Copyright scmp

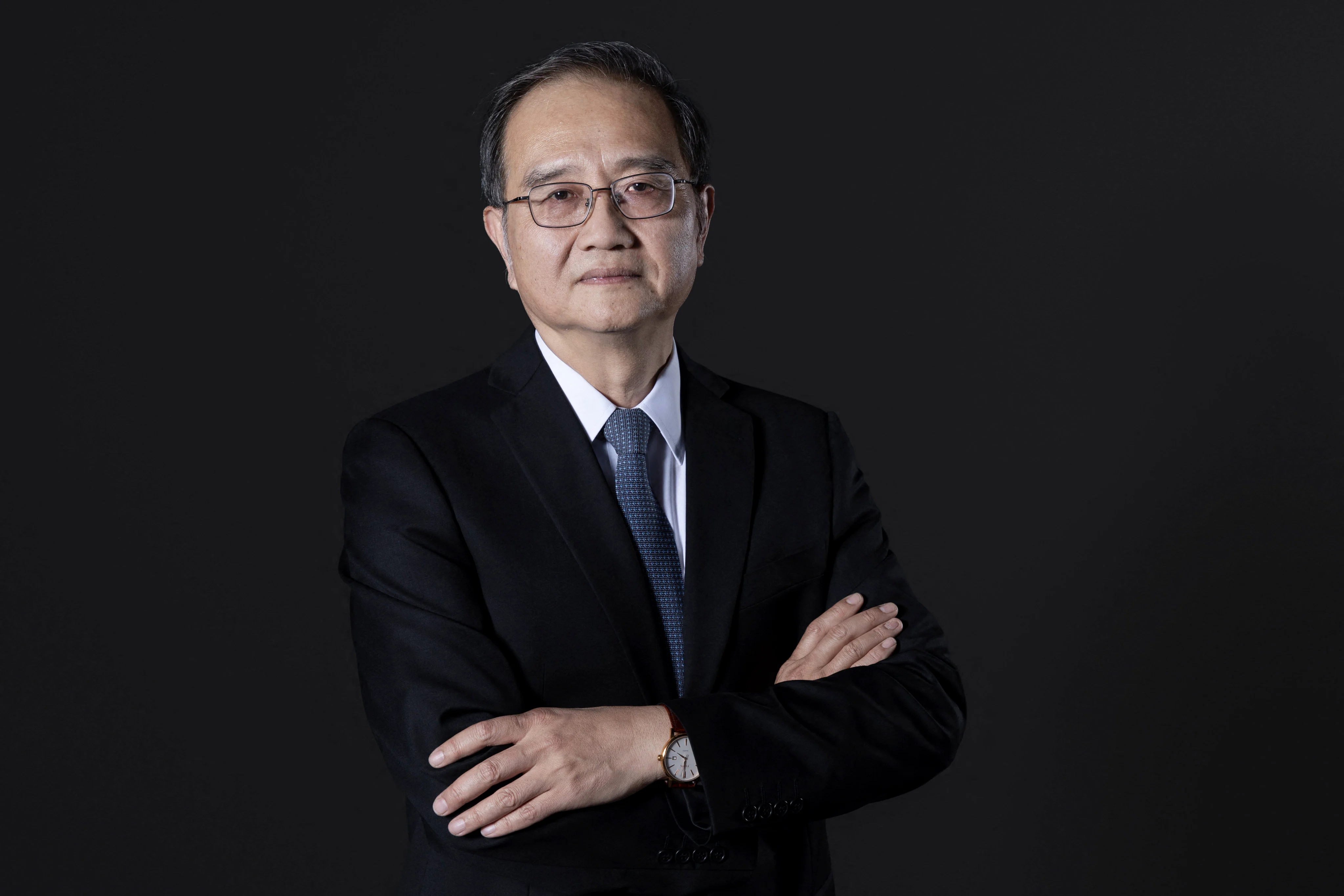

This month, the Post’s Xiaofei Xu sat down with Deng Li, China’s ambassador to France and Monaco, for an in-depth and wide-ranging interview. In part two, Deng discusses Beijing’s economic relationship with France and the EU. Part one can be found here. As Europe adapts to the changing nature of the global economy and the fast pace of technological innovation, China is ready to help the continent as it determines its role in emerging industries, Beijing’s top diplomat in Paris told the Post. “Many new industrial and supply chains are currently taking shape, continually emerging as technological revolutions advance,” said Deng Li, Chinese ambassador to France and Monaco, in Paris on October 15. “China sincerely hopes that these industrial chains will be global. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), especially those in Europe, must consider [their] place in the industries of the future.” China and Europe can both learn from each other, Deng said, adding that shared growth will ensure all can occupy a position in these supply chains. The ambassador said that protectionist methods are bound to provoke retaliation and will not help reduce trade deficits, naming the EU’s tariffs on Chinese-made electric vehicles (EVs) as an example. Measures like these, Deng said, will put Europe behind on bedrock technologies, eventually making cooperation more difficult due to an innovation gap. Instead, he added, Europe would be better off finding ways to expand its exports to China and reinforce their position in the Chinese market, to compete and cooperate there. “We are very open and willing to discuss this with them. China does not want to pursue a so-called trade surplus; it is completely unnecessary.” Purchases of hi-tech European products, such as the lithography machines used to produce advanced computer chips, would be one way to help balance trade, Deng said, also naming modern service industries as an area of opportunity for European companies in China over the next five years. Europe’s problem is rather a ‘defactoryisation’ – the loss of factories – instead of deindustrialisation Deng Li, Chinese ambassador to France Shipments of these items would be an ideal way to boost Europe’s export value to China given their high cost and complexity, Deng said, estimating the value of six lithography machines to be higher than that of the 1.15 million tons of pork the EU exported to China last year. Speaking on the recently concluded fourth plenum of the Communist Party’s Central Committee and the committee’s recommendations for the coming five-year plan, Deng said they present “significant new opportunities” for cooperation with France, and Europe at large. This type of trade is made difficult, however, by efforts from the United States to curb Beijing’s technological advancement, measures which have been far-reaching enough to constrain the activities of EU companies for fear of follow-on sanctions. The Dutch semiconductor giant ASML, for instance, has been required to apply for a licence before selling its most advanced lithography machines to China or servicing certain models that had already been shipped to Chinese buyers. European politicians and analysts have defended Brussels’ tariffs on Chinese imports as necessary actions to protect the continent’s industrial base and prevent further deindustrialisation. But in Deng’s view, the issue has been mischaracterised and the blame should not be laid at China’s feet. “Europe’s industrial groups are doing fine. They have gone global in the process of globalisation,” he said. “Europe’s problem is rather a ‘defactoryisation’ – the loss of factories – instead of deindustrialisation.” Deng reasoned that in today’s highly globalised economy, it makes little sense to criticise China for overcapacity, as its companies are both suppliers and customers. While some European carmakers might be worried about the rise of Chinese brands, he said, the continent’s parts suppliers are glad to receive the additional orders. “We should move beyond these traditional notions and try to understand that the modern economy is one of deep interconnection.” The ambassador said China bears no unique responsibility for Europe becoming a less profitable option for companies looking to set up factories; rather, he added, it is the nature of capital to move where investment is most efficient and where there is comparative advantage. “What Europe needs to do is figure out how to attract companies to invest and build plants locally. That is the question Europe should be asking, not blaming others.” Everything has its price, Deng said, and Europe should not look only at the negative side of globalisation while ignoring the vast wealth accumulated by European companies during the same period. According to Eurostat, the official statistical office of the EU, the bloc exported goods worth a total of €2.58 trillion (US$3 trillion) in 2024, making it the world’s No. 2 exporter of goods, second only to China. The same year, the EU registered a goods trade surplus of €146 billion, an increase of about €112 billion year on year. The 27-member bloc recorded a surplus every year between 2014 and 2024, with the exception of 2022. Smaller companies in developing countries suffered more than their peers in Europe during globalisation, Deng contended, adding that China was only able to get where it is today through heavy investment in education and hard work. “We absolutely must not forget that in the early stages of joining the tide of globalisation, we in China bore tremendous pressure and paid a heavy price.” Between 1998 and the first half of 2002, some 26 million workers were laid off from China’s state-owned enterprises, cutting the total labour force at these firms from roughly 75 million to 50 million, per a contemporaneous statement by Zhang Zuoyi, then the minister of labour and social security. “Progress cannot be stopped,” Deng said. “You might be able to hide from it for a while, but not forever. Rather than clinging to protectionism and increasingly falling into a passive position, it’s better to open up early, take proactive steps, seek cooperation and find solutions.” Speaking on China’s advancement in EV technology, Deng said Beijing is not opposed to technology transfers unless they fall under export controls or restrictions. But, he added, China cannot force its companies to transfer their most advanced technologies to their European peers. At the end of the day, the ambassador said, companies operating abroad decide what technologies they are willing to transfer, as European companies did decades ago when entering China. “My generation remembers very clearly how the level of those technology transfers evolved over time. The cars that first appeared in China were certainly not equipped with the latest generation of technology from Europe or the United States,” Deng said. Furthermore, the ambassador said, this quantum leap shows China’s rapid development in emerging industries like EVs and renewable energy cannot simply be credited to transfers of European technology. Above all, Deng said, China still has faith in Europe and values the continent as a partner, maintaining a willingness to work together wherever it can as the bloc figures out a way to organise its resources more effectively. “Europe has many strengths of its own, so there’s really no reason to be disheartened; it just needs to be more proactive and enterprising.”