Copyright Breaking Defense

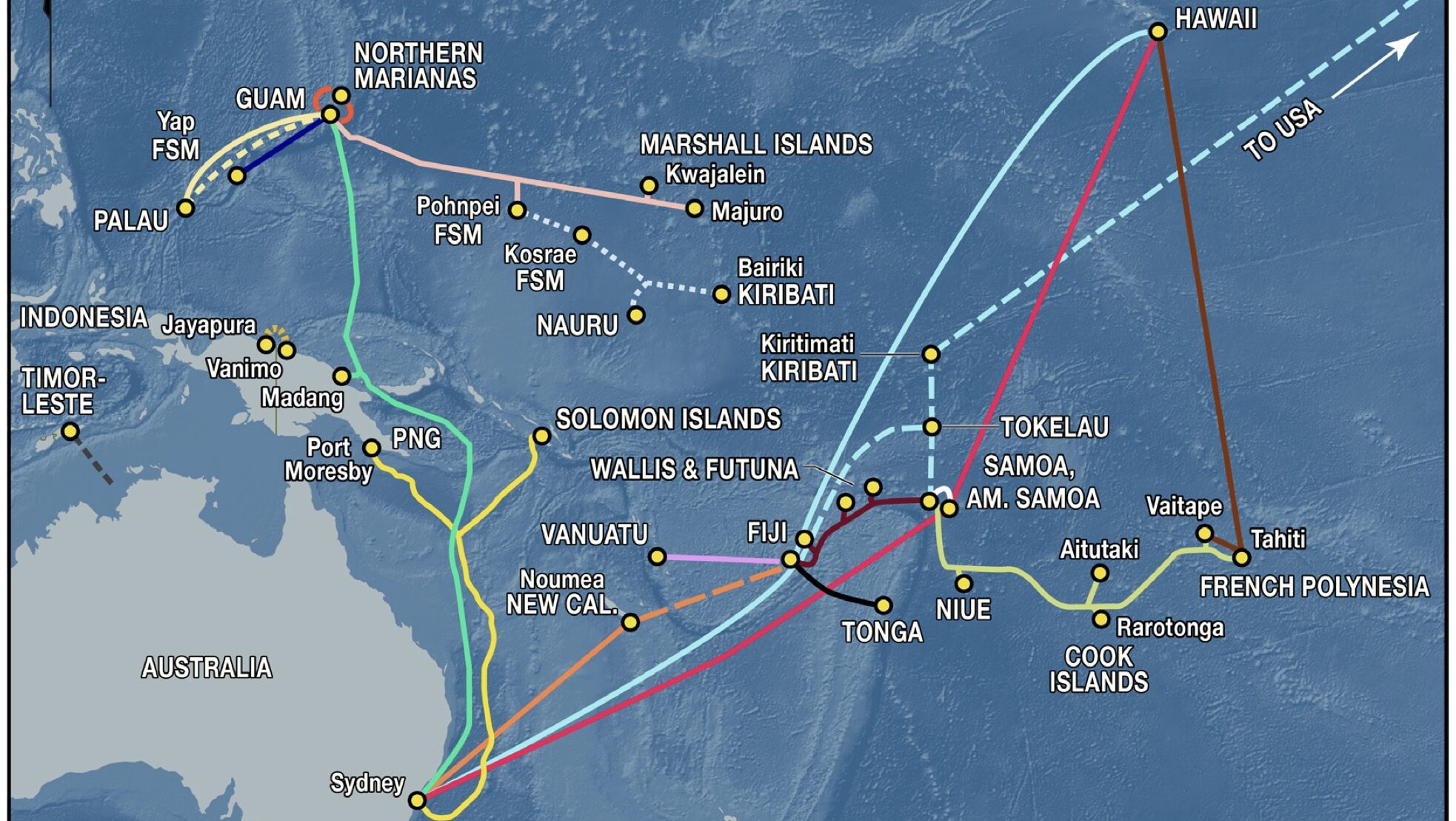

SYDNEY — The vast island continent here depends heavily for data and communications made possible by undersea cables, but Australia lacks the law, policy and capability to protect and repair the vital digital lifelines in the event of attack, experts here say. “Our connectivity to the global financial system and to family and friends across the world depends on the integrity of around 16 submarine cables that stretch across the seabed from continent to continent, and they plug in at various points along our coastline. This is what the sea means to Australia,” Chief of the Royal Australian Navy Vice Adm. Mark Hammond told this year’s Indo Pacific International Maritime Exposition at its opening ceremony. The stakes of failing to protect or quickly repair those cables are “existential,” the navy leader said. “The reality we face is that you do not need to invade Australia to defeat Australia. While maritime trade routes and seabed cables are our lifelines, they are also our greatest vulnerabilities. The loss of either would be an existential threat to our island and to our people.” OPINION: To protect undersea cables in the Middle East, US needs a new hub Yet three civilian experts — and several serving navy officers and commercial experts here — told a packed room that there is no single person or agency in the Australian government responsible for monitoring and responding to problems with those crucial cables. There is no doctrine for how to deal with attacks on those cables. And Australia lacks the commercial or military capabilities to respond quickly and effectively to protecting and restoring those cables. “We have no designated command. So who is responsible? Is it Navy? Is it Border Force? Is it Home Affairs? Who owns this mission? There is limited surveillance. So how do we monitor? How do we protect these zones?” asked Samuel Bashfield, a research fellow at La Trobe University. “Do we have the protocols for industry to request naval protection? And these aren’t just policy gaps, but I would say they’re operational vulnerabilities that adversaries can and will exploit.” David Brewster, senior research fellow at the National Security College of Australian National University, noted that Australia depends on foreign commercial companies based in Fiji — one week’s sail from the Lucky Country — to repair a cable. RELATED: First Ghost Shark Extra Large AUV delivered to Australian navy “Current repair arrangements are through a series of clubs, essentially geographic clubs, of private operators who band together and then hire a repair vessel to be on standby to repair cables. Now the prioritization of repairs is a matter for private operators, not for countries. So we don’t have a say,” Brewster said. And those measures are only designed to deal with relatively shallow, periodic and accidental cable breaks, not breaks that occur in different places and are below 200 meters or more. India is considering building a ship to repair cable, but it will cost up to $150 million AUD ($95 million USD) to build, he said, and Australia lacks the human capabilities needed to sail and run such a ship, so that is not a likely solution here. “Increasingly, our adversaries have technology to be able to attack cables down to much greater depth, say 2,000 to 3,000 meters, using submersibles, and there’s very little protection happening through at that depth,” he added. “We need to start looking at ways of imposing costs on adversaries who try and cut our cables. Now, the simplest way of doing that is tit for tat. So, you cut my cable. I’ll cut yours. Sounds easy, but, you know, one wonders how effective that will be, particularly when you’re dealing with countries who have less reliance on international cables that Australia does.” Breaking Defense asked the panel if deterrence by example might work, say by filming divers mining and destroying a cable and telling the world that if another country attacks our cable then this will be the response. “Yes,” Brewster said, “that’s a valuable signal. But we have to be careful about making those sorts of signals” noting the difficulty of attribution. He compared that to the sort of actions increasingly taken in the cyber domain, where countries increasingly band together to name an adversary. The importance of undersea cables is only going to grow as they are crucial to artificial intelligence networks, Bushfield said. The vulnerability of undersea cables for Australia is certainly not new. Sue Thompson, an associate professor at ANU’s National Security College said that the German military attacked communication cables that served Australia in the First World War and the Japanese ddi the same in the Second. Russia has repeatedly attacked cables in the Baltic over the last few years, several speakers noted. The Baltic incidents “really show that state actors are targeting submarine cable networks and that we should expect similar incidents in our part of the world, and that this is a defense mission, even though there might be some shirking of responsibility amongst Canberra’s agencies,” Bushfield said. “Naval protection isn’t just infrastructure policy, but it’s maritime security. It’s national security and it’s deterrence.” A Royal Australian Navy source, who asked not to be identified because he was not authorized to speak publicly, noted that the service has actually seen its acquisition and operations budgets shrink to some degree in recent years as pensions, medical costs and the AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine project have grown. While the service would take on the role of monitoring, defending and repairing cables if ordered, it would lack the resources to do much more than is already being done, the source said. And, as the experts noted, that is unlikely to be enough in time of war.