever put to film. To call The Innocents a “ghost story” is almost insulting. There are no gimmicks, no blood, no monsters. Everything is, in fact, quite beautiful. From the idealistic governess (Deborah Kerr) to her two new charges (Martin Stephens and Pamela Franklin) to the gentle fields of their remote corner of Victorian England, the screen shimmers fairly with hushed eloquence. There are, however, demons. Of a personal nature. It doesn’t take long for Miss Giddens (Deborah Kerr) to realize something’s rotten in the county of Essex. The increasingly unsettling behavior of the children, coupled with paranormal voices and apparitions in the house, lead her to believe the children are being possessed. Truman Capote’s adaptation of James’ novella (as co-writer) is seductive and subtle. He refuses to pander to the viewer and forces us to participate on a startlingly intimate level. Seeds of doubt sewn cleverly early on keep us on an emotional pendulum. Is the governess of sound mind? Are the children possessed? Are they “innocents”? Indeed, is she an innocent? As the questions swirl, Clayton simmers the suspense to a boil. He commandeers this ghostly vessel of a horror movie with skillful restraint, giving Kerr a blank canvas on which to paint the most complex, captivating performance of her career. In Sir Christopher Frayling’s exploration of The Innocents (titled same, BFI Film Classics, 2013), he describes an exchange between Deborah Kerr and director Jack Clayton: said Kerr, “I remember saying to Jack ‘do you think she really sees these spooks or is it all in her mind?'” “You make up your mind,” replied Clayton. – Carley Hildebrand The Shining Sets the Rabid Id Loose I have seen Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 psychological horror movie, The Shining, three times. The first time was with friends, without our parents’ permission, when I was about nine. Danny (Danny Lloyd), the young boy with the strange power dubbed “the shining”, seemed roughly our age. When he talks with his hand and calls his pointer finger “Tony”, it is absolutely terrifying. Worse is the supernatural images of the twin ghost girls and the woman-turned-ghoul in the bathtub. We were made scared of bathrooms for years afterward. The second time was about a decade later, to see what all the fuss in my child’s mind had been about. This time, The Shining read as a black comedy about writer’s block and isolation; it was less about Danny and bathrooms than about Jack Nicholson’s madcap persona and the ridiculous haunted-house conventions. A hotel built on an Indian burial ground? I laughed at the film, at Jack, and at my childhood self for being scared of a joke. The third time was recently. Now married with three kids of my own, The Shining is even scarier than when I was nine. I found little of it to be supernatural, and nothing about it to be funny, unlike my smug college self. Instead, I now see The Shining as a harrowing psychodrama about heinous domestic abuse, the not-at-all-funny ways in which women and children are most threatened by – and indeed most likely to be murdered by – their husbands and fathers, their supposed protectors. Without society or support, Jack has nothing to rein in the impulses of his rabid id. Certainly, not all men try to murder their families with an axe, but that would rather miss the point here. Like a wizened philosopher, horror knows who we are, but like an axe murderer, it also knows where we are hiding. – Jesse Kavadlo Lisa and the Devil‘s Morbidly Elegant Metaphysical Hell Casual horror movie fans usually identify Italian horror cinema with films directed by luminaries such as Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci. However, it’s safe to say that these two directors were heavily influenced by the macabre aesthetics of Mario Bava, the first and foremost master of “spaghetti horror”. Even though Bava is better known for Black Sunday (1960) and Planet of the Vampires (1965), Lisa and the Devil (1974) may well be his most inspired horror film in a directorial career spanning 33 years and 37 movies. Because of its dream-like structure, nightmarish plot, surrealist atmosphere, and lyrical staging, Lisa and the Devil may challenge those unfamiliar with Bava’s artistry. On a personal side, I was utterly bored and sorely disappointed the first time I watched this flick, but a few years later, Lisa and the Devil would become my favorite Bava film. Arguably, it takes considerable proclivity for the genre and a kind of “calm” to fully appreciate the many intricacies of this criminally underrated horror movie’s morbid elegance. As the legend goes, after failing to secure a distribution deal, producer Alfredo Leone decided to re-shoot and re-edit Lisa and the Devil to make it look like a film in the vein of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). Hoping to cash in on the popularity of Friedkin’s groundbreaking film, Leone completely reconstructed Lisa and the Devil to feature the story of Lisa’s possession and the priest’s efforts to perform an exorcism. The resulting travesty was aptly renamed The House of Exorcism (1973) and was an unfathomable commercial and critical disaster upon its American release in 1975. Lisa and the Devil is a gorgeously shot horror movie set in a metaphysical hell where logic breaks down in nightmarish ways, but its ambiguous storyline leaves the viewer pondering long after it’s over. Mysterious, creepy, and beautiful, Lisa and the Devil is required viewing for the serious horror movie fan. – Marco Lanzagorta Eraserhead Torments with Narcotic Fever Dreams Before slithering into cinema legend via the late ’70s midnight-movie circuit, David Lynch’s 1977 classic Eraserhead began as a student project on a shoestring budget. When not scavenging donations to fund his horror movie, Lynch survived by delivering the Wall Street Journal by day and sleeping (illegally) in the unused stables on the film’s set at nightfall. After its five-year existential struggle, Lynch’s resilient project began rattling audiences with its cryptic montages and woozy sound design. For lovers of black comedy, Eraserhead features a surreal encounter between the iconic wild-haired lead, Henry Spencer (Jack Nance), and his reanimated chicken dinner oozing blood between its twitching legs. In Lynchian fashion, Eraserhead‘s plot comes second to the atmosphere, to total immersion in his narcotic fever dreams. Spencer and his troubled ex-fling Mary X (Charlotte Stewart) struggle to take care of their sickly mutant baby, a rubbery, beady-eyed anomaly resembling a cross between E.T. and a limbless Gremlin. When not tending to their ever-wailing child, Spencer searches for peace, weathering the seductions and eruptions of a maddening and bleak industrial world. Contrasting the vulnerability of youth with the menacing forces of nature has become a trope of the horror genre (e.g., Stranger Things). Instead of externalizing opposing forces, Eraserhead envisions innocence and power as facets entwined within oneself. In light of contemporary social justice movements addressing abuses of privilege (think #MeToo) – not to mention the global rise of nationalism (think Brexit) – the world we share now is facing the terror we have raised, the terror we have made for ourselves. Lynch’s child-horror movie perfectly expresses both the sources and the consequences of our humanity; there is no escape. The swaddled monster’s creation is itself a mystery; Lynch bound his crew to confidentiality on the matter. Whether mechanical or animal, its exact makeup will remain unknown. Lynch loves the riddle of the unexplained. Hs fans continue questioning Eraserhead‘s darkness. – Todd B. Gruel Halloween Drags in the Golden Age of the Slasher The unstoppable and vaguely supernatural killer. The flashing knife and the teenage babysitter in danger. The “final girl” who fights the “monster” to the death… but then we learn the monster isn’t actually dead. All these elements, or tropes, are familiar to horror audiences and have been for almost 40 years, but they wouldn’t be if not for John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), the independent horror movie that started the golden age of the slasher. Carpenter had already made the dark tale Precinct 13, a cult film that melded the western with George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. Shot on a limited budget but with the production capital of actor Donald Pleasence (as Loomis), Carpenter’s Halloween gives horror fans a story of babysitters in danger and quiet suburbs under threat. Framing the events with America’s favorite pagan holiday, Michael Myers (referred to as “The Shape” in the script and closing credits for his fully adult incarnation) transformed American horror movies. Otherworldly evil… stalking the streets of your own neighborhood. Halloween likely found the audience it did because of a number of cultural anxieties, or rather, obsessions, of the late 1960s into the ’70s. Media sensationalism convinced many that 31 October was returning to presumably dangerous centuries-old roots, a time when tricks were much more common than treats. The late 1970s also proved ground zero for the birth of modern urban legends, many of them issuing directly from broader social concerns about the dramatic and indeed revolutionary changes of the ’60s. Worries about the ‘younger generation’ took the form of stories about Halloween treats turned into deadly weapons. Razors appearing in apples. Powdered sugar, which is actually corrosive lye. American culture was fertile ground for exactly the kind of horror story Carpenter wanted to tell, and as those sensationalized anxieties surrounding trick-or-treating continued well into the 1990s, you can be sure Carpenter’s Halloween had a hand in it. – W. Scott Poole The Thing Infects the Audience with Paranoia John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) was savaged upon release. Writes the New York Times‘ Vincent Canby in 1982, “The Thing is a foolish, depressing, overproduced movie that mixes horror with science fiction to make something that is fun as neither one thing or the other. Sometimes it looks as if it aspired to be the quintessential moron movie of the 80’s – a virtually storyless feature composed of lots of laboratory concocted special effects, with the actors used merely as props to be hacked, slashed, disemboweled and decapitated…” Canby was far from the only one to find Carpenter’s horror movie distasteful, perhaps particularly as it was a remake of Christian Nyby and Howard Hawks’ thoroughly classic 1951 original but with gore effects dialed up way past 11 (though not without thematic cause). Just how deeply confusing, infuriating, and even embarrassing Canby’s review reads today is a testament to the staying power of Carpenter’s masterpiece, a work which has been eagerly hailed as one of the best horror movies ever made, bar none, with increasing regularity for at least the last two decades. The story of a remote Antarctic research team that “finds something in the ice” is not only more faithful to John W. Campbell’s Who Goes There (1938), but remains astoundingly influential to this day. In a 2016 Telegraph interview, Quentin Tarantino said of the film, “It was the way I felt watching The Thing the first time I saw it in a movie theatre… I just really connected to it. This crazy suspense leads to terror to a place suspense rarely ever gets to… The paranoia amongst the characters was so strong, trapped in that enclosure for so long, that it just bounced off all the walls until it had nowhere to go but out into the audience. That is what I was trying to achieve with The Hateful Eight.” Tarantino similarly notes within the interview how this claustrophobic film experience influenced Reservoir Dogs (1992). It’s hard not to gush about Carpenter himself when talking about his films. Carpenter’s indie cred remains despite his legendary status, a thoroughly “working-class” director who held his chin high amid many industry disappointments, put-downs, and challenges. Today, I suspect, he enjoys watching his work grow in the recognition it so richly deserves as an integral part of American film history. – Alex Lindstrom The Witches Lures Children to Its Horror Movie Cottage Ostensibly a children’s film, Nicolas Roeg’s The Witches casts a harsh light on the world that I never expected when I first saw it as an impressionable four-year-old. In the film, a young boy named Luke (Jasen Fisher) is put through the emotional ringer. After his parents die in a car accident, he must abandon his life in Norway to live in England with his grandmother Helga (Mai Zetterling), a diabetic chain-smoker with deteriorating health. If it wasn’t enough that he might lose every family member he has, Luke learns that witches exist, these evil beings that hate children and want nothing more than to see them wiped out. Helga tells Luke about how witches operate, depicting them less as spellcasters and more like child predators murdering kids and damning their souls for eternity. All of this happens in just the first act of this horror film, and that’s before the witches’ plot to kill all the kids in the world by turning them into mice. The Witches scared the hell out of me at a young age, yet it also comforted me, strangely. It didn’t coddle me, didn’t play nice with its younger audience. I felt that it treated me like a person who would one day grow up and face a lot of ugly, scary elements in life. As I became an adult, I kept coming back to horror because, time and again, the genre confronted topics many mainstream movies couldn’t or wouldn’t face, casting light on many a terrifying idea in ways both provocative and entertaining. Can you imagine mainstream dramas with the same heavy, existential themes as Ari Aster’s Hereditary or Jordon Peele’s Get Out finding the audiences they did and, if not able to dress themselves in the genre trappings of horror, pointedly conveying their cultural criticism? As mainstream movies become increasingly homogenized and “safe”, horror movies will always have bite. Roeg’s The Witches is a premier gateway horror movie for younger audiences. – Charlie Riccardelli Cape Fear Makes It Your Damned Fault Some horror movies are about circumstances of pure chance; characters who find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. The most chilling horror movies, however, are about characters who are punished for the choices they make, who put themselves and their loved ones in terrible situations they can’t escape. Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear (1991) is about defense attorney Sam Bowden (Nick Nolte) who buries evidence that would acquit his client Max Cady (Robert De Niro) because he becomes so utterly appalled by his client’s sex crime. When Max is released from prison years later, he makes it his sole mission to harass and ultimately harm the attorney and his family. A remake of director J. Lee Thompson’s 1962 film starring Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum, Scorsese’s version is more successful because he’s not afraid of all the ambiguities. There’s complexity here. Max is at once menacing and charming, thoroughly terrifying as he seduces Sam’s wife and teenage daughter. Sam isn’t the type of victim we are used to seeing in horror films, either. He’s often selfish and cruel, making him unlikable and difficult to root for. It’s a delicate balancing act, and Scorsese pulls it off brilliantly, towing a line Thompson likely couldn’t have pulled off in 1962. Sooner or later, the choices we make catch up to us. Scorsese’s Cape Fear is a brutal reminder of just that. – Jon Lisi Scream Punishes Teenagers’ Impulse for Thrills An alternative title for Wes Craven‘s 1995 Scream might be Rules for Reviving a Genre. After a string of disappointing sequels and direct-to-video releases in the ’80s and early ’90s left many fans and critics believing the slasher film was as dead as its many victims, Craven’s Scream single-handedly revitalized the sub-genre. For the first time in a generation, a slasher film found new ways to be scary. Scream‘s fictional characters inhabit the same social and cultural space as the viewers (as it were), having seen the same slasher films that real-life viewers have. This was when a new era of pop culture savvy teens was arising, the early days of the internet and of “been there, seen that”. Scream‘s genre-adept protagonists cued in with that audience, uniting them in sheer terror by creating a meta-narrative that facilitated the all-important empathetic link between viewers and those imperiled, soon-to-be victims. This kind of self-awareness is key to this horror movie’s success. Craven blurs the line between fiction and reality, the characters’ world and the world of his intended audience, teenage moviegoers eager for a thrill. Audiences leave the theater imagining Scream‘s events unfolding in their own lives. This connection is an effective place for a horror movie to leave you. Fearing swimming in the ocean after watching Jaws isn’t quite as debilitating as not being able to trust your boyfriend after watching Scream. Who’s to say that another Billy Loomis (Skeet Ulrich) isn’t lurking behind those dashing brown eyes? Scream, like the best slasher films, is effective because it erodes our confidence in those around us and in civilized society itself. At a time when women are often being asked to rethink their perception of the seemingly good men in their lives, Scream‘s Billy Loomis may even find ways to be more effective today than he was in the 1990s. As psychopaths terrorize schools on a regular basis, Scream‘s depiction of Woodsboro High doesn’t seem so far-fetched. Indeed, “Ghostface” still lingers in the shadows, eroding our ability to trust in others. Everyone’s a suspect, and the best we can do – like Scream‘s terrorized victims – is learn the rules of the game and brace ourselves for when someone else comes along to rewrite them. – Jon Lisi Gone Girl‘s Horrific Blasphemy Leave it to David Fincher to turn a dissection of marriage and the media into lurid, provocative horror. Gillian Flynn successfully adapts her best-selling novel into a screenplay for Fincher’s Gone Girl (2014), and Rosamund Pike and Ben Affleck are pitch-perfect as Amy and Nick Dunne, a married couple with a few secrets, to say the least. Fincher doesn’t rely on gore to shock or scare the audience. Instead, he focuses on the story he’s telling, and all the sinister implications it holds about one of the world’s most revered institutions: marriage. Gone Girl is downright blasphemous with its bleak depiction of the “holy” institution. When Amy disappears mysteriously, Nick, the seemingly untrustworthy husband, becomes the main suspect. The twist: Amy has been alive all along; she escaped her marriage and framed Nick to make a point about the lack of freedom her marriage afforded her. What makes Gone Girl truly horrifying, then, is Amy’s calculated manipulation, the way in which she capitalizes on legitimate feminist ideas to become a kind of monster. In the age of #MeToo, the impact is disturbing and even dangerous. Amy turns herself into a domestic abuse victim and then lets Nick and the other men in her life carry the blame. It’s unclear why she does this. Perhaps she’s honest when she says she’s tired of being the “cool girl.” Perhaps she’s just a psychopath. Whatever the reason, the impact of her choices lingers long after the credits roll. We are left to wonder if there might be some Amys among us, plotting ways to turn the world against their loved ones. Do we ever really know someone? – Jon Lisi Editor’s note: This article was originally published on 29 October 2018.