Copyright scmp

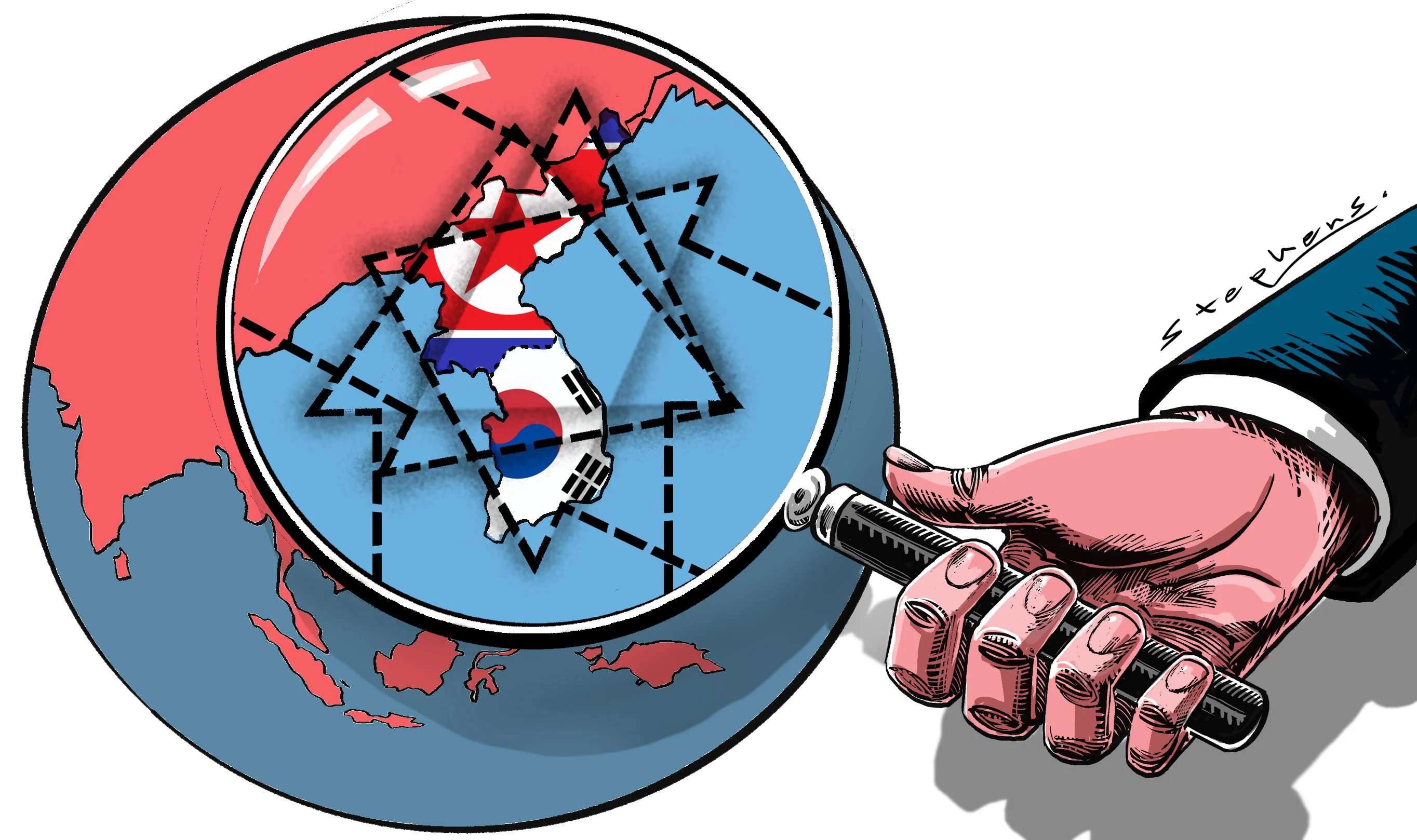

The Korean peninsula has snapped back into global focus. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Seoul is expected to bring the leaders of the US and China together for their first in-person meeting since US President Donald Trump’s second term began. Meanwhile, Russia-allied North Korea seeks US recognition of its status as a nuclear state and direct talks with Trump. This points to a structural shift in Northeast Asia’s security architecture. Rather than a simple US-China binary or a rigid two-camp confrontation, there are three overlapping triangles: the US-Japan-South Korea deterrence partnership, China-Japan-South Korea functional cooperation and a tightening China-Russia-North Korea counter-alignment. Their interaction makes the peninsula both a friction point and potential stabiliser. The last inclusive regional security framework, the Six-Party Talks, collapsed in the late 2000s, leaving a vacuum that flexible trilaterals have increasingly filled. “Triple trilateralism” has since emerged as a more adaptive structure that maps onto interlocked security, economic and ideological concerns. First is the US-Japan-South Korea cooperation, which gained momentum under former South Korean president Yoon Suk-yeol and is still robust operationally. This trilateral centres on extended nuclear deterrence and a coordinated military posture. It is driven by the urgency of North Korea’s advancing nuclear and conventional capabilities and its tightening ties with Russia and China. Since June 2024, the US, Japan and South Korea have conducted three iterations of the trilateral Freedom Edge exercise, alongside multiple bilateral drills. Missile-defence cooperation and real-time data-sharing complement this posture. Yet the alliance has internal strains. US talks with Tokyo and Seoul revealed friction over defence cost-sharing and trade practices. The election of Sanae Takaichi as Japan’s prime minister implies a rightward tilt on security – tougher on North Korea and China, tighter with Washington and Seoul – but her stances on history and territory could backfire with Seoul. Parallel to this is the China-Japan-South Korea trilateral, anchored in economic pragmatism rather than military calculus. Launched in 1999 on the sidelines of Asean+3, it has grown into a dense web of cooperation sustained by a leaders’ summit, a secretariat in Seoul and 21 minister-level mechanisms. Revived in May 2024 after a five-year hiatus, the ninth trilateral summit in Seoul recommitted the three countries to a regular summit and ministerial meetings and to functional, non-security cooperation. While this trilateral avoids hard security issues, it indirectly stabilises the region by deepening economic interdependence. With Japan holding the rotating chair, the test is whether the Takaichi government can turn this machinery into ballast – or whether domestic politics will clip its wings. The most geopolitically charged triangle is the China-Russia-North Korea alignment. Although it is not institutionalised, its tightening is visible in high-profile optics, notably at the September 3 military parade in Beijing, North Korea’s troop deployments supporting Russia in Ukraine, and the June 2024 North Korea-Russia mutual defence treaty. Beijing’s stance is nuanced. While it neither endorses North Korean deployments nor recognises its nuclear status, Beijing – Pyongyang’s economic lifeline, accounting for roughly 98 per cent of its foreign trade – has offered tacit tolerance, allowing Russia-North Korea cooperation as long as it does not destabilise the region or escalate to nuclear conflict. The peninsula is thus the physical and diplomatic convergence point of these dynamics. North Korea’s new satellite reconnaissance capabilities, upgraded missile platforms, deployment of Choe Hyon-class destroyers and covert nuclear-missile base near the Chinese border underscore a sustained military build-up. South Korea’s participation in US-led exercises and reliance on extended nuclear deterrence reflect deepening integration into allied strategy. North Korea’s diplomacy mirrors this geometry. It has rejected dialogue with Seoul, abandoned the goal of reunification and severed economic ties – partly in reaction to former president Yoon’s hostile policies. Yet Pyongyang remains conditionally open to talks with the United States, betting that tacit recognition as a nuclear state – akin to India or Israel – might one day open a path to normalisation. Cooperation with Russia delivers military and technological dividends and signals resilience to the international community. For South Korea, the strategic equation is complex. The Lee Jae-myung administration seeks a more conciliatory tone towards Pyongyang but remains constrained by security obligations inherited from the Yoon era. Seoul’s cautious approach to economic cooperation with Beijing and Tokyo reflects an effort to balance deep trade ties with China against security dependence on Washington. Triple trilateralism can have both stabilising and fragmenting effects. On the stabilising side, multiple communication channels and institutional mechanisms reduce the risk of miscalculation and provide platforms for crisis management. On the fragmenting side, divergent interests and asymmetries within and between groupings can produce diplomatic entrapment. US efforts to strengthen extended deterrence may heighten Russian and Chinese security concerns, prompting countermeasures. The geometry also sharpens questions about strategic autonomy. Japan and South Korea are pulled between deeper military integration with the US and continued economic interdependence with China. In its pivot to the Asia-Pacific, Russia must navigate reliance on Chinese infrastructure, logistics and diplomatic cover. North Korea, meanwhile, leverages its position to extract benefits from both Russia and China. The Korean peninsula is no longer merely a flashpoint; it is the axis around which the region’s trilateral geometries rotate. How these three triangles reinforce, offset or complicate one another will shape Northeast Asia’s future and broader strategic stability. The road ahead requires careful diplomacy, creative institutional design and recognition that no single triangle can monopolise outcomes. Managed with foresight, the convergence of interests and frictions on the peninsula could yield new multilateral avenues for managing tension; mishandled, it could again become a global fault line.