Copyright Los Angeles Times

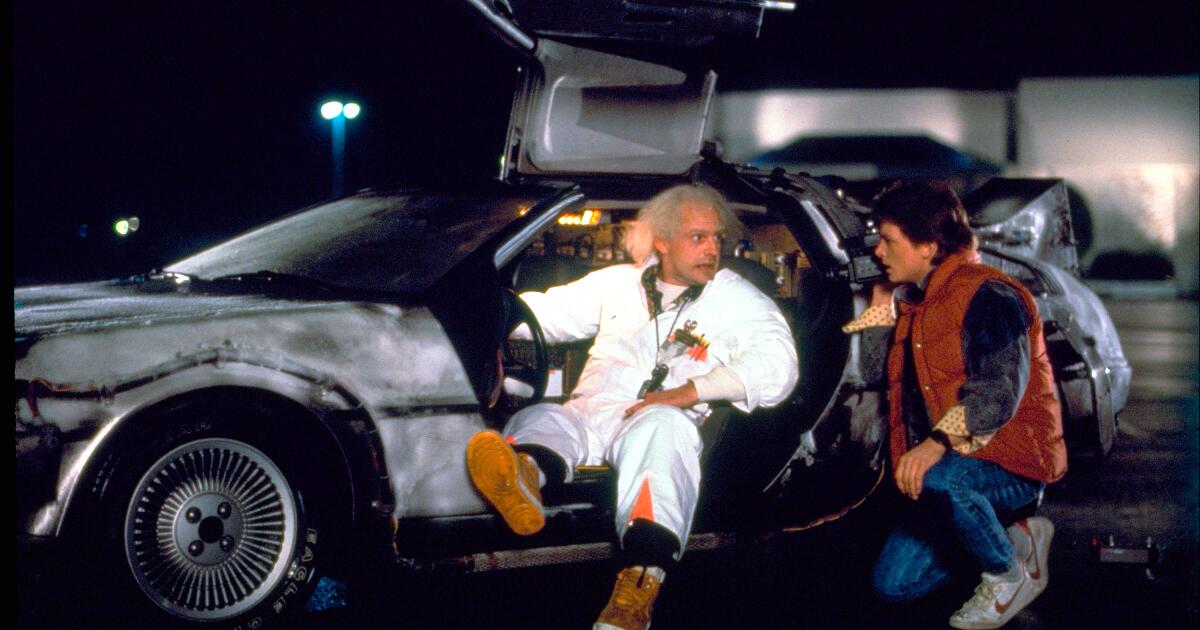

“Back to the Future” deserves to be endlessly rewound. Shot for shot, line for line, it’s the modern era’s zippiest comedy about the collapse of the American dream, with a sting that would have had its forefathers Frank Capra and Preston Sturges cheering: How the dickens did Robert Zemeckis get away with that? And I’m not even talking about the sequel where the bullying mogul Biff Tannen turns downtown Hill Valley into a hellish Pleasure Paradise Casino & Hotel. All of the franchise’s social satire is right there in the 1985 original, which returns to theaters this week to mark its 40th anniversary. “Back to the Future” just might be Hollywood’s richest, cleverest blockbuster — and its attention to detail deserves to be re-celebrated. Zemeckis, who co-wrote the screenplay with Bob Gale, must have been as much of a madman savant as Christopher Lloyd’s Doc Brown to compress so much plot into every frame. “Back to the Future” opens with a traveling shot of Doc’s garage apartment that tells the inventor’s entire riches-to-rags life story, from the incineration of the Brown family mansion to his decision to sell off his 435-acre inheritance to developers who behaved only a bit better than Biff, before the camera circles down to his humble twin bed littered with past due bills and garbage from the Burger King next door, serving Whoppers on what was once his front lawn. Squint and you’ll spot even more narrative set-up, including photos of Doc’s personal heroes, which pointedly include Benjamin Franklin, the harnesser of lightning. Then a radio clicks on, blaring a commercial for a downtown Toyota dealership that we’ll soon see once sold the American-made Studebaker. Then a TV news update about lost plutonium that concludes with the anchor parroting a fib from officials that the nuclear material wasn’t stolen by terrorists, but was simply an internal clerical error — a lie that gets exposed a minute later when Marty McFly’s skateboard rolls into its radioactive box. Next, Doc’s Rube Goldberg-ian breakfast contraption whirs to action with burned toast and a glop of overflowing dog food, implying that he and his dog Einstein have themselves been missing for a while. As a child, I misinterpreted that mess to mean Doc was a lousy engineer. Whoops! Plus, of course, we see the clocks. I couldn’t tell you how many. Four dozen? Six dozen? And half of them allude to the character beats ahead. There are cheap tickers jumbled with antiques that must have survived the house fire. Barometric pressure timepieces able to foresee an electrical storm. Decorative animatronic clocks like the one in which a ceramic wino swigs booze, just as Marty’s mother Lorraine (Lea Thompson) will chug in her sexy teen years and keep chugging until she’s a depressive, 40-something alcoholic. A miniature Harold Lloyd dangles from a pair of watch hands just as Doc will at the climax. And that’s merely “Back to the Future’s” first shot — a staggering pan with no cuts other than a quick close-up of Einstein’s food bowl right after the credits announce the name of the cinematographer, Dean Cundey, who was also responsible for one of the other signature single-take sequences of the late 20th century, the around-the-house, through-the-kitchen, up-the-stairs-and-back-down-to-the-yard Steadicam tracking shot of 6-year-old Michael Myers murdering his sister at the beginning of John Carpenter’s 1978 “Halloween.” Interestingly, Zemeckis and Gale hadn’t yet brainstormed that brilliant introduction when they began shooting “Back to the Future” with its original star, Eric Stoltz, playing the time-traveling teenager Marty McFly. The Doc Brown garage sequence doesn’t appear in the script until a draft dated February 1985, a month into re-shooting the movie with Michael J. Fox. Those improvements testify to the true mark of genius: the drive to hone something good until you’ve engineered something great. Of course, audiences don’t always know genius when they see it. They did with “Back to the Future,” which was the No. 1 film at the box office for 11 weeks. But Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” took nearly 30 years to go from flop to hit — 1947 wasn’t ready, but their kids loved it — and Capra himself was still alive that same summer of 1985 when the techno-innovator Ted Turner scooped up the rights to his classic and chucked it into the future by tinting it from black and white to color. “Even the villain looks pink and cheerful,” Capra complained to the press. “The story, therefore, has been changed.” Or, as Doc Brown might have yelped, changes could have disastrous consequences. Advancement isn’t linear or inevitable. Sometimes, as “Back to the Future” cynically implies, it backslides or gets stuck. Hill Valley Mayor Red Thomas blares the same verbatim reelection slogan in 1955 as Mayor Goldie Wilson does in 1985 — “Progress is his middle name” — yet the town is in visible decline. Marty comes of age in the Hill Valley of 1985, where vandals have shellacked the high school with so much graffiti that the janitors seem to have given up. The town square is in tatters: the store awnings are torn, the windows boarded up and the park paved over into a parking lot. What remains is a wasteland of pawn shops, porn shops, adult theaters, biker bars and, yes, that Toyota dealership, a pointed inclusion during the ’80s auto import war. Plus, the clock atop the courthouse hasn’t worked since that thunderstorm three decades ago. Not everything is the government’s fault. Mayor Goldie, having worked his way up the ladder from busboy to civic leader, is trying to fix that clock so his citizens can use it. I must have watched “Back to the Future” a dozen times before I realized that the gray-haired preservationist bugging Marty to save the clock tower from its Black mayor is advocating to keep it broken for the sake of Hill Valley’s “history and heritage.” Original script drafts were even bolder about portraying that activist, who Zemeckis and Gale described as a “church-group type woman,” a dangerously Dark Ages zealot. In a deleted line, she appears to believe that a lightning bolt destroyed the clock tower as a symbol of God’s will, gloating that the busted gears are a “landmark of scientific importance, attesting to the power of the Almighty.” Doc Brown would consider that blasphemy. Marty McFly gives her a quarter anyway. The kid doesn’t cross-examine his town’s decay. He’s always lived in Bedford Falls — er, Hill Valley — and while his puffy red vest gets him mistaken for a sailor, he behaves more like a frog in an already boiling pot. When Jimmy Stewart crash-landed in an alternative timeline, he was aghast at the economic disparity. But like an actual teenager, Marty is so obliviously preoccupied by his quest to get back to his pretty girlfriend that he makes it all the way to the end of the film without commenting on how bad he and the rest of his Pepsi Light generation have it. The film obliges Marty’s myopia, rarely zooming in on the ’80s rot, or for that matter, lingering on the benefits of the Eisenhower era when the middle class was booming, income inequality was shrinking and groups like the Kiwanis, the YWCA and Optimist International proudly slapped their emblems on the Welcome to Hill Valley greeting sign, pitching in together to build a better neighborhood. There are a few clues that this seeming stability has cracks. The casual racism and sexual harassment go beyond puerile Biff. Not only is it awful when Biff jams his meaty hands up Lorraine’s petticoat, but who the heck is that other dweeb fondling her on the Enchantment Under the Sea dance floor? Humming along under the surface are smaller signs of community breakdown, like when Lorraine’s father, Sam, rolls out a brand new TV set while the family eats dinner, thus curtailing chit-chat forever. A moment later, Sam scoffs incredulously at the idea that any household would ever be rich or bored enough to need two television sets. Zemeckis lets that line land like the punchline it is. But it’s also a test. Will Marty — will we — key into the bigger story underneath this adventure, the one in which the whole town, maybe the whole country, is going downhill faster than a speeding DeLorean? No matter how many times I re-watch “Back to the Future,” I find more touches to admire, more questions to mull. Marty spends a whole week flitting between the ’80s and the ’50s, never fully absorbing what the differences between those decades mean. Zemeckis hopes the audience will ask the follow-ups that Marty ignores. What happened to the four salaried employees manning the Texaco service station and why are his parents’ childhood homes nicer than his own? What would after-school dates with his girlfriend be like if, instead of awkwardly perching on a sidewalk bench, they could relax at a cheap and cheerful diner or a first-run movie house? Why shouldn’t their town square prioritize strolling couples and amateur oil painters and kids tossing softballs over parking meters and hatchbacks? Yet, when Marty zips back to 1985 to see a police helicopter circling overhead and the Essex marquee promoting the fictional porno “Orgy, American Style XXX,” the first thing he says is, “Everything looks great!” Actually, that’s not true. The very first thing he says is, “Fred, you look great!” to a homeless man napping under a pile of newspapers. Happy endings never felt so bleak. “Back to the Future’s” astonishing production design is by Lawrence G. Paull, who was 17 himself in 1955 — the same age as George McFly. Unlike Zemeckis (who was a toddler), Paull lived the exact arc of the film, coming to the project with a background in architecture that trained him to think holistically about fictional cities. Paull’s neo-futuristic visions of a 2019 Los Angeles had recently earned him an Oscar nomination for “Blade Runner,” justly applauded as a dystopian masterpiece. But I’d argue his subtler work on “Back to the Future” is as incisive and cutting, since it acknowledges that the dystopia is already here. Of course, Doc Brown never planned for anyone to go back to the past. He’d simply typed in the date he invented time travel for a few fleeting seconds of nostalgia, intending all the while to ditch his teen sidekick and zoom away to explore the 21st century. “I’ve always dreamed of seeing the future,” Doc says with glee, “Looking beyond my years, seeing the progress of mankind.” Nobody spoil what comes next.