Copyright Deadline

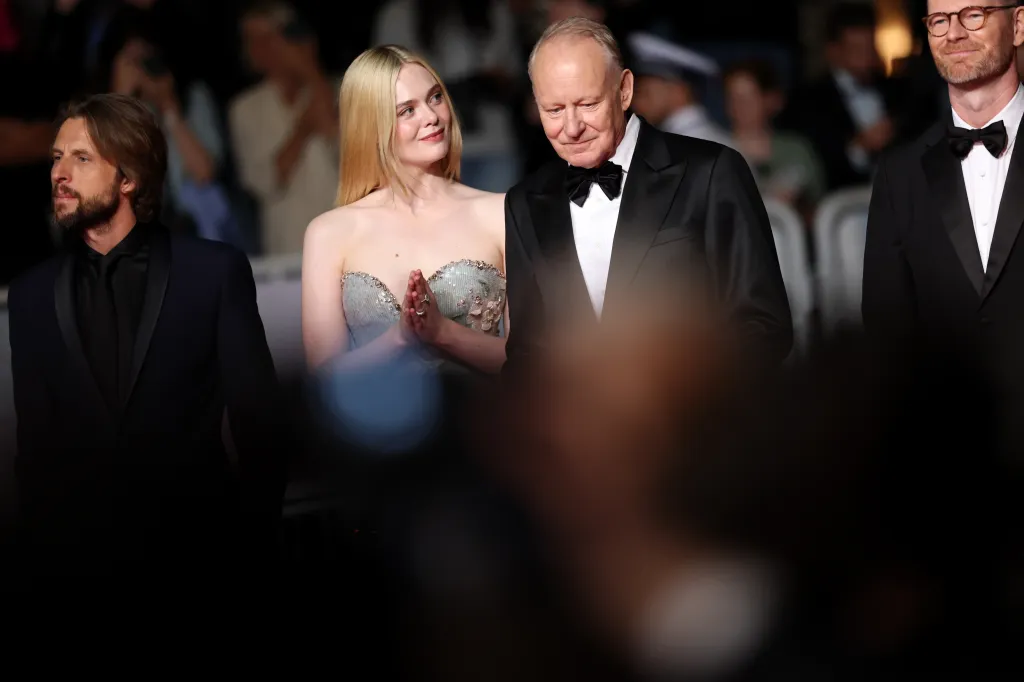

Few actors have had a career quite like Sweden’s Stellan Skarsgård, who became a big Scandi star in his late teens, blundered briefly into softcore porn, then nearly gave up TV and film altogether for theater. Something pulled him back, however, and the 74-year-old is now one of the most sought-after actors in the world, routinely popping up in mainstream Hollywood films, starting with 1990’s The Hunt for Red October. But, somehow, Skarsgård never sold out; it’s hard to believe that the same man who made six dark films with Danish enfant terrible Lars Von Trier also dad-danced in both of the Mamma Mia! movies. In Joachim Trier’s Cannes hit Sentimental Value, which won the festival’s Grand Prix, Skarsgård plays Gustav Borg, the estranged father of stage actress Nora (Renate Reinsve). Once a famous arthouse film director, Gustav has fallen into semi-obscurity, and suddenly comes back into Nora’s life with a highly personal project that he thinks will bring him back into the public eye. Co-written with Eskil Vogt, the psychological family drama that follows is Trier’s best yet, reuniting him with his Worst Person in the Worid star Reinsve and adding a powerhouse trio of performances by Skarsgård, plus Inga Ibsdottar Lilleaas as Nora’s sister Agnes and Elle Fanning as Rachel Kemp, an American actress being courted by Gustav in case Nora decides not to do it. In real life, Skarsgård is a rather more successful father; indeed, of his eight children, six have become actors too, the most famous being Alexander Skarsgård, who turned heads this year with the festival hit Pillion (proving that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree, Skarsgård Jr. played a charismatic leather-clad dom in Harry Lighton’s sexually explicit gay S&M love story). But even being a grandfather now hasn’t been enough to slow Skarsgård down, and the sheer diversity and quality of his work makes it all the more remarkable that — aside from a Golden Globe for HBO’s acclaimed mini-series Chernobyl (2019) and a Fangoria Chainsaw Award for the not-so-acclaimed Exorcist prequel Dominion — Skarsgård’s mantelpiece is remarkably light on gold statuettes. With any luck, Sentimental Value could be the film that changes that. DEADLINE: How did you get involved with Joachim Trier and Sentimental Value? STELLAN SKARSGÅRD: He called me. But I had been waiting for him to call — about anything — for quite a while. He called me and said he wanted to meet, in Stockholm, so I said, “Yeah.” I knew it was about his new film. I would have said yes immediately, of course. But we waited, and we walked around each other like two sniffing dogs, sniffing up each other’s asses. And then we had this meeting DEADLINE: How did it go? SKARSGÅRD: It was lovely. I’d never met him before. He’s such an endearing person, and beautifully intelligent too. So, we just talked in general and then I accepted the part. I would have signed on to anything, but that script was just so special. You remember the house in the film? One of the main roles is played by the house, And that was already in the script, it opened up the whole story to me. It was very playful, and very cinematic. it showed his approach to the subject matter, the kind of lightness that the film has. Even if it’s dark, sometimes. I mean, it deals with suicide, and big, serious problems like that, and does it seriously. But it maintains a lightness in it. DEADLINE: Joachim has been on American TV lately saying that he wanted you to play the character because he’s such an asshole, and audiences had to like him. SKARSGÅRD: [Laughs.] I warned him a little. I said, “Don’t make him a stupid asshole.” Because, of course, younger people, when they try to imagine an older man, they think they have problems bending down, that they have aching backs, that they don’t know how to handle a cell phone and stuff like that. [Being old] is not like that, so he took out all those sorts of funny quirks, because he wanted to make this man full, living human being. DEADLINE: What did you bring to the character? SKARSGÅRD: What I brought was life and nuance. That’s my only job. I want the director to have total control. And Joachim is like that; he has total control. Like all directors, he is very good when it comes to planning things. Everything is beautifully organized, and he casts the best people, not only in the main roles, but as runners and everything. Everybody is treated very well, everybody’s gentle on the set, and it’s a wonderful atmosphere. And then, on the set, on the days when we shoot, he leaves you alone. He doesn’t say much. Some takes are overactive, some takes are underactive; some takes you have a new idea, and you present that idea, and he lets you do it. And then he has full control over the toning of it, over choosing the takes. So, he creates the part, in a way, because, from the material he had, he could probably have cut together my character as a sort of maniac, crying, and screaming. But he tones it, and he does it very well. DEADLINE: Was it a help or a hindrance that the character was a movie director? Because you’ve obviously worked with a lot of movie directors. SKARSGÅRD: Yeah. Well, the first instinct was, of course, revenge. [Laughs.] But, no, it didn’t matter. I mean, it doesn’t really matter what kind of profession he has, if it’s a baker, or it’s a bus driver, or an actor. But what was important was that he was an artist, because the conflict for an artist is much harder than for anybody else, because his job is him. He can’t separate himself from his job. And combining that with being a present father, for instance, is very hard. I mean, you have to realize that if you sort of reduce the artist in you, you reduce yourself, and then you will become a different person, and maybe not as likable, and maybe your wife will divorce you. DEADLINE: You’ve been very vocal about some of your directors, including Ingmar Bergman. Did any such thoughts bubble up into this movie, or did you try to resist that? SKARSGÅRD: It was very easy to resist, because I didn’t care. I just wanted to make sure Gustav understood his work — his sensibility in his work is fantastic. He listens, and he can describe emotions beautifully. I wanted him to be that kind of director. But he is incapable of doing it in his personal life, because one’s personal life is much more complicated, and you don’t have the limits of an hour and a half screen time. You have an indefinite amount of complications. So, of course, most of us, in a way, flee from it to our arts. DEADLINE: Had you worked with Renate before? SKARSGÅRD: No, I hadn’t, but I really hope I work with her again. Every feeling, every nuance, it sort of shows in her face. Even if she blushes. She’s vibrant, full of life. So, it’s like looking at life’s origin, the fountain of life. And she is such a good actor. You feel like you’re in a jam session with her, because everything she does, you pick up, and everything you do, she picks up. And you start this dance, this jamming session, and it’s wonderful. I mean, every scene becomes much richer. But the thing is, in this film, it was about not having contact, not having a relationship. But we found a way, one that was very fruitful, to play it. We played it all the time. We had one scene where we had contact — we’re standing outside the window smoking, and we have no dialogue. But it worked. During those few seconds, you see the love between them. DEADLINE: Was it a hard character to get into? Because you have a very close connection with your children. How did you get into this headspace of a man who has no emotional contact with his children? SKARSGÅRD: Well, it wasn’t hard at all. I played my worst fears. And all those scenes where he’s really trying… I played him like he really wants to reach her and make contact with her. And you feel it, but he’s incapable of it. He’s stumbling. He’s very, very clumsy. And at the same time, he’s holding himself with this big posture and these big, big expressions. But he loses, and loses, and loses. Every scene with Renate, he loses. And it’s fun to play someone who’s not used to losing, who’s used to controlling even the minutiae of feelings, and he now can’t do it. It’s very common. DEADLINE: It must have been also very difficult for you to play somebody who’s out of favor, because you’re always working. But Gustav is a man whose career is on the skids and he’s trying to make a comeback. Again, how do you put yourself into that headspace? SKARSGÅRD: Well, since 1989, when I stopped at the Royal Dramatic Theatre, I’ve been working four months a year. I’ve been changing diapers eight months of the year, wiping asses and stuff, and doing homework. But you can’t do your art by yourself. You have to have other people to give you the part, or you have to form a theater company or whatever. When you haven’t worked for a while, even if it’s voluntary, you feel it comes creeping up on you. I mean, I’ve always had work. I’ve never worried about my future, but I’ve been worried about not working… I’m like, “Why can’t we start [shooting] today?” Because I need the stimulus I get from the set. DEADLINE: Why did you want to become an actor? SKARSGÅRD: I didn’t want to become an actor; I wanted to become a diplomat. DEADLINE: You could have been a good one! SKARSGÅRD: I started in theater and did a television series that became very famous when I was 16 years old. And even after that, I still didn’t want to become an actor, I wanted to become a diplomat. But, of course, that was a stupid idea, because being a diplomat is not what I thought it was. I thought it was someone who travels the world and creates peace. And most of them don’t. But, the theater, it’s addictive. And I became addicted to it. Or I mean, any kind of acting, any kind of expression. So, I just continued to work as an actor. I still haven’t decided what I should do when I grow up, but I’ll wait and see. DEADLINE: Your early film career is quite interesting. There are some racy titles in there. How did you get into movies? SKARSGÅRD: In a way, my first thing I was doing, as a child, was theater. And I did a TV series in Sweden called Bombi Bitt och jag, which was a sort of Swedish Huckleberry Finn. We had only one TV channel then, and so you became extremely famous overnight. And then I eventually quit school because I got offers from theater, and I worked in the theater for several years. I was very poor. The first sort of semi-pornographic film I got, Anita: Swedish Nymphet, was very innocent in a way. It’s not even a pornographic film. But it was a film that was being sold because it featured naked bodies, yes. I met the director in his library. He had a lot of books, and he talked about the importance of the material. He said, “It’s about a nymphomaniac, and it’s about what it means to be a nymphomaniac.” I was fine with that. I had no problems with sexuality, or nudity, or anything, because I had an extremely free upbringing. And also, I’m Swedish. [Laughs.] So that was not a problem. I was 20 years old, I think, and I really couldn’t believe that anybody would exploit somebody else’s nudity. That was a foreign concept for me. But anyway, I did that film, and I realized that maybe it wasn’t about the psychology of a young girl, it was about something more carnal than that. And I did a couple more. On the second one, it became really obvious, because the director wasn’t even pretending anymore. But he had a very nice house, and he held very nice dinners, so it wasn’t all bad. But eventually, I’d had enough of it. And I didn’t do any more films for a while. I think it was camera fright, in a way, but I can’t blame him for that. It was my own fault. So, I didn’t do film for several years. I worked in the theater all the time, but then eventually I went back. DEADLINE: Do you think your life would’ve turned out differently if you hadn’t met Lars Von Trier? Because Breaking the Waves seems to be a big watershed moment for you. SKARSGÅRD: Of course it would’ve been different. And especially because he’s lovely as a friend, and he’s fantastic as a director. He has revolutionized cinema, but he also revolutionized my life… When I talked earlier about acting, it is because of him. I’m drawn to lack of pressure, to freedom. And then I can go and play whatever I want. But, for me, the first thing I try to figure out is not what is my role, it’s who is the director? What does he want? Because when you do the kinds of films that I do, the arthouse films, it has to be the director’s film. Nobody else’s film. And he has to be as brave as possible, and he has to be as courageous as possible. Because all art of any importance, it has to have a sender. It has to be one person that does it. Or, like the brothers Dardenne, it could be two people. DEADLINE: Your career seemed to take off in the late ’90s. And you continue to be, as do your sons, in almost every film ever made. Were you aware of that, and how do you feel about the Hollywood movies that come your way? SKARSGÅRD: I feel good about them. I can’t think of any actor that’s had more fun than me. I mean, I’ve done the weirdest and darkest films, and I’ve done the lightest, and most soufflé, cake-y films. I vary my diet all the time. And I made a lot of films. I’ve been able to raise eight kids. DEADLINE: You went from Mamma Mia! to Nymphomaniac in the space of five years. You must be the only actor that has that kind of resumé, who can go from light to dark in such a way. SKARSGÅRD: It’s wonderful! DEADLINE: What is the film you mostly get recognized for? SKARSGÅRD: It depends on who I’m talking to. I talk to young and smaller girls, and it’s Mamma Mia!. And older girls, they’ve seen maybe River, a TV series I did for BBC. A lot of people mention, of course, the latest ones, and now it’s been Andor for a while. I’ve made so many films, and so many different films. I mean, I don’t think that anybody who’s gone to a cinema in the last 40 years has missed me. No matter what kind of films you like, I’m sure I’ve shown up somewhere. DEADLINE: You’ve made a lot of cutting-edge films, but this year it was your son Alexander who had a cutting-edge film in Cannes. How did you feel about Pillion? Did you feel like you were passing the torch? SKARSGÅRD: I couldn’t see it in Cannes, because I had too much to do, so I saw it in Telluride. It’s the only festival where you see films. So, I saw it there, and it was fantastic. It’s so lovely. And what I’m also very happy about is that Alexander is so free from the burden of conventions. He goes for the right things. He makes the right choices. DEADLINE: Are you still in touch with Lars Von Trier? Is there any chance of him working again? SKARSGÅRD: The last time I talked to him, he was doing a version of La Jetée, the silent film [by Chris Marker, 1962]. It was the same concept [using still images], because he thought he could do it at home. But since then he’s been much worse. I haven’t spoken to him directly, I’ve spoken through mediators, and I send him text messages now and then. Sometimes I get an answer, but it’s very brief. DEADLINE: What are you doing next? SKARSGÅRD: Well, as I said at the beginning, it’s very hard to find young people who can write parts for old people. So, I’m waiting for a role that is not crippled, that doesn’t have dementia, and that doesn’t have any problems at all with opening an email. DEADLINE: You’ve done a lot of fantasy movies lately, some Marvel, you did Dune. Does that appeal to your sense of play? Because one would imagine those films are pretty intense, and there’s not much freedom. SKARSGÅRD: I’m a big reader, but I’m not a big reader of fantasy or science fiction. But that’s because I don’t need the extra complications of [having to imagine] life on another planet, or another fantasy world. I mean, there’s brilliant stuff. Like 2001, that’s fantastic, of course. But because I’m an actor, I’m more interested in the micro, or in the big explosions of the human mind. DEADLINE: Obviously, you’re playing a director in Sentimental Value. Have you ever directed, or is it something you’d still like to do? SKARSGÅRD: No. Most actors, I think that we think that directors are more respected than actors, because they’re sort of “real” artists. They’re real artists because they can make the film from scratch and make it their own. But I did write a script, together with a friend, and we got it financed. Almost all of it was financed. And then it was taken over by a producer, a big producer in Sweden. Two years went by and nothing happened. And by then, I was so bored. I don’t have the stamina to be a director, actually. Or the conviction, or the manic side. DEADLINE: What was the film about? SKARSGÅRD: It’s a true story. It’s about a Russian balalaika player that is stranded in Sweden during the First World War, and he has an affair with, or rather falls in love with, a young girl. First, the girl falls in love with him, because she’s only 16, and he’s 35, and she falls in love with him like 16-year-old girls do. He’s not interested at the start but becomes infatuated with her. But by then, she’s lost interest in him, because a 16-year-old girl falls in love for two weeks and then it’s over. But the mother is now also infatuated with him, and so it’s a weird triangle. And they end up in a summer house on an island, where he goes crazy and kills the girl. There’s some good scenes in there, and it’s still a good story, but I haven’t opened the script in 20 years. DEADLINE: Would you have played the balalaika player? SKARSGÅRD: Yeah. I was young enough to star in it when I wrote it. DEADLINE: You made a very good point earlier. For a lot of people, the director gets much more respect than the actor. Has that been a source of annoyance to you in your career? SKARSGÅRD: No, and I think they deserve it somehow. I mean, it’s not easier, but they do create the film, and they should create the film, and the actors shouldn’t interfere. So, you’re a hired hand in a way. But I have a dream that, in a way, you can channel your view of humanity, or of the world, through the characters that you play. I don’t know if it’s true, but the self-obsessed artist in me imagines that. DEADLINE: Is there anyone you haven’t worked with that you’d like to? You’ve worked with some incredible people. SKARSGÅRD: Oh, there’s many, and some haven’t been born yet. I want to work with a lot of good directors, but, to me, the combination of director, material, the other actors, and even the crew is also important. I mean, I live on the set. I spend most of my time there. It has to be a pleasant place. And it has to be a place where I can feel creative and safe. DEADLINE: One last question. When you look back, how do you see the life you’ve led, in terms of your career?